We don’t see much of him around these parts, but the news that Akram Khan has delivered his last new solo work to the Bay Area before leaving the stage (in 2020) is something of a shock anyway.

Khan, British-born and of Bangladeshi descent, is among the most exciting of dance artists as a soloist and with his company, schooled in the ancient Kathak form as well as contemporary dance, both of which infuse his creations. Now he’s decided he can no longer move the way he used to — at 44, he’s done with that. And if we assume that he moves in all his works the way he does in the new Xenos, presented by Cal Performances Saturday night at Zellerbach Hall, we can certainly understand why. He is rarely offstage and rarely still; he is, in fact, spinning and jumping, drumming his feet and rolling on the floor and clambering uphill, only to collapse at its crest and slide down and rise once again.

At slightly more than one hour, Xenos (the word means stranger, outsider, and visitor) is a multipronged, painfully enlightening parable based in World War I, which saw the recruitment of more than a million Indians, mostly poor peasants, to the British Indian army. Many of the sepoy, or Indian infantry, were maimed and many died; for others, the war was relived in flashbacks for the rest of their lives.

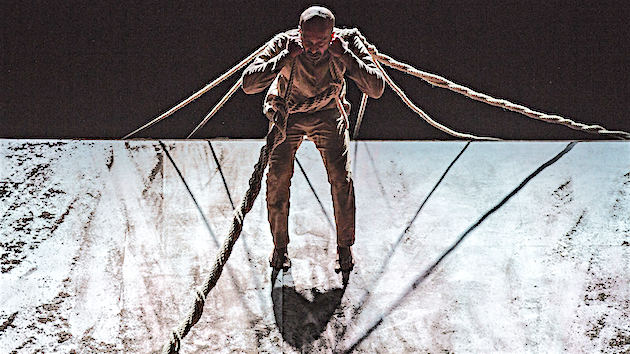

The audience enters to see a singer and a musician on stage as entertainers at a typical Indian celebration, with hanging lights and assorted seating and a carpet, with ropes lying on it, stretching up a hill. When Khan arrives, he simply noisily drops in, landing with a thick rope in his arms. He’s dressed in Indian white pajamas and performs as a Kathak dancer, bells around his ankles ringing as he steps and twirls and lands on a bench that ominously breaks beneath his weight. Suddenly, there’s a crackle of static. Everything — lights, furniture, carpet, tables — is pulled uphill, disappearing over the crest, by those ropes as Khan futilely scrambles to hold onto them and the normalcy they symbolize.

Blackout. Narrative, delivered through the horn of a gramophone: “You think that this is war? This is not war. This is the end of the world.” The ensuing set, designed by Mirella Weingarten, is amazing; that hill, for the duration of Xenos, becomes war-torn earth — we can smell it periodically — foxholes, and alien terrain. The lighting, ochre or brown or cold blue or gray, suggests varying degrees of apocalypse, never as strongly as at the end, when hundreds of rocks at the hilltop roll down, suggesting an avalanche of dead bodies. The surrounding music, by frequent Khan collaborator Vincenzo Lamagna, hauntingly blends acoustic and electronica.

The gramophone at one side of the stage takes on powerful dimensions as Greek chorus—augmented several times by a mourning, haunting quintet of singers and musicians in white robes, standing at the crest of the hill. The gramophone’s bell is also the source of an old World War I pop song and serves sneakily as a spotlight container (the bright orange light is inside the large bell, which turns of its own accord to face (balefully, it would seem) the audience. Its chief raison d’etre, though, is to emanate chaotic static, often preceding a loud explosive drumbeat.

From my seat in the audience, I could barely hear under fire what the gramophone was saying, but it didn’t seem to matter. Kahn mutely said it all, furiously scrambling as a human under attack or as a soldier on post, then collapsing in agony, tearing off his shirt as he tried to breathe, to little effect. His arms stretched and writhing as a bird’s might (the myth of Prometheus, pinned down and under daily attack by a bird of prey that ate his liver only to reappear the next day and eat it again), his body contorting and torqueing, his moments of lying prone and nearly still trying to recover, repeated themselves over and over again.

Xenos could have used a little editing. Even so, the suffering of the stranger could have been that of anyone, in war or in a time of deceptive peace, anywhere in the world in 1913 or today. Xenos is universal, unforgiving, and unforgettable.