During a total eclipse, light is obscured, time suspended, animation stilled, power subsumed. There is wholeness and nothingness — and within that spherical zero, there is everything around which life revolves.

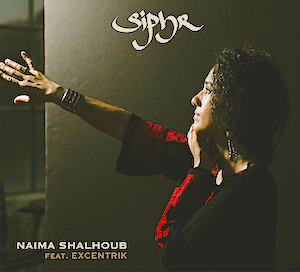

Oakland-based Lebanese-American vocalist, composer, and educator Naima Shalhoub translates zero-sum everything into Arabic to become Siphr, the title of her debut studio album. Nine tracks fuse American blues, jazz, and hip-hop with classical and contemporary Arabic music to form an unbreakable chain linking freedom, captivity, joy, sorrow, pain, separation, identity, political protest, and spiritual power.

The album is a collaboration between Shalhoub and Excentrik (Palestinian-American musician Tarik Kazaleh) and includes cellist Ed Baskerville, and bassist Marcus Shelby. Recorded at Women’s Audio Mission in San Francisco, the compositions are titled numerically, with subtitles indicating the significance Shalhoub draws from each number.

The album is a collaboration between Shalhoub and Excentrik (Palestinian-American musician Tarik Kazaleh) and includes cellist Ed Baskerville, and bassist Marcus Shelby. Recorded at Women’s Audio Mission in San Francisco, the compositions are titled numerically, with subtitles indicating the significance Shalhoub draws from each number.

Although Siphr took three years to complete and originated in 2018 in Beirut, during time Shalhoub spent visiting family and traveling in Lebanon, the music seems anchored in relevancy for today’s audiences. Like her first album, Live in San Francisco County Jail, recorded with incarcerated women she led in weekly social justice circles, there is in the music commitment to artistic excellence and to a greater goal: radical restoration and healing.

In a conversation ranging from details of specific tracks to the art of listening, Shalhoub speaks candidly about composing, expanding the definition of classical music, and the beauty of silence and remembrance.

Track four with Marcus Shelby you say channels the blues and presents singing as resiliency in both American jazz forms and Arabic music. What does “singing as resiliency” mean?

What I mean by that is the way that in all indigenous traditions, music is not a commodified tool. It’s not something abstracted, it’s a part of everyday life. That includes the power of improvisational music, channeling communities and creating in the moment. Whether that’s through war, land occupation, or celebration. In Arabic culture — and I’ll be specific to my family being from Lebanon — music is a part of the culture so ingrained.

Regarding resiliency, what I mean is through war, while being refugees and during displacement, music and poetry continue to be created. It’s a different history than the context of where the blues emerges from: Black American history and creativity is born from a different struggle. But the power in both [musical responses] means survival. Survival could mean without art and without music, but music and poetry are key in remembrance. Arabic art is tied to remembrance and remembrance is tied to liberation. When we stop creating, that is a concern. Audre Lorde has said poetry is not a luxury. That especially applies with Arabic culture.

The lyrics on this same track are drawn from words spoken by Arabic prisoners you met in the Roumieh Prison in Lebanon. Was nuance lost in translating from Arabic to English?

There is so much nuance lost. It was hard to translate. It’s easier to come close in conversation, versus writing it down. The part that was most difficult, Door oh door/In Roumieh it’s hard, is (an example). Door can mean gate, but also, the opening of the prison. The Arabic word for hard is used in so many contexts. So without knowing the (poetic) language, trying to translate it, it loses some of it. The last line of that verse where it says, my soul itself will leave, but here I’ll still be without an open door, it’s meant to be poetic; not quite a metaphor, but it’s dramatic language. It’s like, although my soul, a part of me, might leave the prison, my body is still here — just open the door, will you? It’s like an exclamation. I had a hard time understanding that at first. On the flip side, Arabic lends itself to the blues. That felt natural.

Did you add your words to theirs?

I didn’t write any of the words or eliminate or add words because the incarcerated men wrote them. I used all of their words and we put it into melody during that session.

