Johann Sebastian Bach is not just big. He is the biggest. In every way, not just measured by greatness ... he’s got the numbers too.

Consider the announcement today from Universal Music Group labels Deutsche Grammophon and Decca:

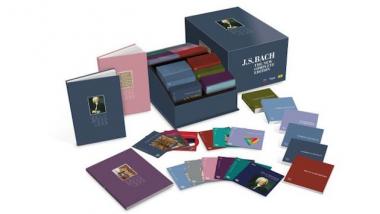

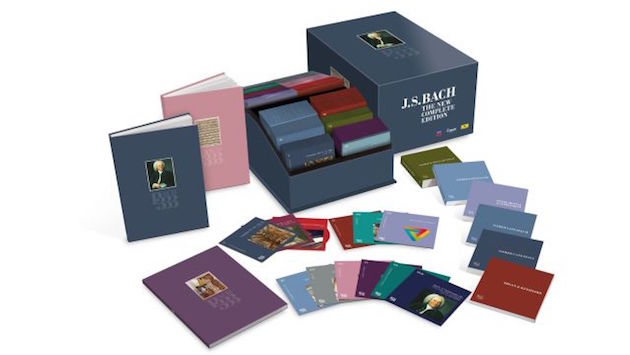

Marking Bach’s 333rd birthday (he was born in Eisenach, 1685), BACH 333 is the largest composer project in recording history and the biggest ever box set for a single composer. It’s 222 CDs, from 32 labels, with more than 750 performers, some 280 hours of music. Along with the size of the project goes the price, about $550.

The set also includes 10 hours of new and seven world premiere recordings. A DVD in the set is is a BBC film by John Eliot Gardiner, Bach: A Passionate Life.

“333” is more than just the number of years: in Bach’s music, there are many references to the number three, reflecting the important doctrine of Trinity or Tri-unity, which lies at the core of Bach’s Lutheran faith.

The publishers point out that the symbolism of three, representing the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, is everywhere in the collection of organ works Clavier-Übung III (1739). There are 27 pieces in the collection (3 x 3 x 3), perhaps representing the 27 books of the New Testament. The rather incongruous inclusion of the Four Duets BWV 802–805 which were probably not originally for organ, prompts speculation that they are mainly there to increase the total piece count to 27.

Publication coincides with the release of a new study conducted by Universal Music Group, revealing that performances of classical music are getting quicker. Evidence gathered from recordings within BACH 333 has found that performances of the same works of J.S. Bach have sped up considerably over the last 50 years.

Recordings of the same Bach work from different decades show that performances are getting shorter with the music played faster. Among the collection is a disc which features five performances of Bach’s Double Violin Concerto. The earliest of these recordings is from 1961 by David Oistrakh and Igor Oistrakh which lasts 17 minutes, a later recording from 1978 is just over 15 minutes, and the most recent recording from 2016 lasts around 12 minutes. That’s nearly five minutes quicker overall (a minute per decade) — an almost 30 percent reduction.

This evidence is further supported by the music scholar Nicholas Kenyon, who says: “We seem to prefer transparent, light, bright sound and it works with the work of many composers including Bach, Handel, and Mozart. It’s a basic change in taste from the rather weighty concert style of previous years towards something that is more light, airy, and flexible.”

Immediately after the announcement, Facebook and other social media virtually exploded with a debate over performance practices mentioned in the study, with posts such as:

A musical performance includes input from the performers, which is why “play it how it sounded in the composer’s day” is absurd. Glenn Gould demonstrated that you can make a convincing and satisfying interpretation of a Bach prelude and fugue at the extremes of tempi.

~~~~~~

And what if something didn’t sound so good in the composer’s day? Are we still bound to replicate it? Should we eschew technological improvements in instrument manufacture? I don’t quite get the craze (embraced by McGegan, by the way) for using valveless French horns, which are uneven — and even sometimes comic-sounding as the player is forced to bend the notes with the hand in the bell to take it beyond the bugle category.

~~~~~~

The modern performances that crack me up are the ones that are so incredibly fast that they require Baroque bows to do spiccato and Baroque oboes to double tongue.