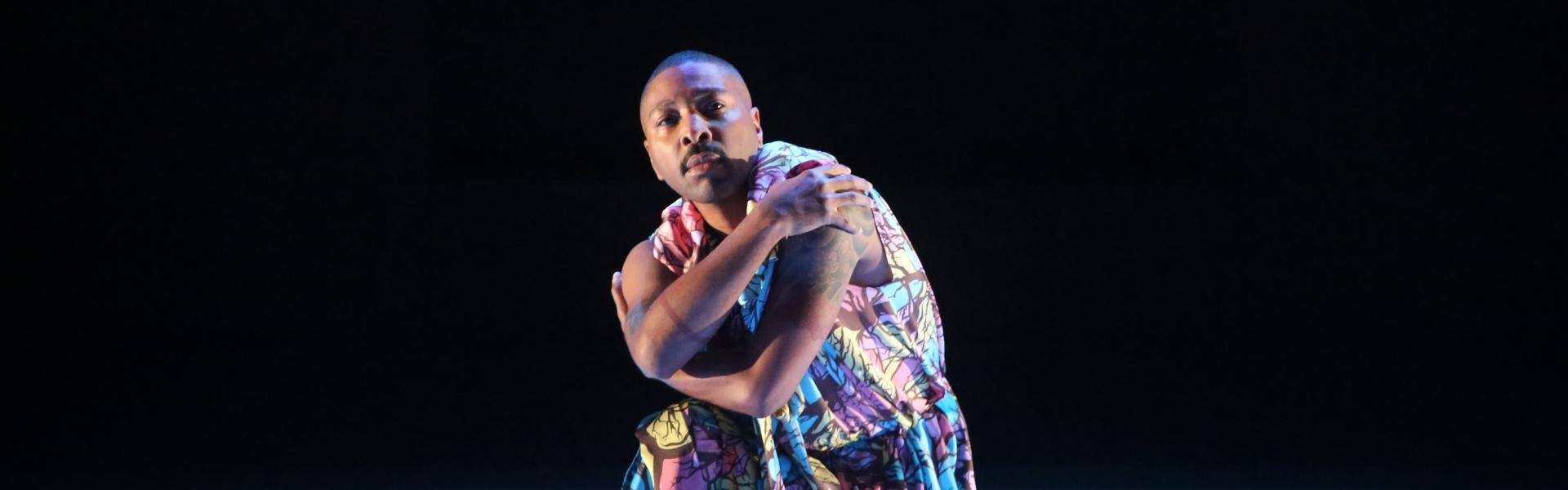

With his inimitable vocabulary of postmodern abstract moves — or, as he calls it, “gumbo style,” which blends Black dance with classical ballet techniques — Kyle Abraham, 45, has been making evocative works for decades. Since founding his New York-based troupe, A.I.M by Kyle Abraham, in 2006, he’s also racked up some of the arts’ most prestigious honors, including a 2012 Bessie Award and a 2013 MacArthur “genius” grant.

And now, Southern Californians have three chances to see Abraham’s 10-member troupe. Beginning Feb. 15, the company is at USC’s Bovard Auditorium (Abraham is currently on the faculty of the USC Glorya Kaufman School of Dance) with its evening-length work An Untitled Love (2021). Requiem: Fire in the Air of the Earth (2022), Abraham’s take on Mozart’s famous work, with music by pioneering producer, composer, and EDM artist Jlin, lands at The Soraya in Northridge on Feb. 18. And winding up its mini SoCal tour, A.I.M presents a mixed repertory bill at San Diego’s Balboa Theatre Feb. 22.

And Bay Area audiences can catch Abraham and company earlier in the month, Feb. 11 and 12 at the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco.

The Pittsburgh-born Abraham, who was also a Princess Grace Statue Award recipient in 2018 and last year was honored with a Dance Magazine Award, began his dance training at the Civic Light Opera Academy and the Creative and Performing Arts high school in his hometown. Continuing his studies in New York, Abraham received a B.F.A. from SUNY Purchase, an M.F.A. from the NYU Tisch School of the Arts, and an honorary doctorate from Washington & Jefferson College.

