Ernie Andrews, the suave jazz crooner and blues-powered big band belter, was a full generation older than Barbara Morrison, a vocalist equally comfortable interpreting American Songbook standards and 1950s R&B anthems. The fact that they both departed the scene earlier this year less than a month apart linked them in death much as they were in life, as artists who embodied Los Angeles jazz at its best.

Andrews (Dec. 25, 1927 – Feb. 21, 2022) was one of the last direct links to the glory days of the 1940s Central Avenue scene, where he first gained attention as a tall and lanky teenager with a fine-grained, ballad-ready baritone. Born in Philadelphia, he’d spent several formative years in New Orleans as a young teen. Still a student at Jefferson High in South L.A. when he recorded the minor but enduring 1945 hit “Soothe Me,” Andrews got an early start and spent most of his career undervalued and overlooked by everyone but his fellow musicians.

His approach to ballads was clearly inspired by Billy Eckstine’s unabashed romanticism, and he also expanded the Kansas City blues lexicon created by Jimmy Rushing, developing a wide-ranging repertoire that included epically reimagined pop tunes, like James Taylor’s “Fire and Rain.” Part of what made Andrews a quintessential L.A. jazz artist was that despite ranking among the very best in the profession for so long — he was a commanding performer well into his 80s — he always seemed on the brink of breaking through to a wider audience. Instead, record labels overlooked and neglected him, and the music industry in general seemed flummoxed by how best to present Andrews, who infused even the most upbeat arrangements with a streak of melancholy.

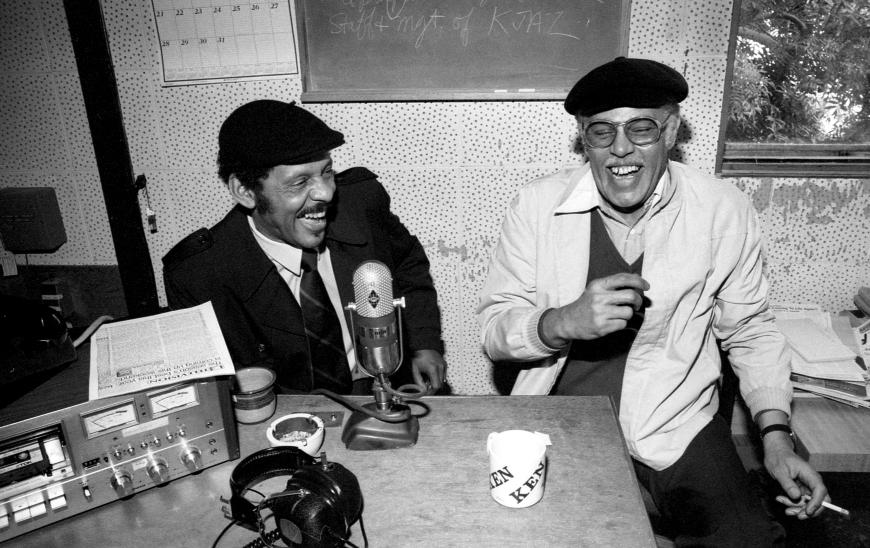

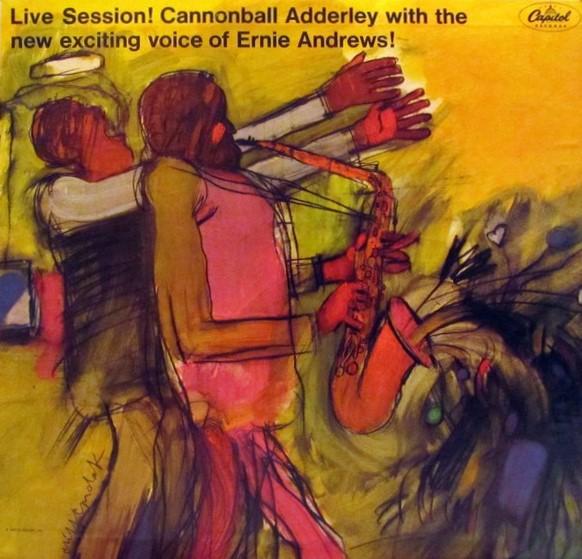

He could have gone the route of Joe Williams, who was already a veteran performer when he parlayed his 1954–1959 stint with Count Basie into enduring fame. Andrews toured and recorded with the orchestra of swing-era trumpet star Harry James, which was dedicated to hits of the past rather than new music, which meant that during his prime years in the late 1950s and early ’60s, Andrews wasn’t establishing himself as a solo act when jazz’s access to the nation’s cultural conversation was fading (a door that largely slammed shut with the advent of the Beatles in 1964). That was the year that alto sax star Cannonball Adderley turned his attention to Andrews, the first of many attempts by his colleagues to showcase the inimitable vocalist.

