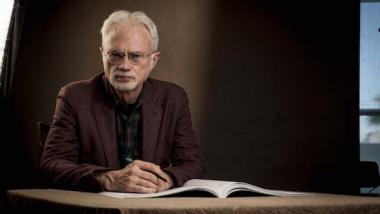

In what sometimes seems like the Dark Ages, it’s all the more vital to recognize a Renaissance man. It’s no stretch to apply that term to Berkeley-based composer John Adams, whose 70th birthday, on February 15, will be celebrated with musical performances all month and all year, here and across the globe.

As the creator of some of the most frequently performed contemporary operas and long-form orchestral works, Adams has ever been an innovator, as well as a musical spokesperson for progressive insight and activism, including feminism, and for cross-cultural expression. His three-decade-long relationship with the San Francisco Symphony has contributed some 30 works to the orchestra’s repertoire. Adams and his wife, landscape photographer Deborah O’Grady, support Berkeley’s Crowden School (which entwines academics and chamber music) and encourage the education and career development of young composers. The Los Angeles Philharmonic and Berlin Philharmonic have engaged Adams as creative chair and composer-in-residence, respectively, and he conducts regularly, across the U.S. and Europe.

After the Cal Performances and San Francisco Symphony events this month, recognition of Adams will extend throughout 2017 to the San Francisco Opera’s world premiere, in November, of Girls of the Golden West, the latest in his three-decade-long collaboration with director and librettist Peter Sellars.

Adams is also an informed contributor of reviews and commentary to major publications, and the author of an autobiography, Hallelujah Junction, which critic Mark Swed called, " intelligent, reasoned and caring." The same may be said about this recent phone chat with Adams, from his Berkeley homestead.

How did the Symphony decide what to do with your birthday?

I was asked by Brent [Assink, SFS executive director] what I’d like to do, and rather than doing something 20 or 30 years old, I wanted to bring two of my larger, newer pieces [to Davies Hall, on Feb. 16–18 and Feb. 22–25]. One is The Gospel According to the Other Mary. I just returned last night from Berlin, from hearing Simon Rattle do an unbelievable performance of it. And there’s Scheherazade.2, which has been done quite a bit in the last two years, but not in San Francisco.

For you, how does your newer differ from your older work?

The music I wrote in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s had a more identifiable relationship with Minimalism, and tended to be a little simpler. It’s like certain painters who were influenced by Cubism, then [later] realized its limitations and wanted to take it to a more complex and universally expressive language. I think Other Mary is probably the most wide-ranging use of all my musical language and technique.

What’s the text [compiled by Peter Sellars]?

It’s a really remarkable mixure of Biblical sources — John, Matthew, Luke, even Isaiah — and writing from our own time, much of it by women. The texts by Catholic social activist Dorothy Day are probably the most important, because they emphasize the fact that Jesus’s entire adult life was at the service of homeless people, the kind you see outside the [San Francisco] Civic Center, really desperate and miserable. And there’s a segment of Day’s working with Cesar Chavez. It’s the only sacred oratorio in which the word “Teamsters” is mentioned. [Laughs]

And how does Mary Magdalene herself figure in?

There was a period when people, particularly male biblical scholars, decided that she was a reformed prostitute, which I think was very demeaning, and there’s no proof of that at all. I think of her as probably someone who may have been sexually abused as a child, who felt this enormous magnetic attraction to Jesus, which, in my interpretation, was both physical and deeply spiritual.

Looking ahead to Girls of the Golden West, about which you and Peter spoke at the Opera’s season announcement, is there a feminist theme to your work, which Scheherazade.2 also fits with?

I guess so. Certainly we saw, in Hillary Clinton’s campaign, that this is one of the critical themes in our society right now, whether it’s young women on campuses trying to protect themselves from violation, women fighting for control over their own bodies, or the larger event of women trying to free themselves from traditional roles and be empowered. This theme stimulates me, on an expressive, artistic level.

Peter and you had more to say about how your opera will connect our current political drama, including “fake news,” with the circumstances of the Gold Rush in the mid-19th century.

All over the East Coast and the world, they were reading articles about how they’d be able to bend over and pick up a nugget of gold and become instant millionaires, and when they got here to California and it didn’t turn out that way, it turned into the typical kind of racial accusations we’re hearing right now. That ended up, 20 or 30 years later, with the Chinese Exclusion Act. So last night, when I’d just gotten back from Berlin and came in through the San Francisco Airport and found this huge crowd of people [protesting the Muslim travel ban], it was actually thrilling and at the same time disturbing.

I was there, with my wife.

Wonderful.

Has the landscape of the California Gold Country influenced your writing for the opera?