In addition to performing and developing new works for A.I.M (short for Abraham.In.Motion), which The New York Times deemed “one of the most consistently excellent troupes working today,” the bicoastal artist has made commissions for a variety of dance companies, including New York City Ballet, The Royal Ballet, and Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

And if there’s anything Abraham can’t do, well, nobody’s mentioned it to the multi-hyphenate yet. Indeed, he was tapped to serve as a choreographic contributor for Beyoncé’s British Vogue magazine cover shoot in 2013, and A.I.M’s dance film “If We Were a Love Song,” a series of poetic vignettes set to the music of Nina Simone, received a New York Emmy nomination in 2022.

SF Classical Voice recently chatted with Abraham by phone, covering topics from audience expectations to his SoCal gigs and his choreographic process.

When did you first realize that you wanted to be a choreographer?

It’s tricky to say because I feel like the second I was introduced to dance, I was choreographing. I was choreographing at church camp to songs I shouldn’t have been — the “Poison” song from Bell Biv DeVoe, which is not a church camp kind of song — from when I was in elementary or middle school. I remember making dances to show my parents my interest in studying dance at an early age before I winded up doing so.

When I was in my senior year in high school, I thought at that point I would be a choreographer because I felt I was too old to be a dancer. It was a thing where I was just seeing these dancers who had all these skills and the knowledge of codified forms that I didn’t have. It wasn’t only because I loved making dances, but it seemed like the practical choice for me at that time.

Your love of making dances is certainly on display in Requiem: Fire in the Air of the Earth, which addresses mythology and Afrofuturism. What was the work’s genesis?

Initially, Jon Nakagawa from the Mostly Mozart Festival [and director of contemporary programming at Lincoln Center] asked me if I would ever consider doing something to Mozart’s music. I was drawn to the Requiem because of my affinity for more depressing subject matter, but early on in the process, I was told by Jon that we wouldn’t have a live ensemble playing the music. And I’m thinking it’s Mostly Mozart at Lincoln Center, so because of that, I started to wrap my head around the idea that here’s a Black choreographer taking on Mozart’s Requiem, and I didn’t want it to seem canned.

[Wondering] how I could respond to that led me to thinking about Jlin as a collaborator. This helped me shift my approach to choreographing this work, and I started thinking about ideas around reincarnation, the afterlife, and the album artwork for [Jlin’s] Black Origami. Ideas around folklore and mythology seemed in tandem with the afterlife and Black futurism as well. I was also thinking about goddesses from different cultures in mythology and that they could have conversations with one another.

Had you worked with Jlin before, and had you been a Mozart aficionado?

I hadn’t worked with Jlin before, but I worked with her music. I made a [2018] solo, Show Pony, that’s now in the A.I.M repertory and is currently in the Hubbard Street [Dance Chicago] repertory a year or two before I started working with [her music] in my company in our Requiem. I was also playing her music from top to bottom in my technique classes.

[As for being] a fan of Mozart, it was great to grow up playing classical music but also [to see it] finding its way into pop culture in my elementary school days, through Amadeus, the film, and loving and learning classical music. It was really from age 8 or 9, when I studied piano for several years but switched to cello. I was playing while studying dance for another year or so and had to draw my focus, which ended up being dance.

While you were in residency at Jacob’s Pillow in October 2020, you said that Requiem, which is a complete revamping of Mozart’s last work and features planetary sets and lighting by longtime collaborator Dan Scully, is driven by intention and direction, not necessarily choreography. Can you please elaborate on that?

It depends how people consider the choreographic process. In the two evening-length works I had been creating over the last two years — Requiem and An Untitled Love — the ways in which I went about those processes were night and day. In Untitled, 90 percent of the material is generated from my body and the text I’m writing. But with Requiem, a lot of what I chose to do [was less make] a handful of phrases or sequences for dancers to learn, but more giving them prompts to generate material and have another dancer make a variation and allow that to mutate in a way that could still be very much A.I.M — but also having my lens on it in my nerdy ways.

So, what is your choreographic process, i.e., which comes first: music, subject matter, steps, collaborating with your dancers?

