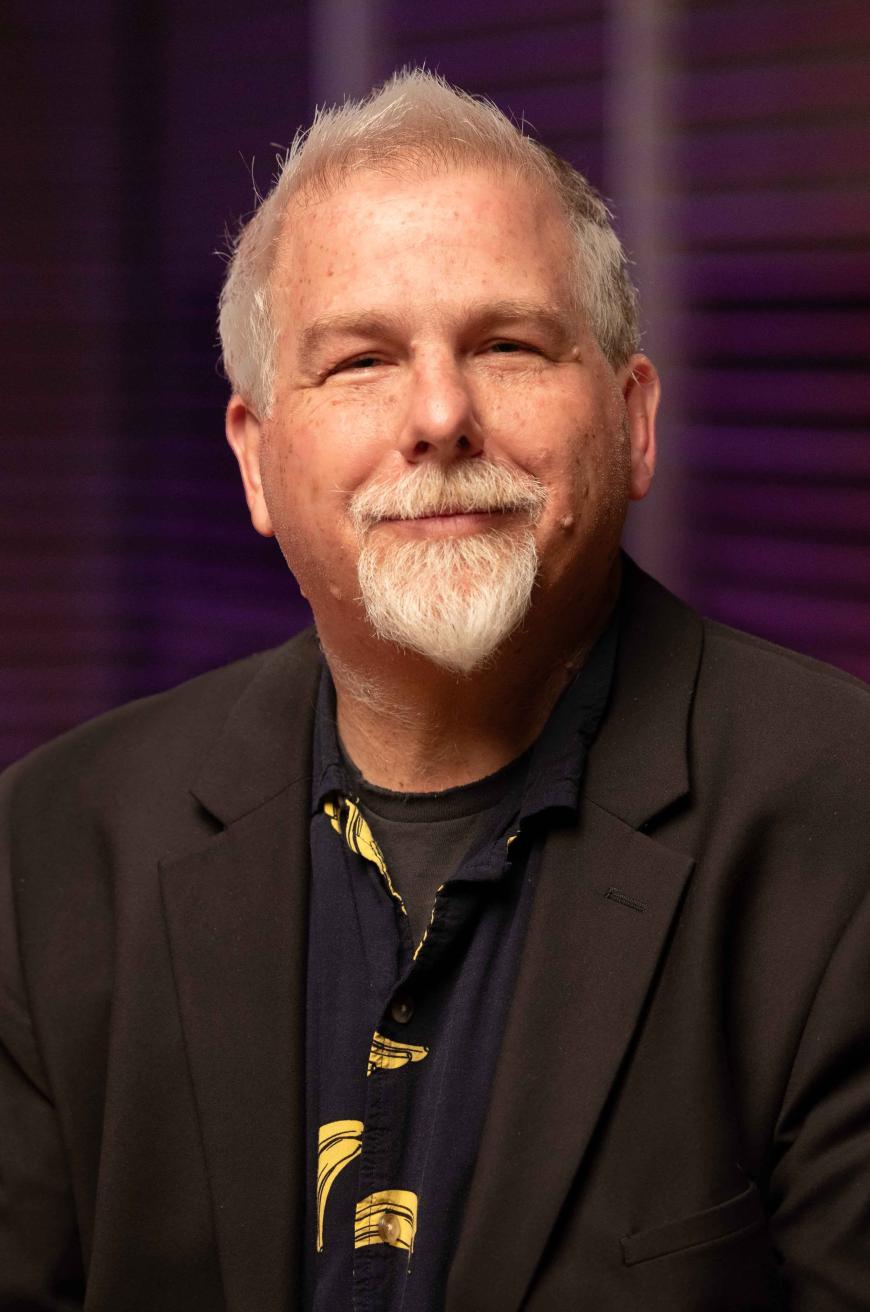

At first blush, the suggestion seems outlandish, almost blasphemous, but Steve Horowitz’s grin is more Cheshire Cat than Mad Hatter. He repeats the assertion as his co-author and musical comrade Scott Looney nods in assent. “Game music is the new American Songbook,” Horowitz says.

If your idea of gaming is pulling out the old backgammon set or settling in for a night of Monopoly, prepare for a plunge down the rabbit hole. Horowitz and Looney want to tell you about the vast game frontiers attracting a disparate array of composers, from aspiring students looking to break into the industry to established artists versed in jazz, contemporary classical music, songcraft, and electronica. It’s a dominion where composition intersects with cutting-edge technology powered by an economy that dwarfs Hollywood.

