I first saw James Conlon, then just 29, at the Hollywood Bowl in July 1979 leading the Los Angeles Philharmonic in an intense, precise, triumphant performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 that woke the orchestra up from the summer doldrums. I immediately thought — and wrote — that this guy was going places.

But thereafter, we didn’t see much of him in Southern California, not for decades. Although he had racked up other prestigious domestic gigs by the time he turned 30, his career didn’t really take off until he made Europe his base. He became the principal conductor of the Rotterdam Philharmonic, then the general music director of the city of Cologne, music director of the Cologne Opera and Gürzenich Orchestra, and principal conductor of the Opéra National de Paris.

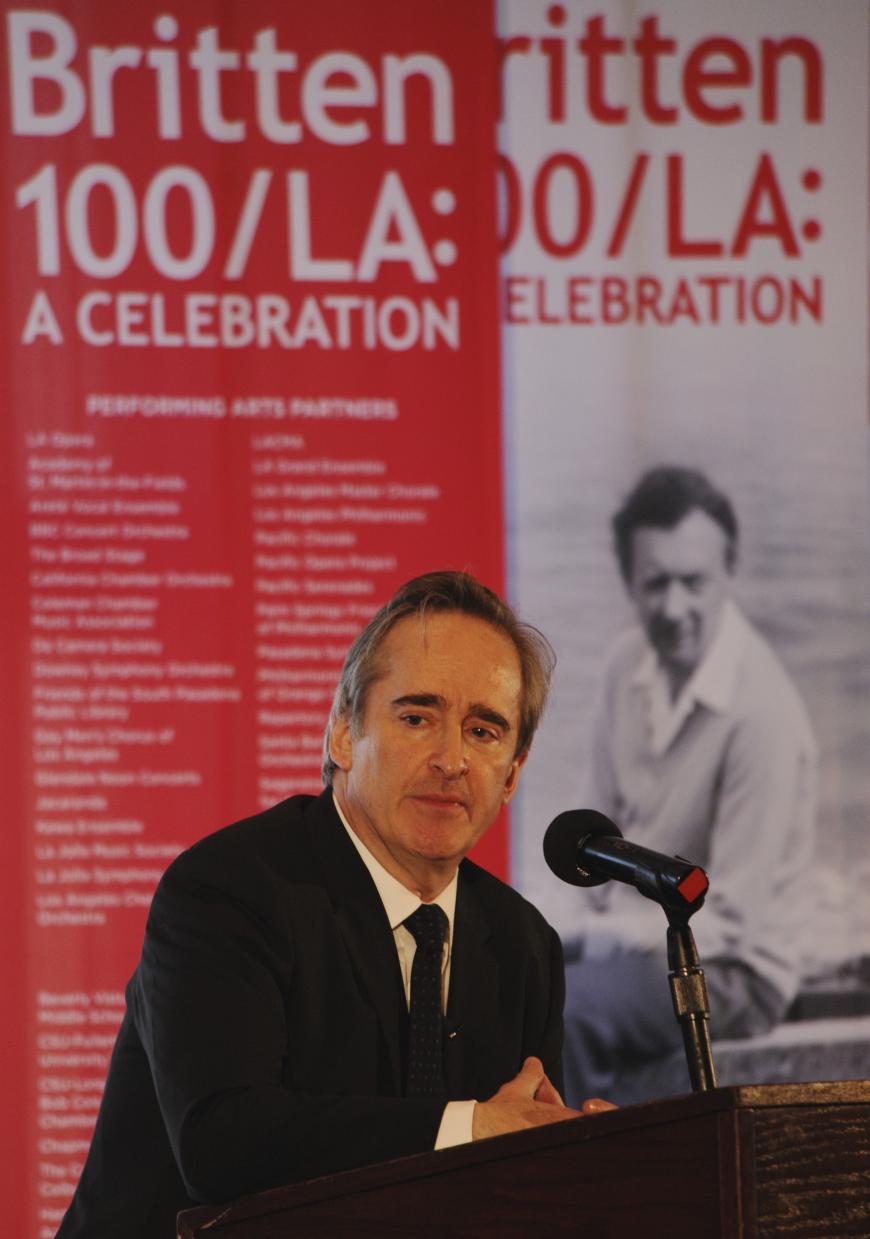

Ultimately, Conlon returned to Los Angeles to stay in 2006 when he succeeded Kent Nagano as music director of LA Opera. Immediately, he took a full hands-on approach. An energetic dynamo, Conlon seemed to be everywhere — conducting operas, doing all of the pre-performance lectures which became entertainingly informative attractions in themselves, speaking about music and other topics across the region, working with young people.

