"We often think of the scheduled broadcasting of news, information and entertainment as having begun in the 1920s. But we're wrong," says last week's BBC program on the subject. (The program itself is available at this address for a couple of more days.)

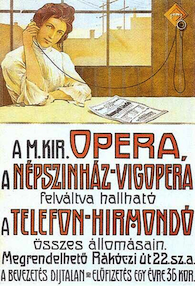

It was in 1893 in Budapest that Theodore Puskás opened his telefonhírmondó or "Telephone Newspaper." Subscribers to this telephone service could enjoy a daily timetable of foreign, national and local news, sport, weather, fashion, stock market reports, language lessons, music, theatre and much more.It was delivered by a team of journalists, copy-writers, editors, announcers, and engineers which would be familiar to any radio station today. To our ears, Telefon Hirmondo would have sounded uncannily modern. For example, there would be live relays of church services, theatre productions, concerts, and opera performances and reports direct from parliament and sports events.

Laurie Taylor travels to Budapest to uncover this extraordinary story of "radio before radio." He visits a special exhibition at the city's postal museum and takes a look inside Hungarian State Opera, whose performances were broadcast live via Telefon Hirmondo from the 1890s.

Not so fast, says Mark Schubin, who has been giving us the fascinating history of the surprisingly ancient roots of today's HD opera telecasts:

While BBC gave full credit to Puskás for the Paris demo, it was actually devised by Clement Ader. The first commercial opera-delivery service was in Dundee, Scotland in 1882; the first involving payment to the opera company was in Lisbon in 1884 — both long before the Budapest service.Puskás deserves big credit for two things: the first newscast (and the journalistic infrastructure to support it) and the most effective distribution system (which, unfortunately, he never fully described).

Schubin's full treatment of the subject can be found at his website on "Media Technology and Opera History."

Puskás (1844-1893) had a fascinating, relatively brief life, criss-crossing the world and associating with some of technology's giants. Of Transylvanian ancestry, at a young age he became engineer for an English railroad company, then lived in Vienna, moved to Colorado at a late phase of the Gold Rush (not having much luck), moving on to London and Brussels, later joining Thomas Alva Edison in Menlo Park, helping to develop telephone exchanges.

Called by some the father of the internet's forerunner, Puskás opened the first Hungarian telephone center in 1881, with 25 subscribers. An unsubstantiated story says Edison visited Puskás in 1911, and credited him with the invention of telephone centers. The established pioneer was French engineer F. M. A. Dumont, whose British patent for telephone exchange is dated 1851, long before both Edison and Puskás.