The music created to accompany and enhance the quests, missions, adventures, and world-building that unfolds in games doesn’t stay in the digital realm. “It’s weird to say, but the new American Songbook that kids want to play comes from this game music,” Horowitz says, noting that there are bands and jam sessions devoted to game music, as well as websites with lead sheets for this music.

Vocalist, pianist, and radio host Jennifer Miller Hammel has built up a following for her streaming channel for Classical California, Arcade, which plays “hours and hours of today’s and yesterday’s music for interactive media, plus classical pieces used in games or that inspired today’s composers.”

The point was made vividly last month at a San Francisco Conservatory of Music (SFCM) reception for Horowitz and Looney’s groundbreaking new textbook, The Theory and Practice of Writing Music for Games, which draws from their hands-on experience as game composers and Horowitz’s popular course on composing for games at San Francisco State.

In February, SFCM announced Horowitz’s appointment as executive director of its Technology and Applied Composition (TAC) program, which is why SFCM junior Cullen Luper was playing a solo piano medley of the impressionistic Prologue from the game Celeste, by Lena Raine, and the moody “Drifter” from Counter-Strike, by Mark Levine — two of the half-dozen composers on hand (or video link) in Cha Chi Ming Recital Hall answering nitty-gritty questions from students. Some of the composers were in town for the five-day Game Developers Conference that took over the Moscone Center March 18–22.

It’s a fascinating moment in the video game industry, which has been hit by a round of layoffs after a massive wave of growth during the pandemic, when the demand for digital entertainment seemed bottomless. Still, according to industry reports, total U.S. consumer spending on video game content amounted to $57.2 billion in 2023, a 1-percent increase from the year before (the global game economy is more than three times larger). SFCM’s decade-old TAC program has been at the vanguard, and in the way Horowitz and Looney’s textbook is the first of its kind, many other music schools are just now starting to think about incorporating this vast world into their curriculums.

“Where we’re at, in terms of game music education, is where jazz education was in the 1960s,” Horowitz says. “It was a huge thing to add a jazz class at SF State in 1968. Now every single school has a jazz program. There was a time when conservatories looked at film scoring like, ‘Oh my god, you’re polluting the water.’ We were very early to this. We’re on the cusp, but I expect that to start changing rapidly.”

In the process of rethinking and redesigning TAC, Horowitz seems to have landed at the ideal place. SF State’s limited access to expensive new technologies and aversion to partnering with private companies “meant we couldn’t work with Dolby and put their logo on a project,” Horowitz says. SFCM President David Stull, who made a point of dropping by the book-release party to introduce the new executive director, “is a genius at these public-private partnerships,” Horowitz says. “These facilities are off the charts. There’s no other program like this in the world.”

There are far too many angles to game music to cover in one article or book, but one takeaway from the textbook, which features a series of case studies focusing on various composers, is that many musicians in the industry intersect with the worlds of jazz and contemporary classical. “I can’t tell you how many of my CalArts and Mills friends are working in the game industry,” says Looney, an experimental-minded pianist and composer who studied with Morton Subotnick, David Rosenboom, Frederic Rzewski, Roscoe Mitchell, and Wadada Leo Smith. “It’s a valid art form. There’s a trio of musicians playing Nintendo songs at Grace Cathedral tomorrow night.”

Looney and Horowitz, a bassist who studied composition at CalArts with Subotnick and Mel Powell, have made their own contribution to the budding scene with Fantasy Kingdom, an antic album of experimental remixes of Japanese video game music, featuring saxophonist Dan Plonsey and drummer Jim Bove. Most of the themes are drawn from widely popular games like Street Fighter II, Final Fantasy III & IV, and the namesake Kingdom Hearts. But Looney emphasizes that “there are a million different kinds of games and approaches.”

One of the composers at the book-release event, Rich Vreeland, created the score for Mini Metro, a game that lets users create their own transit systems. “Every single element makes one tone, and you can build up the composition by building up the transit system,” Looney says. “It’s serial music, applying what [Olivier] Messiaen and [Arnold] Schoenberg did.”

The confluence of high modernism and video games might seem jarring, but film composers long ago adopted these concepts and techniques for another art form that was also once dismissed as beneath the notice of “serious” critics. The students Horowitz teaches today are largely unburdened by time-worn hierarchies. He recently finished going through around 100 student auditions for SFCM, “coming in from incredibly diverse backgrounds,” he says.

“Some are trained concert pianists who want to use technology to help enhance their composing. Some are singer-songwriters. Others are interested in writing for film or games. They don’t have that uptown-downtown thing. They want to write a string quartet and for games and for movies. There are no boundaries.”