There are too many Anthony Davises in the headlines this June. On the same day (June 15) when it became known that the Los Angeles Lakers were about to trade a whole bunch of players and draft picks for Anthony Davis the basketball star, Anthony Davis the composer unveiled his provocative new opera, The Central Park Five, in the old Warner Grand Theater in San Pedro near the L.A. harbor. The opera won’t get him a lucrative new line of sneakers, but it will forcefully remind audiences that racial profiling and coerced confessions remain a blot on the American justice system.

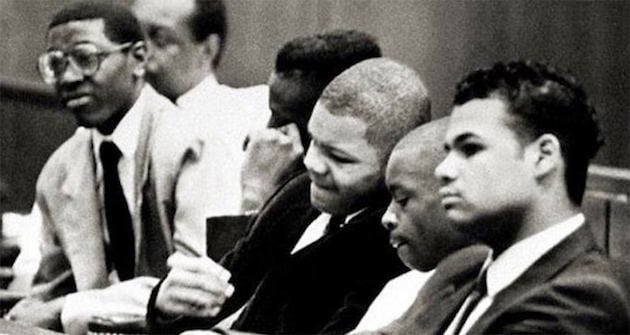

The Central Park Five, which tells the story of five teenagers who were falsely arrested and convicted of the rape and mutilation of a 28-year-old woman jogging in New York City’s Central Park in 1989, started life in a partial workshop version called Five that was presented in Newark three days after the 2016 presidential election. In a pre-performance talk, Davis said that the present version is “monumentally” changed from the first version. For one thing, it did not include the character of a New York real estate developer who placed ads in New York’s four leading newspapers before the trial calling for the death penalty for the five teenagers, four of them black, one a Latino.

But the election got Davis to thinking that this incident was the real start of Donald J. Trump’s career as a politician, fanning the flames of race hatred as a way of getting attention. So he inserted the then-43-year-old businessman into the opera as a reminder of “how we got to where we are, and how dangerous it is.”

Never an outfit to shrink from a touchy topic, Long Beach Opera presented The Central Park Five as a hard-hitting, straight-forward narrative, without poetic abstractions or doppelgangers doubling the characters or other tics that today’s new operas tend to overuse. Richard Wesley’s libretto stuck to the historical record and stage director Andreas Mitisek, LBO’s multitasking artistic and general director, made economical use of a collection of walls and doors on casters that also served as screens for projections of period headlines and photos.

In his operas, Davis has leaned one way or another between his two bases in the classical and jazz camps, but in The Central Park Five, he balances both with seamless ease, with electronic interjections from the sound booth between some scenes. Acerbic classical passages alternate and even coexist with a jazz rhythm section, swinging brass riffs enliven some of the interludes, and some of the harmonic colors summon the ghosts of Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus. Davis claimed his score contains influences of 1989 music like Take 6‘s contributions to Quincy Jones’s Back On The Block album or Tone Loc’s “Wild Thing,” but they are difficult to detect. The music could be particularly creepy, atonal, and above all, relentless when the five teenagers were being subjected to physical and psychological intimidation by the New York police department. It’s a very interesting mix as befits a composer who also has made a strong imprint in the jazz world as a pianist and the LBO pit band, under the direction of Leslie Dunner, was able to get wholeheartedly into the groove when needed.

Would that the sung lines were as interesting as the instrumental music underneath, but it’s just tuneless recitative broken up by ensembles for the Five, standard stuff for contemporary opera. There is very little individual character development to set the five teenagers apart; rather, they are depicted as a team of scared kids caught in a racist trap (none of the real-life Five knew each other before being arrested), wanting to go home.

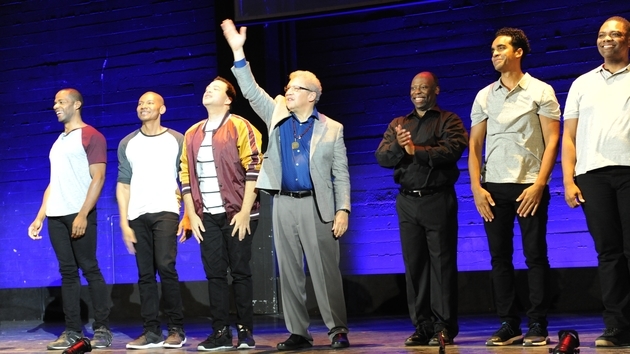

The Five were: Derrell Acon (Antron McCray), Cedric Berry (Yusef Salaam), Orson Van Gay (Raymond Santana), Nathan Granner (Korey Wise), and Bernard Holcomb (Kevin Richardson) and all sang well separately and in ensemble. Zeffin Quinn Hollis played a composite character called The Masque, spouting white supremacist slogans and slipping into the roles of police interrogator, news reporter, and such.

Then there was Thomas Segen’s spot-on impersonation of Trump, preening before the CNN interviewer, wearing the usual too-long red tie, making the all-too-familiar hand gestures and self-satisfied poses with jaw jutting out. Yes, he is a tenor, the closest voice match to the real-life figure. The most controversial part of the portrait — or it certainly will be for Republicans — is the Act II scene in which he is dictating orders on the telephone while seated on the toilet somewhere in the Trump Tower.

You can laugh, and many in the room did, but this guy became the 45th president and as of 2016, despite the exoneration of the boys and a confession by the real rapist, all backed up by DNA tests, Trump still thought that the Central Park Five were guilty as charged. That and the never-ending epidemic of racial profiling in America means that The Central Park Five may be a pertinently powerful piece of music theatre for quite a while. No word yet as to where it will play next, but it should.