For almost a century, the Bay Area has been without an excellent, medium-size hall for classical music. There are some exciting small-to-medium-sized venues around — Burlingame’s Kohl Mansion comes to mind for its vibrant immediacy and directness; UC Berkeley’s Hertz Hall for its relative intimacy and, in certain sections, its warmth, beauty, and natural reverberation; the 333-seat Florence Gould Theatre in the Palace of the Legion of Honor for its jewel-box intimacy and lovely acoustic; and, perhaps the best of the lot, the rarely available Stent Family Hall at the Menlo School (used by Music at Menlo).

Yet none of these halls, even Hertz, is consistently available for use by the extended Bay Area’s major performing arts presenters: San Francisco Performances, Cal Performances, and Stanford Live.

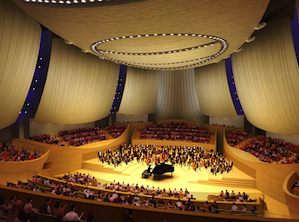

Enter, in the span of just a few months, three new venues designed with acoustics in mind. The first to open, 1,400-seat Weill Hall in the Green Music Center at Sonoma State University, has also ushered in a major new performing arts series whose offerings include the San Francisco Symphony, Santa Rosa Symphony, and world-class soloists and ensembles.

Among Weill Hall’s many offerings, the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Vocal Recital series is a gift from heaven — this season, it underwrites recitals by Joyce DiDonato, Karina Gauvin, Barbara Cook, Elina Garanca, Tara Erraught, Stephanie Blythe, the Tallis Scholars, and more. Add in Tanglewood-like indoor/outdoor concerts in multiple genres that can accommodate up to 5,100 spectators, and you have a major addition to the “extended” Bay Area music scene.

Stanford University’s 842-seat Bing Concert Hall in Palo Alto, with its “vineyard” seating that rings the stage, has become the new home of Stanford Live. If Weill has the San Francisco and Santa Rosa Symphony Orchestras, Bing has the Philharmonia Baroque and Stanford Symphony Orchestras. Rich in both classical and jazz offerings, Bing is a major venue.

Finally, there is the new SFJAZZ Center Miner Auditorium, whose flexible seating is adjustable to accommodate 350–700 music lovers. It may have been designed with jazz in mind, but it will most certainly host concerts sponsored by San Francisco Performances and other organizations during the retrofit and renovation of Herbst Theatre and the Green Room, taking place from May 1 this year to August 31, 2015. (Not all performances can be moved to the San Francisco Conservatory of Music’s extremely live concert hall, which has its share of acoustic problems.)

As someone who divides his time between writing about and reviewing both classical music and high-end audio, I’ve learned that no matter what acousticians or promoters say, or how well designs read on paper or appear to the eye, the ear tells the final tale. Hence, to evaluate the acoustics of our new halls, I attended multiple performances in all three venues, attempting to sit in a different area of the hall each time. That wasn’t always possible, especially in the case of sold-out Bing Hall, though I tried.

At Weill, I attended three “formal” concerts plus the preopening public tuning. In Bing, I attended four concerts, each very different in character. And while my initial visit to SFJAZZ’s Miner Hall for a supposedly unamplified concert failed to fulfill expectations when bassist Dave Holland’s road crew insisted on providing amplification for his gig with pianist Kenny Barron, I was able to augment feedback from an acoustical evaluation session attended by representatives of local arts organizations with a rare opportunity to spend a half hour wandering around the hall while the wonderful pianist David Udolf played everything from Debussy to swing on SFJAZZ’s new, hand-picked American Steinway.

The Jewel: Weill Hall

When Sanford I. Weill, chairman of the board of Carnegie Hall and former CEO of Citigroup, Travelers, and Fireman’s Fund, was first asked to contribute funds for the completion of the Green Music Center, the recent transplant to Sonoma County called on some of his friends to help him evaluate its potential as a world-class music venue. First Lang Lang, and then Yo-Yo Ma, visited the hall, played their hearts out, and, from the vantage point of the stage, praised the hall’s acoustics. Given their endorsements, Sandy Weill not only plopped down $12 million, but also helped mastermind a wonderful, El Sistema–like outreach program, which is destined to transform the cultural life of Sonoma County, as well as the music education of all students in the area, ages 5 and up.

My first visit to Weill took place months before the official opening, when acoustician Larry Kierkegaard arrived to “tune” the hall. To hear what music sounded like when the hall was filled to capacity, he attended the first open rehearsal of the Santa Rosa Symphony in its new home.

Even before a host of problems had been addressed, the hall’s superiority with higher-pitched instruments was evident, both from one of the parterre boxes on the ground floor and then from three different seats in the front and middle orchestra. Unlike San Francisco’s Herbst Theatre, where a flute’s singing tone is submerged beneath audible puffs of the flautist’s breath, here the flute sang free. Whether in a solo cadenza or with full orchestra, its tone floated gratifyingly throughout the hall.

