If you were creating a playlist with the goal of conveying a sense of what it means to be human to an alien civilization, what music would you choose?

NASA faced that very question in the late 1970s, when it decided to include an audio disc on two probes it sent into deep space. The Voyager spacecraft’s “golden record,” both copies of which are now well beyond our solar system, includes everything from traditional ceremonial chants to Chuck Berry’s rollicking “Johnny B. Goode.”

It concludes on a distinctly poignant note, with the Cavatina from Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 13 in B-flat Major, Op. 130. Nearly a half century later, that intense, aching music seems like a perfect calling card for our flawed, fragile species.

If you want to know — really know — what it feels like to be a human being, there’s no better way than listening to Beethoven’s remarkable set of 16 string quartets and that profoundly sad movement in particular.

“Even in rehearsal, it gives me goose bumps,” said Jeffrey Myers, first violinist of the Calidore String Quartet, which will perform the entire cycle as the centerpiece of this year’s Music@Menlo Chamber Music Festival, July 14 – Aug. 5. “Beethoven is sharing his deepest thoughts and most intimate feelings. That’s the most vulnerable thing you can do.”

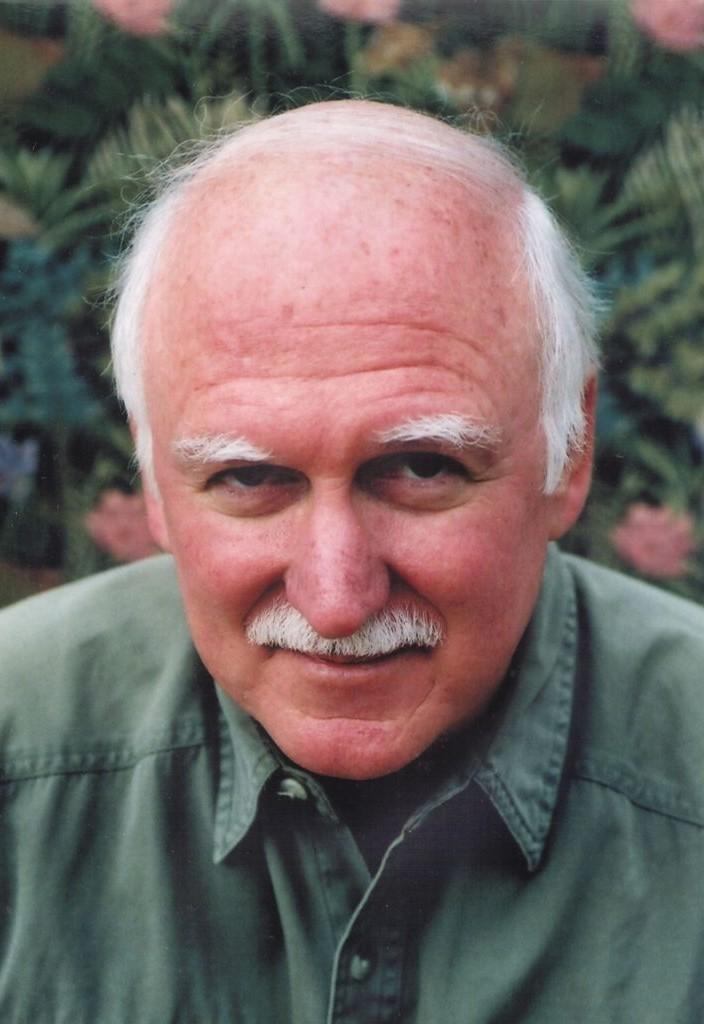

At various times in the cycle — and especially in that Cavatina movement — the composer “bares his soul, writing music so private you almost feel embarrassed listening to it,” agreed David Finckel, the festival’s co-artistic director. While Bach and Mozart can come across as ethereally beautiful, he noted, “Beethoven’s music is so human and so tied to our own reality. There’s nothing like it.”

Finckel knows this miraculous music better than most. As the longtime cellist of the Emerson String Quartet, he played the Beethoven cycle on numerous occasions and made one of the most acclaimed recordings of the complete set.

Since his retirement from that ensemble, he has made it a point to facilitate performances of these pieces — a goal he is in a unique position to accomplish. With his wife, pianist Wu Han, he is co-artistic director of both New York’s Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center and Music@Menlo.