He wanted to stamp LA Opera as a Wagner company — and in 2010 managed to lead the first fully-staged, locally-produced, complete Ring cycle in not only the company’s history but in Southern California, period. There were other enterprising Conlon projects — the “Recovered Voices” Initiative to exhume works by composers who were persecuted by the Nazis and subsequently forgotten, a city-wide festival honoring the centenary of Benjamin Britten in 2013, a “Figaro Unbound” festival in 2015 centered around operas based on the three Beaumarchais Figaro plays.

Eager to get back indoors as the COVID-19 pandemic waned in California, Conlon led LA Opera’s return to its Dorothy Chandler Pavilion main stage June 6 with a stirring performance of Stravinsky’s “waxworks opera,” Oedipus Rex, and he is conducting four productions in the welcome-back 2021–2022 season. Recently, he also found the time to serve as principal conductor of the RAI National Symphony Orchestra of Turin, Italy, and, starting in September, as artistic advisor for the Baltimore Symphony.

While Conlon’s discography has its share of standard repertoire, it is most notable for its extensive selection of “Recovered Voices” pieces — a passion ignited by accident when he heard a broadcast of Alexander von Zemlinsky’s Die Seejungfrau on his car radio while driving home after conducting a performance at Cologne Opera. He went on to record nine albums overflowing with all of the little-known Zemlinsky orchestral, lieder, and choral works, along with three of the eight operas, for EMI Classics. His time at LA Opera also produced several audio and video recordings of “Recovered Voices” rarities.

“When I started recording over 35 years ago, I tried to make a contribution to the world by actually recording things that are under-recorded or not recorded,” Conlon told me during an interview for the Los Angeles Times in 2017. “I’ve never made a recording of a Beethoven symphony or a Brahms symphony. Does the world need another Brahms cycle? Not really.”

Accordingly, you won’t find any of the big Bs in the following selections from Conlon’s catalogue:

Liszt: A Faust Symphony or Dante Symphony — Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra (Erato or Warner Apex, CD, 1983–1984). From 1983 to 1985, while in his early 30s, Conlon took on his first major recording project by surveying a large batch of Liszt, hitting the well-known spots and burrowing deep into little-known corners of the composer’s vast, highly-uneven output. The heftiest release, the oratorio Christus, is currently out of print, but the orchestral discs can still be found, and Conlon gives them the desired high-tension treatment. Of the two symphonies, A Faust Symphony is the stronger piece, but the Dante Symphony disc may be easier to locate.

Zemlinsky: Die Seejungfrau, Sinfonietta — Gürzenich-Orchester Kölner Philharmoniker (EMI or Warner, CD, 1995). Die Seejungfrau — or The Little Mermaid — is the piece that got Conlon started on what looks to be a never-ending “Recovered Voices” journey. It’s a big, voluptuous, three-part, 44-minute tone poem for a gigantic orchestra that dishes out the luxuriant textures as richly as any Richard Strauss showpiece yet in Zemlinsky’s own individual post-Romantic language. Conlon gives it as splashy and passionate a ride as you might wish for. The Sinfonietta, too, is a luxuriant piece about half the length of Seejungfrau, a late work dating, unfortunately, from 1935 and thus considered unfashionable at the time. Available as a single disc or coupled in a bargain-priced two-CD set with three other rare Zemlinsky pieces.

Schulhoff: Symphonies Nos. 2 and 5, Suite for Chamber Orchestra — Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (Capriccio, CD, 2003). Erwin Schulhoff was perhaps the most interesting, freewheeling composer on the “Recovered Voices” roster — and Conlon offers a single-disc seminar as to why. He takes us from one of Schulhoff’s flirtations with imported Prohibition-era jazz in the whimsical Suite for Chamber Orchestra to the mix of neo-classical, jazz, and European folk threads in the lightweight Symphony No. 2. Finally, there is the grim Symphony No. 5, where all of the jazz vanishes and the composer engages in a socialist realism-influenced battle for survival in the face of the 1938 Munich Agreement that doomed his native Czechoslovakia.