Returning for mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato’s glorious recital with Il Complesso Barocco, and seated on the aisle at the back of the first orchestra section, I marveled at the freedom and beauty with which her voice projected from the stage, and how wonderfully it was complemented by the hall’s resonant glow. Not since I attended Frederica von Stade’s farewell recital in Carnegie Hall had I encountered a voice surrounded by so much natural “air” and resonance. My only concern was with the Baroque ensemble’s lower-pitched instruments, which sounded submerged beneath an overall treble fabric.

I marveled at the freedom and beauty with which her voice projected from the stage, and how wonderfully it was complemented by the hall’s resonant glow. – On Weill Hall

For the San Francisco Symphony’s first concert in Weill, I arrived accompanied by Grammy Award–winning recording engineer Keith O. Johnson of Reference Recordings. Johnson’s 100-plus recordings for the label have garnered three Grammy awards and eight additional Grammy nominations. Among audiophiles, Johnson is a living legend.

Seated on the aisle, toward the rear of front orchestra, Johnson and I were equally impressed with the hall’s acoustics. His only complaint concerned a smudging of woodwind focus, which he felt could be easily ameliorated by placing instruments such as flute, bassoon, and clarinet farther from the stage’s rear wall. My only concern was that timpani and basses lacked the bloom and impact heard in similar prime orchestra seats in the S.F. Symphony’s Davies Symphony Hall.

When I returned to hear the S.F. Symphony, conducted by Charles Dutoit, I sat in seat P1, a few rows back in the middle orchestra section and on the side. There, the orchestra sounded surprisingly clattery. After intermission, I switched to the rear row of the first orchestra section, which not only smoothed out the highs, but also delivered much of the midrange warmth and bass foundation that I had hoped for. My hunch is that, with further adjustment of draperies and other acoustic accouterments, this “sweet spot” can be enlarged.

No Minor Achievement

Ah, the miracles of Facebook. Through the postings of “Friends” I discovered that on Jan. 29, recording engineer David Bowles had evaluated the acoustics of SFJAZZ’s Miner Auditorium. Bowles, who has served on the national board of governors of the Audio Engineering Society, and whose Swineshead Productions records both Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra and New Century Chamber Orchestra, was part of a party of six — three representatives from Philharmonia Baroque and three from S.F. Performances — who enlisted the Alexander String Quartet to play Britten, Mozart, and Haydn in the mostly empty hall in order to determine if it could serve as a suitable replacement for Herbst during the latter’s closure. Bowles, who formerly played in Philharmonia Baroque and is the partner of its music director, Nicholas McGegan, was asked to give his impressions of the hall’s acoustic from an audio engineering perspective.

“Though the acoustic is dry,” he shared by phone, “I am impressed by the relative evenness of sound throughout the venue. The air-handling system is also very quiet — much better than the noisy, inefficient fans in Herbst and the War Memorial Opera House. And despite the dryness, the sightlines are wonderful, and it has a new and trendy look.”

Bowles had multiple opportunities to move around the hall as the ASQ played for a half hour. The quartet, in turn, experimented with the best place to perform onstage. Together with their audience of six, they discovered that while they sounded far more present to the audience when they moved forward, toward the edge of the proscenium, they couldn’t hear themselves as well as when seated farther back.

“Though the acoustic is dry,” he shared by phone, “I am impressed by the relative evenness of sound throughout the venue.” – Recording engineer David Bowles, on Miner Auditorium

Although Miner Auditorium cannot accommodate as large an audience as Herbst, Bowles opined that it would work fine for PBO during the renovation. He was far less enthusiastic about the acoustics of the 1,800-seat Beaux Arts Nourse Auditorium at Hayes and Franklin Streets, adjacent to Davies Symphony Hall, which City Arts & Lectures is renovating. Unless that organization can do something about the hall’s “diffused and unfocused” sound, Bowles doesn’t find it suitable for music presentations.

Modest Suggestions

After my first attempt to evaluate Miner Auditorium was handicapped by amplification, the folks at SFJAZZ made it possible for me to evaluate the hall’s acoustics while David Udoff luxuriated on the organization’s Steinway. While I can confirm that the hall’s acoustics are dry rather than wet — the gratifying liquidity of sound you can hear in more-reverberant acoustics isn’t present amid Miner’s industrial-strength decor — it doesn’t suck up sound, as Herbst is notoriously wont to do. I can also confirm that while there is a natural decline in the vibrancy of higher-pitched tones as distance from the stage increases, the distribution of sound is remarkably even throughout the hall.