The couple presented the entire cycle during their third year at Menlo, in 2005, and — later than they’d ideally like — they are returning to it this summer. The performers are the relatively young Calidore Quartet, which was formed at Los Angeles’ Colburn School in 2010 and which Finckel has been informally mentoring for years.

The performances are sold out, although tickets are available for the livestreams. Such popularity, at a time when so many arts organizations are having trouble enticing patrons back to the concert hall, suggests audiences think of hearing the entire set over a few weeks as a uniquely enriching experience.

Finckel and Myers certainly feel that way, as does Beethoven biographer Jan Swafford, who will be giving a talk at the festival on July 14.

“There’s no artist who ever lived who had a wider and deeper creative journey than Beethoven,” he said. “The quartets track every bit of that. Hearing them in order is a very good idea; it’s like viewing a comprehensive museum show of a great artist. To see someone go through the changes of their career is fascinating, and that’s certainly true of Beethoven.”

Finckel agreed. “There is no other cycle of pieces like this, except perhaps Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas,” he said. “They span his creative life and document his artistic evolution.

“Beethoven, in the time he wrote these quartets — 1798 through 1826 — not only dominated the world of classical music the way no single composer did before or again. He also changed what classical music was.”

The Beethoven quartets fall neatly into three periods. The first six are classically poised, a comfortable fit with the music of Mozart and Haydn, the latter Beethoven’s teacher for a time. The next five, fiery and dramatic, reflect the revolutionary aesthetics of Beethoven’s Third, Fifth, and Sixth Symphonies. The final five move into an entirely different realm, evolving in unexpected, sometimes startling ways and foreshadowing the 20th century.

“In early and middle Beethoven, the pieces have a discernible implied narrative,” Swafford said. “The Fifth Symphony goes from darkness to light. Beethoven seemed to be telling a unified story, albeit this was usually implied rather than specific.

“In the late music, he moved toward something else — what I call his poetic style. Rather than a narrative that holds the whole piece together, many different moods and feelings can be implied in a single movement. There’s more of a surface capriciousness, which, under the surface, isn’t capricious at all.

“Meanwhile, his harmonic style became more elusive. The harmonies got more complex at times. He got more contrapuntal. He turned to a great interest in Baroque genres like the fugue, but he takes that idea into his own time, in his own voice.”

Finckel describes the quartets in similar terms. “Beethoven was able to take from the past — sometime the distant past — but he wrote music of the future,” he said. “I don’t know how he did it. The Grosse Fuge [part of the quartet cycle] sometimes sounds like [Igor] Stravinsky.

“There are no two movements in these 16 quartets that are like each other. Every piece is a completely fresh idea. It seems impossible for one person to have generated that much artistic variety. But Beethoven had that kind of mind.”

Along with opening up a far wider range of artistic expression, the quartets also mark a different kind of dramatic shift. “They trace a sea change in the business of classical music — the way it was performed, the way it was presented, the way it was listened to, and the way composers were regarded,” Finckel noted. “They went from largely being thought of as servants or suppliers of entertainment to being autonomous artists.”

Prior to Beethoven’s time, “string quartets were basically an amateur medium,” said Swafford. “They were played in private music rooms and at private concerts.” In contrast, nearly all of Beethoven’s quartets were premiered by an ensemble led by violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh, “who was basically the first person in Europe to make his reputation as a chamber music player. He had the first standing professional quartet.”

Beethoven and Schuppanzigh’s relationship was mutually beneficial. The violinist, who organized what may be the first-ever subscription series of chamber music concerts, was given exciting new works that audiences wanted to hear. For his part, Beethoven “had the best quartet in the world at his disposal. That inspired the Op. 59s and the rest of his quartets.”

Two centuries later, these pieces are still uniquely challenging to play. Beethoven, Swafford noted, was “an extremely capricious person. He had a terrific temper. He could get very angry very quickly. But if he felt that he wronged somebody, he could get abjectly apologetic. He was at the mercy of enormous emotions, and I think that was true when he composed.”

Especially in the late quartets, that volatility comes across in sudden, dramatic mood shifts, which present considerable challenges, according to Myers. “To be able to physically make that quick change is something you have to learn how to do,” he said.

“Going from soft to loud is one problem, but going from loud to soft — to really cool your emotions — is very physically demanding in a different way. You have to train your muscles and figure out how to make it work, individually and together. We’ve developed different exercises and rehearsal techniques to try to figure that out.