What can you tell me about setting the groove for the song?

It was a collaboration between me and Excentrik, my co-collaborator through the whole album. I wanted it to be a medium-tempo blues. I wanted the rhythm to contain the tension, to have that expression. I had played the song live: solo, in a duo, with a band, experimenting in iterations. I settled on a tempo that felt really good for the lyrics, for the cadence of call and response between vocal and guitar.

Tanik really added to the feeling, almost a Mississippi Delta vibe. He added slide guitar, and then we found “mystery percussion.” In the studio, he took off his shoe and that’s part of the percussion. He was on the ground, tapping his shoe on the floor of the recording studio, with the mic right there. And he found a Velcro, nerf-like ball and scraped it across his hand. You’ll hear that in the recording. We called all of that “ball-and-shoe percussion.” You construct and build and create the sound you want to go for. That worked with elements of the blues and Arabic elements within the lyrics and the way I’m singing them.

You say these nine songs are meant to be listened to in order, uninterrupted. Did the final order require a lot of juggling or did it come out organically?

That’s a great question. If you see the image on the back of the liner notes: a full eclipse with nine (partial eclipses) around it. If you imagine it as a sketch with one circle in the middle and nine circles around it; I used that as my geometric map through the whole album. I would take notes, because I needed the order to be even more intentional. I needed the connections, one through nine. Bringing Tanik in, we mapped out the songs so we didn’t have to do juggling at the end. One of the things was that [track] nine would end where [track] one began: with the same rhythm. We were plotting it like a sonic map, as well as a thematic map. Eight was the last one completed. It was the biggest headache. We had nothing, then in a couple days we just did it. That was the most unique one.

Do you have a particular method for songwriting?

For this album, I had a theme around the composing and the songwriting. My spirit had a story, something it wanted to say. I didn’t know yet what that was, in my mind, but I started to steward it for each song. There was an energy and spirit [behind] matching the number and the theme. Before I started vocalizing, I spent most of the time in meditation.

When I sat down at the piano and played with percussion, melodies would come. For number five, I had nothing arranged ahead of time. I sat down at the piano and both the lyrics and the progression came. Three, I had that chorus written three years prior, but no verses. I had the hook, and that felt right to my spirit, but I had no idea. It was pulling teeth to write verses to match something to what the chorus was trying to say. I didn’t want it to be clichéd or too cheesy, like forcing it. Finally, in the third iteration, the lyrics came. Then I went to the studio and recorded that final version.

You make a comment in an interview I watched that “Black-culture music” — soul and blues — is America’s classical music. What did you mean by that statement?

I could call it indigenous, too. I like to choose classical so we’re not just thinking about European music as classical. All traditions have classical music. What is classical music? That’s the next question.

There’s a certain classical period in history and other parts of the music world use the term classical as origin music. Growing up in public schools and learning what classical music is, what was taught is that this is origin music that can contextualize music today. So we have symphonies, and we’re learning from Beethoven and Mozart and using music theory.

Marcus Shelby and I talked about referencing the blues, which African-American music references, as classical. It’s about a power choice and the ways we’re taught history, the ways we’re taught about things that are “classics.” Classic literature was Emily Dickinson, Whitman ... and it’s like, what about the other writers? Why aren’t they classics? Why aren’t we looking at other places in the world? Why is it always Europe?

Are there songwriters you look to for inspiration?

Depending on the melody and on certain singers that I vibe with in their timbre, I go to people like Billie Holiday and Nina Simone. They have two very different timbres, but there’s something in their voices that I learned from. Holiday has this way; she sings in her nasal passage in a way that’s so expressive. When I say nasal, some people think it’s a negative thing. But it’s her command of a range of expression, it’s like she’s singing with the technical (aspects) matching her emotions. It’s a higher range than Nina Simone and for me, higher than I would be comfortable in. There’s more upper cavity part of Holliday’s voice and with Nina, I hear more of the deeper timbre, the chest voice.

Are there songs written by other musicians that you feel meant to sing?

