When Robert Garland stepped into his new role as artistic director of Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH), it was just the next inevitable step in his long association with the company. The 55-year-old dance troupe will be performing April 20–21 at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek, the company’s third annual appearance at the venue since 2022. It’s one of two California stops for DTH this week, with the company also performing at UC Davis’s Mondavi Center on April 17.

Garland is eager to continue showing DTH’s stylistic breadth through the choreographers in its repertoire — from the epitome of classicism, Marius Petipa, to neoclassical modernist George Balanchine to current dance makers such as Christopher Wheeldon, Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, Stanton Welch, William Forsythe, and Nacho Duato. None of these choreographers are strangers to the Bay Area dance audience.

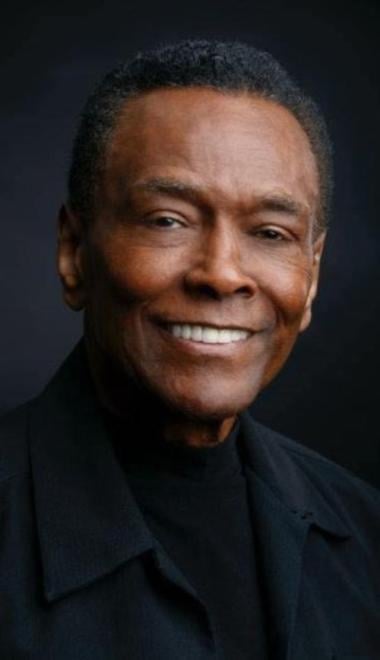

In a phone interview, Garland shared the details of his path to becoming the head of DTH, where he has spent much of his career as a dancer, teacher, and choreographer. Growing up in Philadelphia, his first influences were his parents. “My mother played the piano; she was self-taught and was a musician in church. And my father was a big sports guy, so we always were doing very physical things. I think I joined the physicality and the music together, so it was perfectly logical that I would end up picking dance as the thing that I was most interested in.

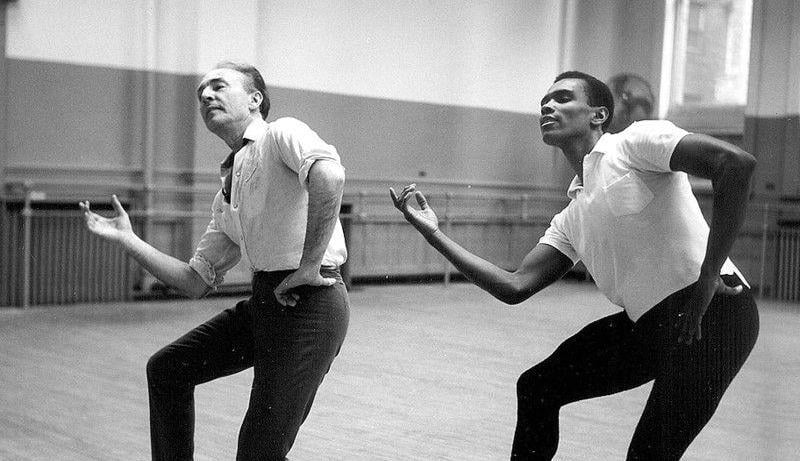

“I started rather late, as boys tend to do. But boy’s jobs were also plentiful in dance, [as were] scholarships, as I learned really quickly. By the time I was a teenager, I was dancing with the Philadelphia Dance Company, founded by Joan Myers Brown. She always hired New York artists to come and teach. A lot of DTH dancers in the mid- to late-1970s would all come and teach ballet class. One was Karel Shook, who was a co-founder of DTH with Arthur Mitchell.”

After graduating from high school, Garland headed to New York, where he studied dance at The Juilliard School. He mentioned, “I had teachers, Alfredo Corvino and Hector Zaraspe, who were wonderful and pushed me with their belief that they thought I could do it. And I thought, ‘All right, why not?’”

Once Garland earned his degree, Mitchell hired him as an apprentice. “But he knew I had an interest in the library. So during my times when we were off, I worked as an assistant librarian and eventually became the official librarian archivist for Dance Theatre of Harlem. I loved history, and it was the easiest way to see all the videos and read all the books and everything else. After a year, I became a member of the company and then moved up through the ranks. But I always maintained a connection to the library and archives.”

