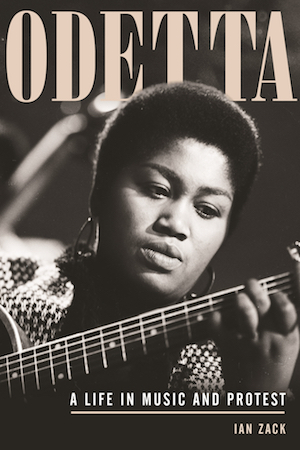

Writer Ian Zack’s engaging, well-researched biography, Odetta: A Life in Music and Protest (Beacon Press), brings forth a most remarkable, regrettable truth: The unorthodox hairdo and physical dimensions of one of the most influential 20th-century American folk singers received nearly as much critical attention during her lifetime as did her impressive voice and vital role in African Americans’ fight for civil rights.

Born in widely segregated Birmingham, Alabama, contralto/guitarist Odetta Holmes (1930 – 2008) moved as young girl with her family to Los Angeles. At age 13, she began voice training, singing German lieder and art songs in private opera lessons and performing in choirs and theater ensembles.

Born in widely segregated Birmingham, Alabama, contralto/guitarist Odetta Holmes (1930 – 2008) moved as young girl with her family to Los Angeles. At age 13, she began voice training, singing German lieder and art songs in private opera lessons and performing in choirs and theater ensembles.

As a young adult during the folk music revival of the mid-1950s and ’60s, she began a career that had her performing in San Francisco at the War Memorial Opera House and clubs like the Tin Angel on the Embarcadero. Appearing on the East Coast in New York City nightclubs and on tour in venues worldwide, Odetta’s concerts were a hybrid blend of folk tunes, spirituals, chain gang work songs, children’s music, and jazz standards. The jazz was more successfully rendered in her later years, when her smooth contralto voice weathered and her onstage anxiety was ground down by a life of hard blows.

Zack’s compelling biography traces the wax and wane of Odetta’s career that had her at the high points performing on prime-time television as a featured star in friend and admirer Harry Belafonte’s groundbreaking specials, and singing in support of the civil-rights movement at the 1963 March on Washington and the Selma-to-Montgomery march. The appearances earned for Odetta the titles “Queen of Folk” and “The Voice of the Civil Rights Movement.” A regrettable sign of an overtly racist, sexist society, she received significant mention in the press regarding the unironed, short, kinky afro she sported and about her generous girth.

Fortunately, in hundreds of interviews, testimonies, quoted reviews, and specifics drawn from Odetta’s seminal recordings (Odetta Sings Ballads and Odetta at the Gate of Horn, among others), Zack sticks to higher ground. His subject’s tremendous influence and importance in music history are obvious in words spoken or written by generation-spanning artists including Bob Dylan, Carly Simon, Joan Baez, Tracy Chapman, Rhiannon Giddens, Miley Cyrus, and more. Belafonte favorably compared her voice to that of orator and bass-baritone singer Paul Robeson and said, “Her voice is enormous. And the depth and range of it is never-ending.” About her physical appearance, Belafonte told CBS executives, “She’s a Nubian Queen. She is the mother of history, of all of Africa.”

As a political activist, Odetta channeled into her music ongoing resentment and rage she suffered over racist practices and prejudices experienced since childhood, poor management received throughout her career, and the popularity of younger white performers who rose like meteors around her and achieved far greater commercial success. Personal, humanizing struggles — alcohol addiction, troubled romantic relationships, and a reputation for being shy to the point of awkwardness onstage but diva-like and difficult offstage — clouded but never eclipsed the talent evident in her voice or her lifelong dedication to enacting political, social, and cultural change.

Late in her career, greater success and recognition emerged — good notices received for her work in films, positive response to the Blues Everywhere I Go album, and in 1999, Odetta received the National Medal of the Arts and Humanities from President Bill Clinton. Now, there is a celebration of Odetta’s life and legacy to be enjoyed, recalled — or discovered — in her 25 albums and this wonderful biography.