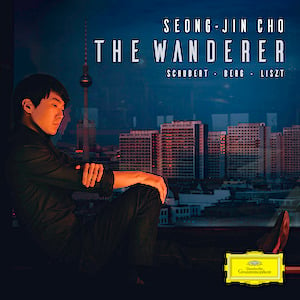

Four entries deep into his Deutsche Grammophon recording pact, 25-year-old South Korean pianist Seong-Jin Cho had been devoting each disc to just one composer. For his fifth CD, titled The Wanderer, he takes on three, shaping the program as if it was a concert recital.

He starts with the Schubert “Wanderer” Fantasy in C Major, leaps ahead in time to Berg’s early, pre-atonal Piano Sonata (insert intermission here), and concludes with a blockbuster, Liszt’s Sonata in B Minor. All three works are single-movement sonatas that develop a handful of ideas throughout their timespans. No encores, though.

In contemplating this program, as heard from a stream, I found myself going back in time to the Ottawa Chamberfest in the summer of 2011 when Marc-André Hamelin opened a recital with the Berg sonata and after cunningly wending his way through Stockhausen’s Klavierstück IX and Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit, wound up with a titanic performance of the Liszt sonata. That recital established Hamelin in my mind as one of the greats of this era. Cho’s program aims toward the same swashbuckling Lisztian destination, if by a somewhat more direct route from Berg.

In contemplating this program, as heard from a stream, I found myself going back in time to the Ottawa Chamberfest in the summer of 2011 when Marc-André Hamelin opened a recital with the Berg sonata and after cunningly wending his way through Stockhausen’s Klavierstück IX and Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit, wound up with a titanic performance of the Liszt sonata. That recital established Hamelin in my mind as one of the greats of this era. Cho’s program aims toward the same swashbuckling Lisztian destination, if by a somewhat more direct route from Berg.

“Wanderer” is crisp, solid, with hints of poetry in the slower passages. Cho isn’t as subtle or flexible as some other pianists in this work, but he’s up to the technical demands and can turn on the razzle-dazzle when needed.

The name Berg may have been fearsome at one time, but nowadays, when kids as young as 9 (Tsotne Zedginidze) can play this Piano Sonata from memory on YouTube, it is long past time to fear anything — especially in this Op. 1. Cho seems more at home in the milieu of this score than in Schubert, feeling the pull of the music’s early Schoenberg hyper-Romanticism.

There is a lot of competition in the Liszt — most keyboard virtuosos get to it sooner or later — and Cho’s is a worthy entry. In the beginning, we don’t quite sense the thunder of Vladimir Horowitz or Jenő Jandó, yet Cho avoids anticlimax in this way, doling out his fireworks carefully. He continues on with astonishing clarity, an attractively crystalline touch, astutely curled rubatos in the lyrical sections, and effortlessly grand conclusions. Cho shares Yuja Wang’s affinity for sharp accents, and he is more involving than Maurizio Pollini. But the rampaging Horowitz characterizes each note more fully, jaw-dropping clams aside. It’s as if Horowitz is teetering on the high wire while Cho makes it all sound easy.