Garland danced with DTH for 15 years and then told Mitchell he wanted to focus on choreography. Mitchell responded that he had been thinking about appointing a resident choreographer. He knew from his own experience with Balanchine at New York City Ballet (NYCB) that, as Garland explained, “it just always made for an easy relationship to develop repertory with people that you knew. And so he said I could be the resident choreographer. He said, however, ‘I would like for you to be director of the school as well.’”

Garland continued, “And that was what taught me everything I needed to know about how to run a dance business. How to look at a balance sheet, how to be responsible to students, how to be responsible to the parents of the students, and all those things that can come up when running a school.

“When I came on in the school, Arthur Mitchell, brash as he was, decided to hire five full-time teachers. They had been part-time up until that point. So we had a Russian teacher; a woman that knew the Royal Academy of Dance, or The Royal Ballet, method; a teacher that was more or less American-trained; and then there was another man who had trained in the Dutch syllabus. Also, we had an Asian woman who had studied in China. It was a wonderful opportunity to learn from these people.

“Again, Mitchell had the vision and foresight to do that. I really loved him. Even when I was moving into a professional space as an apprentice, I was still very much a student. He taught me so much about responsibility, about showing up, about caring for your neighbor or your colleagues. He was really good at teaching you how to be not only a great dancer but a great human being.”

Another source of inspiration for Garland is Balanchine. “He was the blueprint for the American ballet aesthetic. Even to this day, when I rehearse my dancers, I say to myself, and to the dancers, ‘He’s really the genius here. Look at what he’s done.’ And they respond to how phenomenal he is.” And Mitchell, who was the first Black principal dancer with NYCB, is again the connecting thread here. “I did a panel discussion at New York City Center [recently] with Wendy Whelan, from NYCB, about Arthur Mitchell. We got to talking about just everything that he gave to us and gave to the art; I mean, literally, he gave his body to the art of dance and particularly ballet, which was amazing for a Black man in 1955.”

Garland admits that, like Balanchine, “I love Suzanne Farrell [a former principal dancer at NYCB]. In 2004, during a residency program at The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., Mitchell put me in charge, so I was working the program. He would come down and coach the kids while I was choreographing. One day, he was teaching in the studio, and I was on the floor counting some music out. And I see these feet go by me, doing pas de bourrées to the beat of the music. I look up, and it’s Suzanne Farrell. She had [her own ballet] company at The Kennedy Center. I almost started crying and said, ‘Ms. Farrell, Mr. Mitchell is in the studio.’ She said, ‘Arthur, he’s in there?’ We went into the studio, and all her dancers sat down, and Arthur Mitchell and Suzanne Farrell talked to them for the rest of the day and took all of their questions.”

Another inspirational dancer for Garland is Kyra Nichols. The former NYCB principal dancer recently set Balanchine’s Pas de Dix on DTH. Garland said he admires her because “she embodies the best parts of Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. I would say she’s amazing in that sense.”

Every director has his or her own vision for shaping a company and moving into the future. That vision can be based on what’s come before, but growth and maturity also are important factors. Garland offered, “It definitely is based for me on what’s coming forward — because the question of representation in ballet still unfortunately exists. My repertory will be built both on contemporary works and works from the African American diaspora but also expand the Balanchine side of our repertory. I’m really, really interested in continuing the work of having the cultural diaspora reflected in the works I choose. … I would love to have Ronald K. Brown. He’s authentically devoted to the African diasporic moving body.”

Garland feels strongly that “people need so deeply and desperately the historical context of organizations.” Last year, he was commissioned to create a ballet for San Francisco Ballet’s “next@90” festival, a celebration of the company’s 90th anniversary. “When I worked at San Francisco Ballet, my first day of rehearsal in the large studio, they had pictures of the founders around the room. For about two hours, I went to each picture, told them [the dancers] who they were, why they were important, the ideas behind their work, and their efforts in terms of creating a foundational dance institution. By the time it was over, the dancers understood they’re in the middle of a legacy. And I said, ‘Yes, you are a huge legacy.’ That part for me is really crucial because at that point the dancers can begin to take ownership once they have the history. That’s why I’m myself stepping into this role here.

“At some point in time, clearly it was reckoned that they could do without knowing the history, that all you needed to know was how to do a plié and a tendu. But that will only get you so far. For me, coming from the African American culture, we’re very big on our history because we feel our young people cannot move forward without it.”