Touring during a worldwide pandemic is tricky. But for the London Symphony Orchestra, travel to the United States has been perilous from the very beginning.

The world-renowned orchestra, which will play six concerts in California over the next two weeks, made its first visit to the U.S. in 1912. The players were set to voyage across the Atlantic in style, having booked passage on the Titanic.

They were no doubt disappointed when the luxury liner’s maiden voyage was postponed for a few weeks, forcing them to take another, less-glamorous vessel, the S.S. Potsdam, so they didn’t miss any engagements.

“The orchestra was still on tour in the States when the Titanic went down,” noted Managing Director Kathryn McDowell. “I think the experience of such a ‘near miss’ has galvanized the LSO ever since.”

Whether the current-day culture of an orchestra is truly shaped by a near-death experience a century ago is a matter of conjecture. But whatever the impetus, the LSO has a reputation for not resting on its laurels — or, for that matter, resting much at all.

“The LSO is considered the hardest-working orchestra in the world,” said Scott Reed, president of the Music Academy of the West. “They perform a lot — quite a bit more than some orchestras in the United States.”

Reed has seen this work ethic firsthand. For the past four years, the LSO has partnered with the Music Academy, and that relationship will culminate with a five-day stay in Santa Barbara that will serve as the centerpiece of its tour, and kick off the Music Academy’s 75th season.

Music Director Simon Rattle will conduct three concerts: A Bartók/Sibelius program the symphony will also play in Berkeley and Costa Mesa; a family concert; and a special performance of Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony in which 36 recent Music Academy alumni will play alongside the full-time members.

“We’re building a stage extension to fit everyone into the Granada Theatre,” Reed revealed. “It’s complicated, but these are complicated times.”

Indeed so. This will be the LSO’s first tour outside of Europe since the pandemic shut everything down in March 2020, just after its initial visit to Santa Barbara. It did perform in France and Germany this past September and October, and in the process learned some valuable lessons about making music during the time of COVID.

“We’ve been taking care since the very early days, and then gradually applying what we’ve learned to the travel,” said McDowell, who has served as managing director of the orchestra since 2005. “We take into account what the local regulations are. In some places, you have to wear a stronger mask. In some places, you have to observe distancing. We have a great operational team that is on top of all of those things.

“We are going into different people’s theaters, and we want to keep everyone safe — all the backstage staff. Everyone is double-vaccinated and boosted.”

And if there is a breakthrough case? “We worked out a plan for what we do if someone tests positive on tour,” she said. “They have to remain in a place after the orchestra has moved on.’”

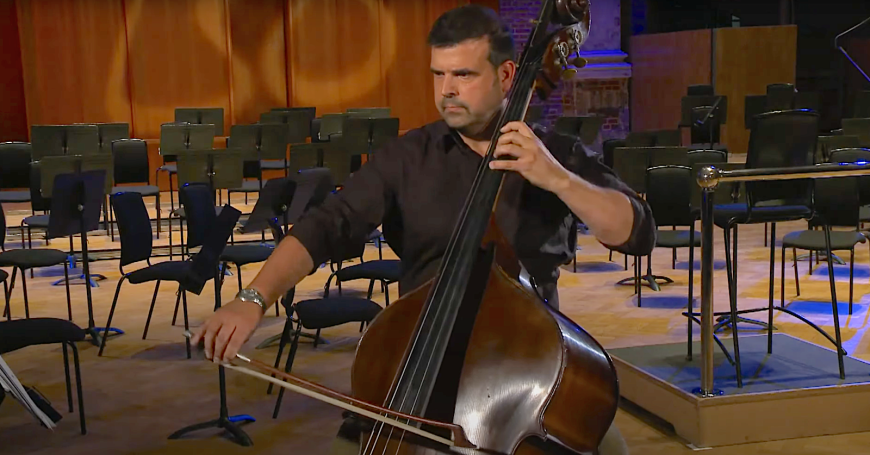

Matthew Gibson knows this from firsthand experience. The double bassist, who has been with the LSO since 1992, tested positive for COVID-19 while on tour in Germany and had to stay in a hotel room for seven days.

He called the experience “not wholly unpleasant,” adding that he is more frustrated by the requirement to wear a mask while performing. “It is the equivalent of asking rugby players to wear masks while running round a pitch,” he said.

If something similar happens on this tour — well, getting stuck in Santa Barbara isn’t the worst imaginable fate. But how does that work for the orchestra? “When we travel, we bring double principals — two first oboes, two first flutes, etc.,” McDowell explained. So a good deal of redundancy “is sort of built in.”

