As a music lover born on this day forever marked by Kristallnacht and having lived with its genocidal consequences, I am grateful for James Conlon’s Recovered Voices project — as well as for memories of concerts and operas he has led, but that’s another story.

The subject here is the current state of Conlon’s decades-old efforts, now housed within the framework of Colburn School’s Ziering-Conlon Initiative for Recovered Voices, and the background of the Initiative’s statement of purpose, “Undoing injustice, when and where one can, is a moral mandate for all citizens of a civilized world.”

Conlon, 71, is artistic director of the Initiative as well as music director of the Los Angeles Opera where he originally initiated a major part of Recovered Voices. Supported by Los Angeles philanthropist Marilyn Ziering, the Initiative’s purpose is to preserve and present works of composers who perished in the Holocaust or whose music was suppressed by the Nazis.

The history is delineated by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum:

Music has been essential to German culture and national identity for centuries. For the Nazis, music was seen not only as a source of national pride but also a tool that could be used to reshape German society to reflect the racial and cultural ideology of the Third Reich.

Shortly after taking power in 1933, Nazi officials sought to “coordinate” German music by establishing the Reich Chamber of Music to supervise all musical activities in Germany and encourage music that upheld “Aryan” values. Orchestras and conservatories were nationalized and subsidized by the state, while popular performers were recruited to serve as propaganda outlets for the Reich.

Jewish musicians were stripped of their positions, and those who chose or were forced to remain in Germany formed the Jewish Culture Association (“Jüdischer Kulturbund”) to operate an orchestra, theater, and opera company composed of Jewish performers.

The Nazis also ascribed a racial element to music, denouncing popular music like jazz as well as modern, avant-garde orchestral compositions as corrupting influences on traditional German values. A 1938 exhibition in Düsseldorf entitled “Entartete Musik” condemned this so-called “degenerate” music and the artists who performed it.

How did Conlon’s involvement begin? Pretty much as many music lovers discover music new to them: on the car radio (or whatever the contemporary equivalent may be).

Some 30 years ago, in Cologne (where he was leading both the Gürzenich Orchestra and the Cologne Opera), he was driving home after a concert when unfamiliar, “fantastic” music on the radio caught his attention, and — as often has happened to many of us before being plugged in permanently — sat in the car long after arriving home to hear it all.

It was Conlon’s first experience of Alexander von Zemlinsky’s music, a body of works he has since helped to bring into the mainstream, with memorable performances around the world, including in San Francisco. “I knew the name, but wasn’t familiar with his music,” Conlon told SF Classical Voice, “I explored his works and started conducting them, and when EMI offered to select programs for recording, performances spread through both live concerts and CDs.”

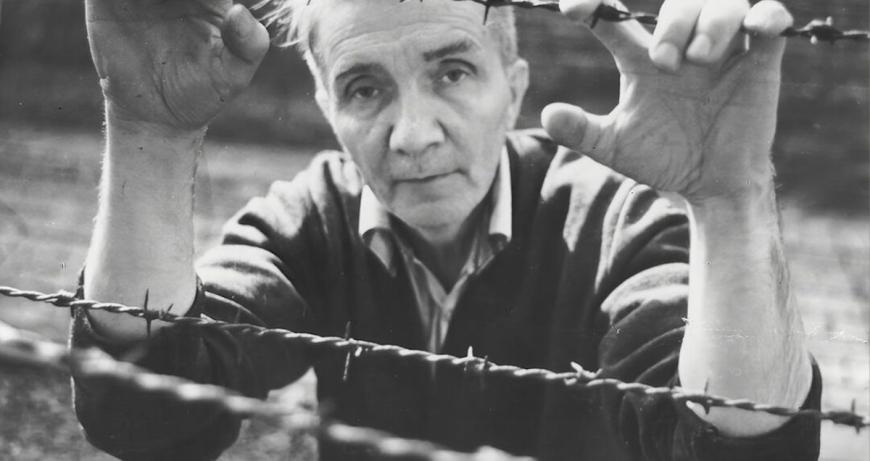

Zemlinsky, born in Vienna into a Hungarian-Slovak-Bosnian family, was raised in the Sephardic Jewish faith of his mother but converted to Protestantism in 1899. He became the friend and collaborator of Arnold Schoenberg in Vienna and occupied important positions there. With the rise of the Third Reich, when hundreds of Jewish artists escaped to the U.S., Los Angeles became a musical center for many German, Austrian, and East European composers and musicians, including Schoenberg, but Zemlinsky ended up in New York, unknown and unwell. He died in 1942 in Larchmont, New York, at age 70.

Refugees like Zemlinsky, as well as enslaved and murdered musicians in concentration camps and elsewhere in the 1930s and ’40s form the core of the composers and performers whose voices were stilled until long after the end of World War II, and whose work started to be recovered only in past 30–40 years.

