He once played Curly in Los Angeles Opera’s 1990 production of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma — making his entrance on a horse! Indelible moments have been many for baritone Rod Gilfry, who began his affiliation with LA Opera in 1986 in a production of Otello, singing a solitary line in the Verdi tragedy. The Southern California native who earned a bachelor’s degree from California State University Fullerton and a master’s degree from the University of Southern California has some 77 operatic roles to his credit.

A renowned Mozart specialist, Gilfry, who was born in 1959, has sung the titular role in Don Giovanni and Papageno in The Magic Flute, for LA Opera. He’s also been featured in a number of other productions with that organization, including a triumphant Billy Budd in 2000.

Along the way, the commanding baritone has also performed cabaret, with a new show being performed at Pasadena’s Boston Court Oct. 18, while his success in new music has prompted The New York Times’ Anthony Tommasini to write that Gilfry is “becoming the singer of choice for new American operas.”

Indeed, shooting to fame at the San Francisco Opera in the role of Stanley Kowalski in the 1998 premiere of André Previn’s A Streetcar Named Desire — opposite Renée Fleming — Gilfry has gone on to originate an array of portrayals, including the role of Mr. Potter in Jake Heggie’s It’s a Wonderful Life in 2016. He also sang the role of Walt Whitman in Matthew Aucoin’s 2015 opera, Crossing. SFCV’s reviewer was particularly impressed with Gilfry’s tour-de-force performance in David Lang’s the loser for LAO.

And their collaboration continues in February, 2020, when Gilfry takes on the role of the father in Aucoin’s Eurydice, a co-production with the Metropolitan Opera featuring a libretto by acclaimed playwright Sarah Ruhl.

I caught up with Gilfry by phone in between his teaching gig at USC, a position he’s held for 11 years, and working on his cabaret performance with Christopher Denny, his accompanist of some two decades.

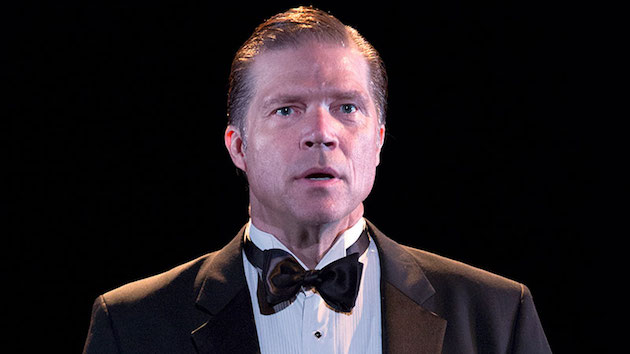

What is the appeal of cabaret for you and what can audiences expect — will you be doing patter and wearing a tux?

I will not be wearing a tux and there will be patter. I probably talk too much, I usually do, but it’s all carefully planned in advance — the order of songs, how they link together, how they [relate to] aspects of my life. It’s important for me to do a show that’s truthful and honest. I can’t do a show about cavorting with lots of women — I never did that. My life is about my marriage of 39 years — our kids, our four grandkids, my career, the different places we’ve been, the different experiences.

It’s family-oriented and romantic, but with enough funny, sort of compelling and exciting songs, too. I think it’ll make a good show. We had 65 song possibilities and settled on 17 songs that go through a journey. There’s a section about traveling, hoping to do well in whatever job, being lonely, my wife being lonely, then coming together.

We have Sondheim, a few songs by Irving Berlin, Bernstein, and there’s a good dose of Cole Porter. I’m also doing two numbers with guitar — acoustic and electric. I’ve played guitar since I was 11, but the way I play you wouldn’t know it. When we decided to do this, I hadn’t picked up the guitar for three years. I’ve been trying to get my fingers tough again.

Do audiences for cabaret differ from those attending opera?

It’s hard to know, because you don’t know who is in the audience with opera, but a big proportion of people who know me from opera come to see me playing myself instead of playing a character. That’s one thing I love about cabaret; the concept is that you’re yourself. You talk to the audience — it’s a wonderful thing and much more intimate. You can also change it up as you go along, which is really fun. It’s like walking a tightrope of sorts [but] I enjoy giving all of myself, my full voice.

Speaking of playing a character, do you have a favorite role in opera and what classical role would you like to do that you haven’t yet?

I have a favorite and it’s Billy Budd. I haven’t sung it since [2000 because] some manager told me that I needed to give up Budd. He said you’ve got to move on to more dramatic repertory and I never took another Budd. I’ve had plenty of offers and it’s the closest to my heart. It’s a real masterpiece and I felt so at home in that role. It’s probably my favorite still [but] I’m hoping to do my first Germont in La traviata and Scarpia in Tosca.