That sort of nimbleness impressed Reed during the pandemic, when many planned collaborations had to be postponed or modified. He reports such adjustments were made with a minimum of friction. “They were game for anything,” he said, “and they delivered at a very high level of quality.”

That same description applies to the orchestra’s music-making. Reviewing a recent Rattle performance of Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony, critic Martin Kettle of The Guardian wrote that “the LSO played with searing commitment and a genuine bloom to their sound.”

“It’s a cohesive sound — sophisticated, incredibly musical, nuanced when they need to be,” Reed agreed. He has observed that, by the end of the first rehearsal, they have the notes down, which gives them time and space in subsequent rehearsals to delve deeply into the emotional core of the music.

To Gibson, “The LSO has a bright and immediate sound, some say formed by the high number of American conductors (André Previn, Leonard Bernstein, and Michael Tilson Thomas).” McDowell, who recalls watching the orchestra on television as she was growing up in Ireland, argues the musicians deliver “a particularly virtuosic type of playing — real panache. The LSO can deliver a piece like the Bartók Miraculous Mandarin in an incredibly dynamic and exciting way.”

A Bartók ballet isn’t typical touring fare for most orchestras; the general tendency is to stick with warhorses. The LSO has gone in an entirely different direction: Its main touring program features that piece, along with Sibelius’s lesser-known Seventh Symphony, short showpieces by Berlioz and Ravel, and The Spark Catchers by Hannah Kendall, a British composer of Guyanan descent.

McDowell called the latter work, which premiered at the BBC Proms in 2017, “a brilliant opener. It’s great to be playing a work from a female composer — someone who has a lot to say.” Its inclusion also reflects the fact that, like so many American orchestras, the LSO is incorporating more works by composers of color into its programs; its Stanford University concert includes George Walker’s Lilacs alongside works by Dvořák and Schumann.

A combination of nearly-new and not-particularly-well-known music “is very much a typical LSO program, especially under Simon Rattle,” McDowell said. “We feel that if we play less well-known repertoire with complete conviction, at the very highest standard, audiences will be taken with it.”

After six seasons with the orchestra, Rattle will be moving on at the end of the 2022–2023 season to take over the Bavarian Radio Symphony in Munich. While some British commentators blamed Brexit for his decision, he insists it is strictly personal — a desire to live closer to his wife and school-age children in Germany.

Gibson will miss him very much, noting “He has an acutely developed sense of musical architecture and, to put it plainly, this makes you feel confident in what you are doing.” But he fully expects incoming music director Antonio Pappano to continue the orchestra’s tradition of maintaining a wide-ranging repertoire.

Two other things are also unlikely to change: The LSO’s busy recording schedule — its archivist estimates it has made around 3,000 recordings since its founding in 1904, including more than 200 on its in-house LSO Live label — and its status as orchestra of choice for countless film composers. The orchestra has been recording soundtracks since 1935’s Things to Come; more recent titles include Alexandre Desplat’s score for the Oscar-winning The Shape of Water, as well as the Harry Potter franchise.

“Many a happy hour I have spent in Abbey Road studios, notably with John Williams recording the Star Wars films,” Gibson said. “Apparently John Williams coming over was something to do with him being a friend of André Previn, who had recently taken the job in London and he recommended the LSO to John. So the story goes.

“We have become the orchestra of choice for film work for a number of reasons: We are very quick sight readers, we have a flexible schedule and we have that brilliant and direct sound when it is required,” he added. “Also it has a lot to do with the fact that we are much cheaper than Los Angeles musicians because we don't take royalties.”

Whatever the reason, this legacy means the LSO is, in all probability, the orchestra most people in the world have heard — whether they realize it or not. Ironically, though, there is one iconic soundtrack the orchestra was not involved with.

It does not play a note of Titanic.

Look for the London Symphony in California:

March 19 — Bing Concert Hall at Stanford University at 7:30 p.m.

March 20 — Zellerbach Hall at UC Berkeley at 3 p.m.

March 22 — Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa at 8 p.m.

March 24 — Santa Barbara’s Granada Theatre at 8 p.m.

March 24 — Santa Barbara’s Granada Theatre at 7:30 p.m.

March 26 — Santa Barbara’s Granada Theatre at 4 p.m.

March 27 — Santa Barbara’s Granada Theatre at 7 p.m.

For more information on the orchestra and its history, go to https://lso.co.uk/orchestra/history.html.

For more on its partnership with the Music Academy, go to https://www.musicacademy.org/lso/.