“I’m reminded of a story that Earl Carlyss, second violinist of the Juilliard Quartet, told us. He said you might feel you’ve got the quartets under your belt, but whenever you return to them, Beethoven has his thumb on your throat, and he never lets go. I didn’t understand it at the time, but now I do.”

Finckel expressed similar thoughts as he described performing the Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp Minor, Op. 131, his favorite of the set. “It has every emotion, every mood, everything you could ever want in music — and it’s one of the most physically difficult to play,” he said. “It’s very tough on the left hand. He shows no mercy, jumping around, leaping registers. It’s exhilarating to work that hard and so rewarding at the end.”

Like the great 20th-century quartets of Dmitri Shostakovich, Beethoven’s quartets are not infrequently described as autobiographical. The playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw called Beethoven the first composer to express his own life in music.

Swafford agrees with that comment “about halfway. Mozart was writing about his emotional life, but he didn’t consider his music to be about himself.

“The idea that art comes out of the personality and sometimes expresses the demons of the artist is a 19th-century idea. The Romantics seized on that quality in Beethoven. Whether he considered his music that way or not, I don’t know.

“I don’t know if he said to himself, ‘I’m going to write out of my anguish,’ but I don’t think artists do much of that anyway. It’s more that they get an idea, and you use what you understand and instinctively, emotionally feel to realize that idea. [It’s quite possible] he didn’t set out to express his inner suffering. He intuitively used that to create such touching slow movements.”

Touching — but never cloying. “There’s no self-pity,” Finckel noted. “You don’t hear him feeling sorry for himself. Maybe for all of mankind, but not for himself personally.”

While acknowledging that suffering, Swafford cautioned against viewing Beethoven as an anguished, tragic figure. He sees that as, at best, an oversimplification.

“The idea of Beethoven the scowling genius came from this guy who made a life mask of him,” he said. “Beethoven was scowling because he had three inches of gypsum on his face and a straw stuck up his nose to breathe.

“People who knew him said his usual expression was quite passive. Also remember, Beethoven wrote some delightful, funny music in his last period.”

Indeed, the idea of Beethoven as a one-dimensional tragic hero is upended by the final quartet, No. 16 in F Major, Op. 135, which includes one of those sublime slow movements but concludes with a surprisingly jaunty, dance-like finale.

“The word I use to describe it is ‘wistful,’” said Finckel. “It’s philosophical. It’s lighthearted in some ways. It’s a very sophisticated piece with an almost childlike facade.”

“The C-sharp Minor Quartet [Op. 131] is one of the most tragic pieces every written, and there are about 600 pages of sketches for the first movement,” noted Swafford. “It took a lot out of him. I think with Op. 135, he thought, ‘This is going to be my last quartet, at least for a while. I just want to have fun with it.’”

Given this complexity and variety, it’s no surprise that musicians find new things in these quartets when they return to them. That was certainly Finckel’s experience over the decades; perhaps surprisingly, it’s also Myers’s, even though the Calidore has only been playing the full cycle since 2019.

“We’ve recorded all of them,” he noted. “The late quartets, which came out earlier this year, were mostly recorded over 2021. Listening to them now, I already feel I’m playing aspects of them differently.

“That’s the amazing thing about these quartets. You’re never done learning from them. The experience is constantly changing. That’s what makes it great art.”

Myers recalled that both Finckel and Arnold Steinhardt of the Guarneri Quartet, with whom Myers studied at Colburn, advised tackling the Beethoven set early in one’s career rather than waiting.

“[The Calidore Quartet] is perfectly positioned to do this in many ways,” Finckel said. “Besides all being first-class instrumentalists, they have tremendous drive and determination to succeed. They’re in the right place in their careers to be doing this. There’s stuff a young quartet can bring to this music that’s fantastic.

“They’re going to be surrounded by a cauldron of love and admiration, enthusiasm and support, to propel them through this cycle. It takes great energy, determination, and stamina to get through a Beethoven cycle in a few weeks. Menlo is the perfect place to give them that.”

From there, the sky’s the limit.

The Calidore String Quartet will perform the entire Beethoven quartet cycle July 16 – Aug. 3 at the Music@Menlo Chamber Music Festival in Atherton. Finckel will give preconcert talks before each performance. The concerts are sold out, but livestreams are available for home viewing. For more information, go to Music@Menlo’s website.