Given a rainy Monday night in Los Angeles and a contemporary concert program, the curators of Monday Evening Concerts did something right because the house was packed and buzzing in Zipper Hall yesterday evening. That thing that they did right? Programming a Julius Eastman piece next to a recent work by Sarah Hennies.

The richness of the music outshone even the video mishap that resulted in Sarah Hennies’s Contralto having to be completely restarted. Contralto, written in 2016–17, is an incredible, hour-long work for video, strings, and percussion. The piece revolves around the term “contralto,” which describes the lowest range of the female singing voice. For a trans woman like Hennies, “contralto” presents an interesting envelope in which to think about trans-feminine voices, which, unlike those of trans-masculine people, are not affected by hormone therapy and remain lower. The video follows seven women of varying ages and personalities doing speech and singing exercises to develop cadence and tone that is more affirming of their identities.

Like a play, a large part of the experience was becoming invested in the women through their voices and unique responses to the exercises. Not to reduce real people to characters, but it would be hard not to feel that their personalities were integral to the piece after looking into their eyes for an hour. Hennies’s music sounded like a combination of mental chatter and visceral sensation. In waves, the percussionists skittered between light taps on a snare drum and ringing small handbells. The strings slid in pitch up and down past each other, arriving at chords stretched out like giant Alice in the rabbit’s house. One striking pairing of this music with the video was when the women seriously, if sheepishly, produced a nasal “EE,” the silliness of the sound paired with loud ringing of hand bells. The result was shimmering, endearing embarrassment.

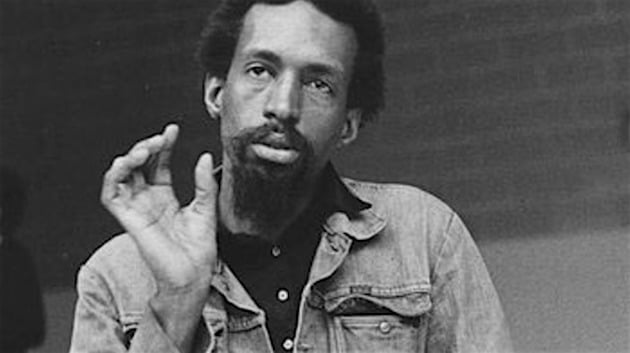

Contralto came after a riveting performance of Julius Eastman’s Gay Guerilla. Eastman was a composer active in the 1970s and ’80s in New York, and while he was a considerable force at the time, he died homeless and seemingly forgotten in 1990, many of his scores lost or thrown away. Renewed interest in reviving his work has led to performances like these, and it isn’t without a tinge of trying to make up for harm done. Gay Guerilla, a 30-minute work that flows like a muscle flexing and releasing, was played with ferocious love by pianists Todd Moellenberg, Brendan Nguyen, Adam Tendler, and Richard Valitutto. Beginning with light, layered, repeated notes, rising gently, the texture thickens as more notes are added in more insistent rhythms. At the highest wail of the piece, you could hear the bass strings of all the pianos buzzing and clacking together. The silence after the sound faded was deservedly long.

This concert was somewhat clumsily titled “The Gender of Sound,” and while Hennies’s piece clearly dealt with the topic, there was a weird conflation of gender and sexuality in the inclusion of Eastman’s Gay Guerilla (1979) under this umbrella. It was made clear that Eastman meant his piece as declaration of his will to put his life on the line for gay rights. Gender identity and the fight for gay rights are connected, but there was a more nuanced reason why these two pieces truly did make a great program together.

There is a dire need for art that paints marginalized people with a full depth of color and expression. These pieces did that, largely because the authors themselves are of those marginalized communities. Compassion is the unity that I sensed from the programming last night. I left the hall feeling that I had just heard the work of a man honoring himself deeply, and that of a woman considering herself and women like her to a degree that I have never seen on stage before.