It’s that thing that isn’t spoken about enough. Even if I generate every single step, it’s still a collaboration. So much trust needs to happen — trust from me to a dancer. The way in which I collaborate or start a work, it’s never really the same. What can fall in line a lot of times is me making a playlist of songs — not creating to them but the way some will, say, create a mood board.

Maybe I’ll read a long list of books or listen to a lot of music that connects with me — and not that I need to go into the studio to generate material. That can switch every time. But with Mozart, I’d studied the music before I made a step. Initially I did make some material to original compositions, and I gave several prompts and task-based exercises. But An Untitled Love was the opposite; I knew what I was doing.

Which brings me to the question of what you look for in a dancer.

It varies. There are some dancers who are great at replicating material or doing it just like me or better than me but with a clear lineage to what my intention is. And some are great at generating material. Ideally, they can do both. That they don’t look like me and I’m drawn to their differences is [like] I’m cooking something. What they bring — does it highlight the dish, or would it upset the balance with their newness? I consider that. I also love it when dancers have a voice when, or if, you ask them their opinion. If they don’t [have one], then nothing about that is inspiring to me.

How do you deal with audience expectations, especially with regard to world premieres?

It’s more that I’m curious about the audience, especially a new audience. Coming to The Soraya for the first time, it will be interesting to see how [Requiem] will be perceived and received, knowing it’s nothing I’ve done before. This show is a lot. I’m curious to see how audiences [relate to] it in its most extreme way. I’ve made a lot of works that are much more subtle, and this is so not that.

I think it’s exciting and interesting to see how an audience can follow you on your journey and stay curious. For me, I try not to repeat myself. Untitled Love is a specific work that’s the week before the repertory program. The repertory can shift and change, and having a rep program is unlike a full-evening work, and that’s exciting for audiences and dancers.

I understand that when An Untitled Love — a celebration of Black love and Black culture — was performed at The Kennedy Center last April, the Obamas were there. What was that like?

It was really exciting meeting the Obamas. We went to a special room in The Kennedy Center and met them and some of their friends that were there. It was beautiful and special for me, of course, but the thing I had a lot of pride in was the dancers. Since my parents are deceased — my father passed in 2011 and my mother in 2016 — it was the idea that the dancers could say to their parents that they met the Obamas. It was such a beautiful thing to take in.

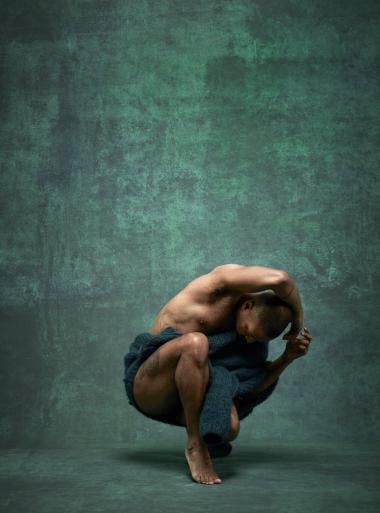

In 2013, the year before Wendy Whelan retired from New York City Ballet, you made a duet, “The Serpent and the Smoke,” for her Restless Creature project. And you danced with her as well. Are you still performing?

I have performed since then. I did a big solo in 2018, Indy, and I toured that. The tricky thing with me is I don’t want to take opportunities away from dancers performing. Sometimes the story of me performing may take over other works on the program, and I don’t want to do that. I would love to find opportunities for me to dance, but they may have to be separate from A.I.M so that they don’t interfere with my company shining.

Your schedule is, to say the least, hectic. How do you relax?

By reading and sometimes watching TV shows. I’m a Jennifer Coolidge fan from day one, but TV is one thing I don’t have too much capacity for. But if I am watching TV, it’s a little mundane, like Love Island (UK). I love the British culture; it’s fun to take in. And if I can, I love to connect with friends and talk and hang out — and hang out with their kids, if they have kids. Kids are brilliantly innocent and carefree, and those are some of the things I do. I also love driving here in L.A., though it’s not an eco-friendly thing to say.