Those who were murdered in concentration camps are not the only musicians whose voices are being recovered. “The concern is also about those banned, silenced, and disappeared by Nazi suppression,” Conlon emphasizes.

“As soon as I began to discover the traces of Zemlinsky,” Conlon says, “additional names appeared: [Franz] Schreker, and the composers who wrote music in the Theresienstadt ghetto, and I asked myself what was happening to me, and the feeling was of a revelation that was coming back to me.”

In response, he (and a growing number of organizations in recent years) have found, studied, performed — “recovered” — previously unknown works by Jewish, Roma, and gay musicians, or those who were otherwise deemed political opponents of the Reich.

And that’s how today we hear, often for the first time, music by Pál Hermann, Erwin Schulhoff, Walter Kaufmann, Viktor Ullmann, Dick Kattenburg, Mieczyslaw Weinberg, Gideon Klein, Paul Ben-Haim, Szymon Laks, Renzo Massarani, Walter Arlen, Berthold Goldschmidt, Ilse Weber; and see Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Hanns Eisler, Franz Schreker, Ernst Krenek, and many others experience new popularity.

Conlon’s involvement is independent of religious affiliation or, he says, “tokenism.” Not comparing himself to Righteous Gentiles, who saved lives during the Holocaust, Conlon tells about his background: “I was born and raised in New York from a Catholic family with Irish, German, and Italian roots. I was the fourth of five children, from a home with little money. My great-grandfather, Giuseppe di Grazia, was a musician like me and came from Calvello, a small town in Basilicata.”

Even so, he had much to catch up with: “Once in a restaurant I did not know how to say knife and I asked for a dagger, thinking of Rigoletto — in the libretto, he has a dagger. They all laughed. I realized it was time to study Italian.”

The reason for his passion for the music and the people he is espousing, what he calls his “mission,” Conlon says, is well represented in his essay for the Orel Foundation:

I believe that the spirit of this “lost generation” now needs to be heard. The creativity of the first half of the 20th century is far richer and varied than we commonly assume. Alongside Stravinsky, Strauss, and other major and more fortunate figures, the varied voices of composers from Berlin, Vienna, Prague, and Budapest, whether Jewish, dissident or immigrant, reveal much about the musical ferment of their time.

Their music, I believe, is accessible and relevant. Further, American musical culture owes an enormous debt to those who emigrated to Hollywood and Broadway, bringing their distinctive personalities with them, creating a style that has since evolved into a characteristic American one.

The cliché “there are no lost masterpieces” reveals our own ignorance. Entire civilizations, along with their masterpieces, have been destroyed by war since the beginning of human history. Various forms of censorship have repeatedly affected artists and works, and continue to do so.

There are three fundamental aspects to be taken into consideration when approaching the revival of this music: moral, historical, and artistic.

Undoing injustice, when and where one can, is a moral mandate for all citizens of a civilized world. We cannot restore to these composers their lost lives. We can, however, return the gift that would mean more to them than any other — that of performing their music.

The Initiative currently offers a series a freely streamed programs, beginning with video presentations about Erwin Schulhoff (1894–1942), “a fascinating, prolific, and multifaceted composer who embraced a full panoply of styles and influences from his era.”

The first episode was released last week; “Tradition Meets Dada” will be available on Nov. 16; “Erwin Schulhoff: A Classical Music Jazz Prophet” on Nov. 30; “The Twenties and a Turn Toward Socialist Realism” on Dec. 14.

The Recovered Voices online series will continue with episodes featuring Robert Elias (“What and Why ‘Degenerate’ Music”) and Dr. Lily E. Hirsch (“Jewish Women Composers During the Nazi Regime: Twice Censored”) to be released later this season.

Among many efforts to find, perform, honor, and recover the voices and works of Holocaust victims are:

-

Daniel Hope’s “Forbidden Music” concerts and recordings, some focusing on Terezin, a concentration camp near Prague, used as a Nazi showcase, and holding area for some 150,000 Jews, including thousands of children, eventually sent to their deaths at the Treblinka and Auschwitz extermination camps in Poland.

-

The Music of Remembrance program, with a strong representation in San Francisco. The program’s broad scope includes the persecution of Roma musicians.

-

ORT World’s Holocaust Music program has scores of articles about “Music from the Camps,” “Ghetto Music,” and “Music After the Holocaust.”

-

Shoah program by the Chamber Music Society of the United Nations Staff Recreation Council.

-

NPR programs about Holocaust music.

-

The Bailey School of Music, in collaboration with the KSU Museum of History and Holocaust Education, presents music and commentary to commemorate Kristallnacht on Nov. 9 at 7:30 p.m. CST.