Billie Holiday didn’t write all of her music, but there’s one piece she wrote, You Better Go Now. It’s a less-known piece: I just want to live in that song and sing it over and over. To jump decades, there’s Mercedes Sosa, an Argentinian singer. She was known as the voice of the nueva canción movement, when the music was speaking about freedom and uniting South America. I used to sing her songs all the time. They’re timeless. If she sang them in concert, the entire audience would sing along. It’s communal music, the melody easy to remember, easy to sing with other people in a circle.

Also there’s neo-soul singers like Erykah Badu. I love her music, how it’s so rhythmic. She’s singing poetry she wrote, but it’s so catchy, memorable and soulful. It’s present with the times, with clever lyrics.

To the Arabic side, [Lebanese composer] Wadih El Safi. There’s an Arabic term, mawwāl, when you’re basically singing poetry. The music doesn’t stop, but everything pauses and there’s a drone. It might be the trill of the oud [Arabic lute], and the singer goes off on runs and sings the poetry.

Do you believe the voice is more expressive of emotion and speaks in this way with greater authenticity to human ears than instruments might?

I don’t know about more than, but the voice inside the human is going to resonate differently than an instrument that is outside of oneself. The honesty in the voice, for example, there’s a difference in mimicking. Even the exact timbre and expression, if one isn’t honest, isn’t putting themselves into a song and feeling it, people can tell. Soul knowns soul, spirit knows spirit. I say that because I was before Covid, for about a year and a half, I was doing weekly circles with girls in Alameda county. I brought in one of my Arabic songs in the tarab tradition. Tarab is soulful, deeply emotive music. You can’t fake it. You have to get in there. What is different in the voice is the honesty in the expression in performance and being able to tell if someone is present. You need technique and the discipline to learn it. When [emotion and technique] come together, there’s nothing like the human voice.

Are separation or feelings of otherness an immigrant or refuge might experience amplified by something other than lyrics?

Trying to compose in a way that has that tension, I don’t think there’s just one way to do it. Rhythm is one way, and having tension between different sections of the song can speak to that separation experience without having the lyrics do that. Marcel Khalife, a composer, oud player, and vocalist, takes Palestinian poems that are all about the homeland and the wrongs done and being separated. He composes music that’s just brilliant. Some of the compositions are very simple, from songs written to be sung a capella or all the way to [music for] an entire orchestra. In the melodies there is so much tension, longing, love, separation. There’s extending a phrase and turning it into vocal runs as the strings are underneath it. The voice becomes almost like a string instrument that sounds just like a violin. It creates a tension with the instruments and it creates the beauty and longing.

You also write and sing about positive themes: surviving, coping, finding balance, joy, and healing through community. Is this less natural? Do you have to remind yourself to be hopeful?

It’s very natural. Especially on this album, like number two, it is a prayer and I couldn’t wait to write that one. I was excited to have a prayer of affirmation. When it’s coming from a place of truth, it feels good. I wanted on this album to trace the difficulties and complexities of life, but also the triumphs, joy, divinity, and prayer.

What have you been listening to recently?

I’m not listening to a lot of music right now. Sometimes I need a lot of silence. I just don’t want to hear music. I want to listen to nature, what’s in the room. I like quiet. Music I do listen to, it’s usually the kind that speaks to my spirit. Old school gospel music, I love. At the beginning of shelter-in-place, I was listening to Gnawa music from people of North Africa. They have this instrument called a gimbri [a three-stringed rectangular lute-like instrument] that is hypnotizing. Their singing is unbelievable. It puts me in a trance.

What do people not listen to often enough?

Live music. It’s getting less and less. Someone would argue and say, no way, all I love to do is listen to swing, blues, jazz that’s all live. But I’m thinking larger populations and of what I see on social media, I fear live music and live instruments will become obsolete in a hundred years. With less and less young people having opportunity to learn live instruments and with my work with young people, my perspective is coming from that. I love playing with sounds in my recording studio, but I ask them, do you guys even know what just live tracks sound like? My album, it sounds folky compared to what they’re listening to.