Cannonball had played an essential role in launching Nancy Wilson’s career in the early 1960s, and he tried the same tactic with Andrews, giving the singer cover billing on the album Live Session! Conveniently ignoring Andrews’s status as a well-traveled veteran, the cover described him as “the exciting new voice.” It’s a stellar album that captures Andrews’s swaggering charisma, particularly on the debut performance of “I’m Always Drunk in San Francisco,” a song that could have done for Andrews what “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” did for Tony Bennett. Instead, the album went out of print, and “I’m Always Drunk” came into Carmen McRae’s eminently capable hands.

After settling in L.A., guitar great Kenny Burrell got to know Andrews and featured him on his high-profile Ellington Is Forever projects in the mid-1970s, which put another high-watt spotlight on the singer. Strangely, no record labels seemed interested in Andrews, not even Concord Jazz, which revived the career of the similarly versatile Ernestine Anderson. Andrews did record some for Concord, but it was as the vocalist for the Capp-Pierce Juggernaut rather than under his own name. Lois Shelton’s 1986 documentary Ernie Andrews: Blues for Central Avenue introduced a whole new generation to the vocalist, while lamenting the decline of a verdant, integrated scene that many feel was targeted by L.A. police and politicians opposed to social equality.

Andrews finally started recording regularly in the mid-1990s, launching a 12-year run that produced half a dozen excellent albums for Muse and HighNote, including my favorites, 2001’s Girl Talk and 2003’s Jump for Joy (which were both produced by tenor saxophonist Houston Person). It seems more than fitting that Andrews’s final recording was on another project designed to thrust him back into the limelight, when he still sounded magnificent at 86. The Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra’s 2014 album The L.A. Treasures Project: Live at Alvas Showroom also featured Barbara Morrison, a singer whose bright optimism paired effectively with Andrews’s dignified reticence.

Morrison (Sept. 10, 1949 – March 16, 2022) was far better documented during her career than Andrews, recording some two dozen albums of her own while appearing as a guest artist on projects with everyone from Johnny Otis and Jimmy Smith to Doc Severinsen and Kenny Burrell. A jazz-informed blues singer who could swing with authority, she thrived in the expansive Venn diagram terrain where jazz and blues overlap. An L.A. institution for five decades, she was dedicated to building the Southland scene, creating the Barbara Morrison Performing Arts Center in Leimert Park as a crucible for nurturing rising talent and the neighboring California Jazz & Blues Museum.

On paper Morrison seemed destined for a life in music. Piano legend Erroll Garner was related to her mother, and the brilliant tenor and soprano saxophonist Lucky Thompson was also a relative. But she never met Garner, who passed away in 1977, or the reclusive Thompson, who had been off the scene for years when he died in 2005. She credited her father, a fine pianist and doo-wop singer, with encouraging her to become a professional vocalist.

Born in Ypsilanti, Mich., Morrison got her first break in the early 1970s when she and a friend happened into a small L.A. dive where alto saxophonist and vocalist Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson was holding forth. She wasn’t familiar with the trailblazing Texas entertainer, whose music encompassed jump blues, R&B, and bebop, but when her friend informed him that Morrison was an aspiring singer, he invited her to sit in. He ended up hiring her on the spot and became an invaluable mentor.

“He taught me everything I know,” Morrison told me in a 1994 interview for The San Diego Union-Tribune. “I used to call him ‘Dad’ and ask him, ‘Dad, when am I going to get my own style?’ He said, ‘You just hang in there and quit listening to all those singers. You ain’t Gladys Knight. You ain’t Aretha Franklin. Get you some horn players, get you some Coleman Hawkins and some Sonny Stitt, and listen to those standards.’”

Following his advice, she avoided the influence of the popular female singers of the time and grew into a versatile performer with a sound steeped in the blues and informed by jazz and gospel phrasing. “I think the biggest influence on me was Johnnie Taylor,” Morrison said. “He’s one of the most wonderful blues and R&B singers in the world.”

She never signed with a major label, but Morrison recorded prolifically and performed widely with many of jazz’s most celebrated artists, including Jon Faddis, James Moody, Jimmy Heath, Gene Harris, Cedar Walton, Terence Blanchard, Ron Carter, and Houston Person, who produced several of her best late-career albums for Savant, including the ballad-centric A Sunday Kind of Love (2013) and I Wanna Be Loved (2017). She remained active after losing a leg to diabetes, a setback that led the L.A. scene to rally to her aid with a marathon fundraising concert in 2011 at the Local 47 Musicians Union. Like Andrews, Morrison kept L.A. connected to its most potent musical roots, and their passing leaves a void that seems more difficult than ever to bridge.