With newly commissioned music sprouting all over the place during the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s epic centennial season, it seemed only fair to get jazz folk in on the act. In that spirit, the Phil’s creative chair for jazz, Herbie Hancock, curated an entire Green Umbrella program Tuesday night of six concert works — world premieres all — by composers usually associated with jazz.

Hancock dealt from the top of the deck, choosing some of the foremost names in progressive jazz and putting the LA Phil’s New Music Group and Chilean-born assistant conductor Paolo Bortolameolli at their service. The program was called “The Edge of Jazz,” yet what I heard in Walt Disney Concert Hall had only glancing contact at most with the sound and feeling of jazz, however wide that definition may be. This was concert music for a classical audience with not a rhythm section in sight. Nevertheless, with a little digging, one could ferret out a few connections.

Saxophonist Hitomi Oba — Berkeley-raised, now teaching at UCLA and Cal State L.A. — led off the evening with Aina for string quintet and tenor sax, whose spare, Webern-like opening and closing sections bookended a tortuously expressive middle section (with improvised sax solo) that seemed to channel Ornette Coleman’s symphony, Skies of America.

Two of the pieces were de facto concertos for piano and chamber orchestra. Billy Childs’s Of Darkness and Light began in anguish, gave way to a busy, urban-sounding stretch, followed by a lyrical intro to an elaborate, neo-Romantic, partly improvised piano cadenza (played by Childs) where one could detect a few jazz chords. About halfway through the first performance, the fire alarms in the hall brought matters to a sudden halt (a marijuana cigarette reportedly set it off), so everyone had to start over.

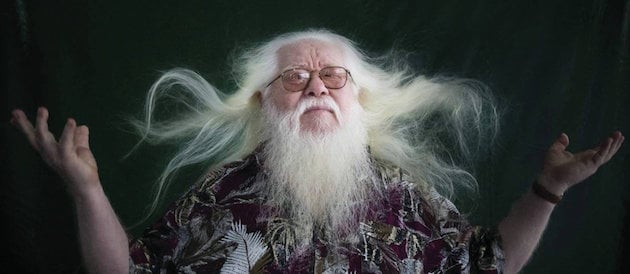

The other piano concerto was an orchestration of the unclassifiable Brazilian musician Hermeto Pascoal’s Suite Universal for chamber orchestra by one of his disciples, Jovino Santos Neto, who also manned the keyboard. This struck me as the most absorbing, wide-ranging piece of the night, moving through a series of impressionistic, lush, discordant, exotic modules with hints of Villa-Lobos and at last, a real Brazilian groove driven by a triangle just before the inevitable piano cadenza.

Vijay Iyer’s Crisis Modes had a three-part agenda — a call to action with attractive polytonal strings and a driving coda, a retreat to denial with delicate mallets and chimes in the night, and finally organizing an opposition movement as momentum gathered among the circulating strings. Fellow MacArthur Award recipient Tyshawn Sorey — also the drummer in Iyer’s jazz sextet — seemed to have Morton Feldman on his mind in his quietly spare, slow, delicate quartet for two mallet percussion players, viola, and piano. It even sported a Feldman-like title — For Fred Lerdahl.

Perhaps the most anticipated new piece was by jazz’s current man of the hour, L.A.’s Kamasi Washington (he is treated like a superstar in Japan), who burst into prominence with two massive, everything-but-the-kitchen-sink albums, The Epic and Heaven and Earth, within the last four years. Yet his Struggle From Within was the most conservative-sounding work on the program — tonal, mostly unison ensemble writing with a few playful solo melodies for flute and even the tuba — setting the all-embracing scope of his albums and EPs aside for now.

As an intermission diversion in BP Hall, the Phil’s recurring Fluxus celebration resurfaced with wild Up double bassist Maggie Hasspacher finding new ways to “play” her instrument as per Ben Patterson’s Variations for Double Bass (1962). Among the devices she used to produce sometimes excruciating sounds were two bows, a fan, a long plastic tube, and a section of cardboard. I dare say that this golden oldie from 57 years ago was further out on the edge — and definitely more amusing — than anything heard in the main hall.