Weill/Brecht: Rise And Fall of the City of Mahagonny — Audra McDonald, Patti LuPone, Anthony Dean Griffey, LA Opera Orchestra and Chorus (EuroArts, DVD, 2007). One of the earliest productions of Conlon’s tenure at LA Opera was this rabble-rousing critique of capitalism that Conlon describes as laying somewhere within the triangle of opera, musical theater, and Brechtian alienation theater. If the company’s wealthy donors and prime seat holders were unnerved by the piece’s polemics, they kept it to themselves. John Doyle’s production updates the setting act-by-act from Brecht’s imaginary notion of America in the 1920s to Las Vegas in the 1950s and finally America circa 2007. Conlon’s conducting of Weill’s powerful, hummable score is sharply etched with an authentically tough rhythmic feeling — and he can be frequently seen on camera driving on the pit band and an eclectic cast of singing actors. Also, you get a Conlon discussion of the opera as a bonus feature.

Schreker: Die Gezeichneten — Anja Kampe, Robert Brubaker, LA Opera Orchestra and Chorus (Bridge, 3-CDs, 2010, released 2013). Conlon’s invaluable “Recovered Voices” project at LA Opera yielded five productions on the main stage before the funds ran out, all but one of which were recorded and released. Die Gezeichneten (The stigmatized) was the final, most elaborate production of all, apparently the first time any of Franz Schreker’s operas had been staged in the Western Hemisphere. While the other RV operas received video releases, we only have an audio souvenir of its deliciously overripe, gorgeously orchestrated waves of glistening sound (if not its R-rated Ian Judge-directed visual component), with Kampe conveying the fragility and sexually indecisive nature of Carlotta and Conlon reveling in the orchestral color while cranking up the intensity toward the verismo conclusion.

John Corigliano and William M. Hoffman: The Ghosts of Versailles — Patricia Racette, Christopher Maltman, Lucas Meachem, LA Opera Orchestra and Chorus (Pentatone, 2-SACDs, 2015). This was the centerpiece of LA Opera’s “Figaro Unbound” festival — the first full production of the opera anywhere in two decades and an extravagantly glorious one at that, a peak point in the Conlon era. Corigliano and Hoffman sidestepped the centuries-old problem of forging an opera out of the third part of Beaumarchais’s Figaro trilogy by turning it into an opera-within-an-opera, juxtaposing a ghost world of modern tone clusters and microtones with delightful Mozart/Rossini pastiches and revolution-haunted drama. Conlon particularly relishes the ghost world music while bringing his top game to the buffa episodes. Again, this production was released only in audio form, but it was the first recording of the work in that format. Highly recommended to followers of contemporary opera and to anyone who loves the standard Figaro operas and their characters.

Verdi: Macbeth — Plácido Domingo, Ildebrando D’Arcangelo, Ekaterina Semenchuk, LA Opera Orchestra and Chorus (Sony, 2-DVD or Blu-ray, 2016). This appears to be the only one of Conlon’s several collaborations in Verdi operas with Domingo — his then-boss at LA Opera — that was preserved on a commercial recording. These were the years when Domingo, then 75, was trying to collect as many of the Verdi star baritone roles as he could. The vibrato may be wider and the timbre still that of a tenor, but Domingo’s dramatic instincts as Macbeth are as sharp and charismatic as ever — and Conlon’s incisive grasp of Verdi’s earthy, years-in-the-galley manner keeps the pot boiling. It was a collaboration that can now be called historic (and if it’s politically incorrect to say that in light of what’s happened to Domingo’s career in America since, I’ll take the chance).

James Conlon’s Corner. If you’ve been missing Conlon’s pre-opera lectures as the pandemic locked us in place, this is the next best thing. LA Opera has archived Conlon’s program notes, podcasts, episodes of “Coffee With Conlon” recorded during the pandemic, musings and reflections on past productions, and whatever else seems to cross his mind.