Not so much in the opera, but in certain orchestral works. It would be corny to say I “painted” the Sierras. Remember that famous story of when Bruno Walter went to visit Mahler, and Walter looked up at the Alps. And Mahler said, “Oh, don’t even look at them, I’ve already composed them.” I don’t try to do that sort of thing.

I’d assume your relocating to the West Coast eventually prompted you to use Spanish.

That came about because of the piece El Niño. I wanted to write an oratorio and I asked Peter to help assemble a libretto. So he gave me poems, with English translation, and I said, it’s really time for me to learn Spanish. This was about 2000. So I got a tutor and learned, over a four-year period. Then I went to Venezuela and did rehearsals, in Spanish, and I’ve also used Spanish in The Flowering Tree, The Other Mary, and now the new opera. Spanish is just more full of vowels, more singable, like Italian.

Tell us a bit about your curating SoundBox, the first of this month’s Symphony birthday events [on February 10–11]?

Even before that, on Feb. 3–4, there’s a Cal Performances event, Available Light, with [choreographer] Lucinda Childs [and architect Frank O.Gehry, performed at and streamed to Facebook from Zellerbach Hall]. And I have to say, parenthetically, that I really adore [executive and artistic director] Matias Tarnopolsky, who’s done so much at Cal Performances.

SoundBox wanted some of my music, but I wanted also to introduce some young composers I feel are very strong and pointing towards the future of American music. I’d already done the world premiere of Andrew Norman’s Try, with the L.A. Phil, about four years ago, and I did it just last week in Berlin. Then there’s a work my wife and I commissioned by Jacob Cooper, who’s also an extremely talented video artist. I think it’s called Ripple in the Sky; it’s an imagined dreamscape, for string octet and a singer and video, of Schumann’s last. incoherent thoughts of Clara as a young woman. And last but not least, there’s a performance piece for two woman singers and a small ensemble, by a young woman who I think is on the verge of a major career, Ashley Fure. It’s almost impossible to describe, performed in almost complete darkness, with huge subwoofer spearkers that will make the building vibrate, almost like an earthquake.

I spend a great deal of my time with young composers now; we have a program — I’m embarrassed to say it’s called the John Adams Young Composers Program — that’s been going on for about 10 years at the Crowden School. I also do a lot of new work with the L.A. Phil, [in] what’s called the Green Umbella series, and my wife and I have the Pacific Harmony Foundation, which commissions works from young composers for the Cabrillo Festival.

I've always admired your continuing interest in Crowden, which both of your kids attended.

Our daughter Emil, would have been a much more active violinist, but she broke the same arm three times when she was about 15. Typical teenager. She had to largely give up the violin, but she became a painter, and she’s having enormous success now. And our son, Sam, is now composer-in-residence with the Chicago Symphony; Riccardo Muti is going to premiere a piece of his. And I also have to say, I’m bursting with pride about Crowden, because just last week, when Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic did The Other Mary, the concertmaster was none other than Noah Bendix-Balgley, who went to Crowden in the same class with Emily.

I was also glad for your inaugurating the Symphony’s New and Unusual Music Series, in 1980. What’s new and unusual these days?

I’ll say two things. First, this is a much better time to be a young composer; there is a lot more interest in and support for new music. Of course, what young composers are writing now is more interesting, and not quite as grimly confrontational and theoretical. On the downside, I’m disturbed at the timidity and risk-averse attitudes of the major institutions. It’s wonderful that SoundBox has been a success, but I’m alarmed how little new music there is on the subscription programs. And that’s going on all over the country. After Alan [Gilbert] leaves the New York Philharmonic, I’m concerned about the same thing happening there and elsewhere.

Is that primarily economics, John?

Well, yeah. I recently had an exchange with a person on a search committee for new administrators, and the issue was, do we need somebody who understands classical music. The explanation was, orchestras are such economic burdens, we have to rely on marketing and spreadsheets and the bottom line of ticket sales and attracting funders.

Do you think it’s okay for art to lose money?

That’s kind of a negative spin, but if you look at Beethoven, all those great works that now we can’t get enough of were supported by wealthy people. You could say, yeah, Prince Lichnowsky lost money and didn’t get anything in return, except the satisfaction of having supported the work. My point simply is, in the world of art, you have to be willing to take risks, and I see that less and less in the large orchestras and opera companies in this country. Art does lose money, but it’s an essential part of our human existence, it expresses the highest and most noble aspirations of human beings. And it shouldn’t be treated as commerce.

I’m with you, John, and I hope fulfilling risks will be taken in a lot of areas of our lives. Happy birthday, and thanks for being a beacon.

Thank you! I don’t always feel like that when I get up in the morning, but it’s kind of you to say.