What is your attraction to new music, having created a dozen leading roles in world-premiere works, and how much are you involved with the composer?

It depends on the composer. Some like to write their baby and say, “Here’s the baby, don’t tell me anything’s wrong with it.” Matthew Aucoin is extremely collaborative [and] he’s been a joy to work with. Jake Heggie — you get together and you do workshops and go through it. “Is that too low, too high, is it a good part of your voice?” It’s tailor-made for me.

The attraction is that I find it very challenging. After I did Streetcar, I became known as the guy who could pull off a new role like that — when composers wrote stuff with me in mind. They say, “I want you to do this new opera.” This looks good and you end up doing it. It’s become my bread and butter. There continues to be, not only new operas, I also have some interest from an opera house in Italy of me doing the title role in Lear by [Aribert] Reimann [premiered 1978].

I’m interested in a big challenge. When I was asked to do Saint François d’Assise in Amsterdam, it’s 5-1/2 hours long and is hard to learn and memorize, but I thought I would like to try that. So I did. You never know. I believe you have to take risks in order to grow. I’ve fallen on my face a few times and I’m still healthy — it’s the experience of trying. I can [also] tell if it’s not going to work — if it’s ridiculously difficult. I’ve got a good sense of that now.

As you know, Martin Bernheimer died recently. In 1994 he wrote of your Don Giovanni, “This is an extraordinarily talented young man blessed with a real flair for the stage, a sophisticated sense of style and appealing vocal resources. Gilfry, moreover, is an artist who actually can exude charm without being arch about it.”

I totally forgot about that one. It’s so wonderful to be recognized like that. I always read something from reviews — even bad ones will tell you something. I know how I did. I know a reviewer points out that I made a mistake and he says this or that. I know better — they just didn’t get it. When you get a review like that — that’s so affirmative — it’s really nice and I always hope that I could express emotion without seeming arch about it. One of my big goals is to communicate truthfully. I want to be a good storyteller; I want people to feel it’s honest and direct.

What conductors would you like to work with and what opera houses would you like to play that you haven’t?

I’d love to do Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires. My teacher Martial Singher sang there and said it was the most wonderful opera house he ever sung in. Just for that nostalgic element of it, it would be fun. I’m sort of over being excited traveling somewhere, [because] travel’s a bitch, even if you go first class — those long plane rides, jet lag, setting up shop in a new town. I’ll keep doing it as long as I can, but I’m happy in Southern California.

This is a beautiful place and I don’t feel like I’m settling, but feel like I’ve been there and done that. I also want to be selective. Working with Renée’s been great and she pointed out that we seem to have a similar approach to singing and technique. Listening to her sing and working with her, it’s probably true. I feel there’s a real collaboration [like] when you’re playing tennis, you have to field the other person’s shot. I feel there’s that back-and-forth kind of collaboration.

Have you noticed the audiences for opera are changing — either getting younger or dying off?

The audiences are slowly becoming younger. [Yuval Sharon’s] The Industry — they’re doing amazing work in getting younger audiences interested. It’s a great model of doing new works that are intriguing; it’s not run of the mill. Beth Morrison is at the forefront in American opera, producing these things that are so compelling, like David Lang’s previous opera, Anatomy Theater. She’s the kind of person we need now to get younger audiences coming in. She’s had quite a bit of success and LA Opera is being so innovative by collaborating with her. It’s a really great sign for the future.

Where do you see yourself in five or 10 years?

I see myself continuing with what I’m doing in terms of operas and new works. I see myself adding new roles to my repertory that I can identify with and are age-appropriate — and challenging. I hope to continue the cabaret stuff. I have to say that I feel like I’m singing better than I ever have in my life and I think it’s largely because of my teaching at USC. It’s not just about me imparting my knowledge to a student, it’s about figuring out what I know and how I do what I do.

I’ve been coming to the realization that what I think I’m doing technically is that I’m doing it differently and taking that discovery to learn how can I do this even better. I’m discovering what the real elements of my signing technique are. My voice is changing and I’m imparting this to my students who teach me so much largely through their inability to do what I’m asking them to do. My first year of teaching I thought this is going to be easy but you have to break it down into little constituent parts and figure it all out. Being a good teacher is communicating with a student on the level they’re at. They don’t understand that they have to be really concentrated, that they have to practice, undoing some kind of tension they have and it takes daily practice and they have to be super prepared.

When you first began singing it was under the name Rodney Gilfry. What prompted you to change it to Rod?

The short answer is that my mom told me she had a boyfriend in high school who had wet lips and was named Rodney, so I kept on thinking about that. After “Streetcar” I got an agent for theater and TV and I said, “What do you think about my shortening name to Rod?” They thought it was a good move — that it was more rugged. But it’s made no difference at all.