I believe that with two changes, the hall would work much better for nonamplified music. The first would be to transform the ceiling-high white backdrop behind the stage into a tunable, acoustically reflective surface that would help project sound into the space. I’m not suggesting a generic acoustic shell, as is currently in use in Herbst, but rather a tunable backdrop tailored specifically to the acoustic of Miner.

The second would be to light that backdrop with gelled spots to bring some life into the otherwise drab, über-techno interior. (I’m not suggesting that colors change throughout the performance to reflect transformations in emotion and mood.) I don’t know if Miner’s predominantly gray interior was intended to give the hall a modern, “cool” look, but I really thought the celebration of the industrial revolution was well behind us.

Big Bing Problems

Keith Johnson wasn’t happy. At the talk that preceded the Stanford Symphony Orchestra’s performance of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and Fifth Piano Concerto (with Jon Nakamatsu), he had walked around Bing Hall, and discovered that the speaker’s voice sounded exactly the same no matter where he sat or stood.

“Everything you hear is first reflections,” he opined. “There are no reflections off the ceiling, which sustain the sound and give you the sense of dimensionality you get in a traditional shoebox design. This is the problem with acoustician Yasu Toyota’s designs”

Johnson knows of what he speaks. His Reference Recordings is beginning to record the Kansas City Symphony in the 1,600-seat Helzberg Hall, for whose acoustics Toyota is also responsible. Note that Johnson received a Grammy for his work on the high-resolution SACD surround sound mix of his previous project with the KCSO, Britten’s Orchestra, which was recorded in Community of Christ Auditorium.

“Some of Toyota’s spaces fail to communicate dimensionality,” Johnson continued. “You can’t tell where instruments are placed.” Indeed, when I closed my eyes during the second half of the concert while seated on the aisle in H128, which you’d think would be a great seat, I could have sworn that the basses behind Nakamatsu’s piano were stage right, when in fact they were stage left.

But that was only a small part of the problem. The orchestra’s highs were certainly acceptable — the violins sounded lovely — but lower-pitched instruments seemed overly resonant and muddled, and the lowest notes were a disorganized mess. I could see the timpanist banging away, but, for the life of me, I could hardly hear his instruments over the din. Not even the trumpets, which count on rear reflections for their characteristic timbre, sounded right. Equally dismaying, there was so much resonance that, had I never opened my eyes, I might have thought that two Mahler-sized orchestras were blasting away in an acoustic that could not possibly do them justice.

“Some of Toyota’s spaces fail to communicate dimensionality. You can’t tell where instruments are placed.” – Recording engineer Keith O. Johnson, on Bing Hall

During intermission, the most telling comment I heard was in the men’s room. “That sure is one helluva resonant hall,” one patron said. Everyone else remained silent, perhaps because they were stupefied by what they had heard.

In Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto, which requires a sparser orchestral sound, the piano’s midrange and lows were again muddy, and the timpani unfocused. Rather than floating over the orchestra in the sublime middle movement, the piano waddled through. None of the crystalline clarity and focus that this music demands was present. Not even the brief passage where the timpani played solo beneath the piano was clear.

I returned for three more concerts. SFCV’s Anatole Leikin, visiting the hall for the first time, ascribed the “unfocused sound” the professor heard at Emanuel Ax’s solo recital to his lidless piano. Having already experienced Bing’s acoustical problems, I thought Ax’s playing sounded less muddy than Nakamatsu’s. Perhaps removing the piano’s lid actually helped clarify the sound, by eliminating its amplifying effect.

I had thought that the directional amplification in use during percussionist Glenn Kotche’s concert would help focus his sound, but it didn’t. Instead, much of his pounding sounded muddy, especially when he let loose at high speed. Even more surprising was the unamplified portion of vocal chamber ensemble Cappella Romana’s concert, where its baker’s dozen singers sounded “curiously removed from their natural element, somewhat dry, and lacking in impact,” to quote from my own review. I can only conjecture that it takes a certain level of volume to excite resonances in the hall. But once they’re excited, watch out!

While Weill Hall’s shoebox acoustic was designed to allow for fine-tuning, I’m not sure how much tuning is possible in Bing, where the vineyard arrangement central to its design appears to be at the (ahem) root of the problem. Given that computer genius Jonathan Abel and the team at CCRMA (Stanford’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics) could electronically re-create the long-tail reverberation of Istanbul’s Hagia Sofia in Bing, perhaps they can use computer-guided electronic reinforcement to create a healthy acoustic amid the confusion. But what will that do to the promise of unamplified bliss that is the hall’s raison d’être?

Only time will tell. Meanwhile, for as many music lovers who leave Weill Hall marveling at the golden glow of its sound, there are others who depart Bing Hall shaking their heads.