Miuccia Prada, head designer of her eponymous company, once stated, “What you wear is how you present yourself to the world, especially today, when human contacts are so quick. Fashion is instant language.”

Classical music can also be considered “instant language,” especially when performed by the French piano duo Katia and Marielle Labèque, who have been dazzling audiences throughout the world with their musicianship — and couture wardrobe — for more than five decades. Included in their custom-made fashion dossier? Feathered frocks by Prada, which the siblings donned while playing Camille Saint-Saëns’ The Carnival of the Animals for a 2005 televised concert at the Waldbühne with conductor Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic.

“But,” recalled Katia on a WhatsApp call from Sofia, Bulgaria, “fashion was not part of our life at the very beginning. Then the journalist Colombe Pringle from Elle, and later Vogue, came to a concert and thought [we were] cool to play like that. She introduced us to all the great fashion designers of this time in Paris. And they all designed clothes for us.”

Indeed, the sisters, who were born in the Basque country and currently live in Rome, explained that their first designer was Pierre Cardin, who crafted outfits for them for a performance in his theater, Espace Pierre Cardin, in 1970. “He did not want us to play [in] our jeans,” Katia explained, “so he designed two beautiful silk shirts with fluid black pants. That was our first concert in Paris, and Olivier Messiaen was in the hall.”

And so began the Labèques’ foray into fashion, with the crème de la crème of couturiers dressing them in sleek, chic, and timeless garb that would certainly get Anna Wintour’s seal of approval. Add to the sisters’ list such high fashion monikers as Yohji Yamamoto, Jean Paul Gaultier, Gucci, Riccardo Tisci (from his time heading Givenchy), and Issey Miyake, whose plissé (pleated) fabric doesn’t require “a steamer” (iron) when traveling, noted Katia. The Labèques’ indelible image has secured its place in both bespoke and classical music history.

Their garb — and musical chops — will be on view when the siblings join with composers and guitarists Bryce Dessner and David Chalmin to tour the U.S. as the Dream House Quartet. Traveling with radical new commissions from visionary composers, including Radiohead’s Thom Yorke, the musicians land at San Diego’s Epstein Family Amphitheater on April 26, Stanford’s Bing Hall on April 27, Costa Mesa’s Segerstrom Center for the Arts on April 28, and Los Angeles’ Royce Hall on April 30.

But in the grand scheme of things — with many audiences, especially in Southern California, where the surfer/skateboard look can show up in the opera house — how important is concert garb for the stage, and how important is it for artists to establish, in today’s parlance, a brand?

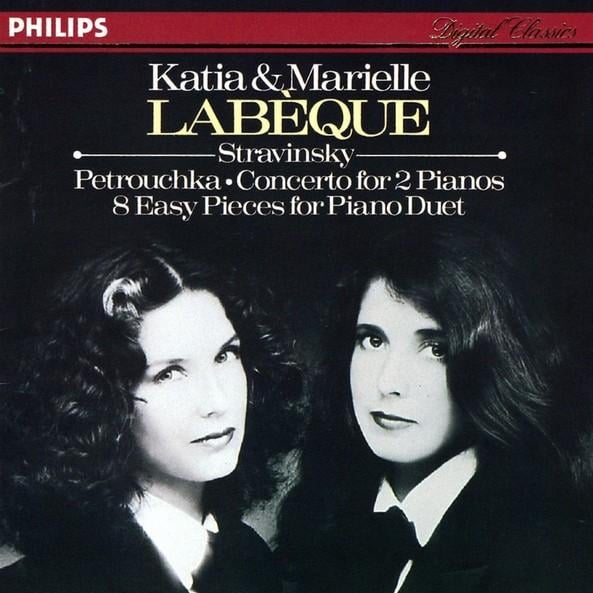

For the Labèques, who donned Yves Saint Laurent’s smoking jackets and bow ties for the cover of an early Philips recording of Stravinsky works, performance attire not only helps define their image but also depends on what repertory they’re playing. (This idea brings to mind a dictum by the late couturier Karl Lagerfeld, who once said, “Fashion and music are the same because music expresses its period, too.”)

Explained Katia: “If we play very modern stuff, we like to be in jackets. But we ended a tour with [the ensemble Il Giardino] Armonico, [who play] Baroque instruments, wearing amazing silk Baroque jackets that Romeo Gigli made years ago for us. If it’s open-air or if it’s cold inside — I was always cold, even when I was 20 years old, and I never played with bare arms — we play with long sleeves.”

One special occasion was in 2016 for the Vienna Philharmonic’s Summer Night Concert on the grounds of Schönbrunn Palace, an annual offering that draws tens of thousands of people. Performing with the orchestra, which was conducted by Marielle’s husband, Semyon Bychkov, the sisters were clad in Tisci’s finest, with Katia commenting, “You can see Riccardo’s dresses with 500,000 multicolored paillettes, and each paillette was done by hand.”

But dresses aren’t the norm for the Labèques, and with Marielle a tad taller than Katia, they can’t exchange clothes. “I like that we are different physically,” pointed out Marielle, who was born in 1952 and is two years younger than her sibling. “And we should not wear the same stuff. We like to keep the same style, to wear something similar but not exactly the same.

“It’s not so easy to wear things onstage and also sit down,” explained Marielle. “If you’re a singer or violinist, OK, but when you have to sit on the dress, it’s not very nice, so I prefer to have a jacket that goes around the chair. It’s more elegant. I wore the dress with the paillettes, though,” she added with a laugh, “and I counted all of them, to be sure.”

As for footwear, Katia admits to wearing “very high heels, but mostly platforms, not stilettos or anything higher than Yuja [Wang’s] heels, so you don’t see it. The one who was [always] wearing high heels, because she was so small, was [Spanish pianist and composer] Alicia de Larrocha. I always wore high heels, Louboutin, of course, but more the boots than the stiletto.”

Ah, oui! French-born cobbler Christian Louboutin is the go-to garcon for a woman of means, as well as any virtuoso daring enough not only to master the teetering walk onstage but also to perform in heels as thin as a toothpick and as high as a Carnegie Deli corned beef on rye. Setting up shop in 1991, Louboutin raised the footwear bar, literally, with his heels incorporating his signature shiny red-lacquered soles. And while Yuja, the megastar keyboardist who was born in 1987, wouldn’t begin wearing the coveted brand until somewhat later in her career, today’s audiences — in person and on social media — can’t help but comment on her sense of style.

After all, it was the late designer Sonia Rykiel who once said, “How can you live the high life if you do not wear the high heels?”

And true to form, Yuja wore a selection of her beloved shoes and an array of eye-catching gowns when she performed all five of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s scores for piano and orchestra over a span of two weeks in February with conductor Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Of those concerts, the Los Angeles Times’ Mark Swed wrote that she played “with exceptional power, depth, and dazzle.” (Yuja’s recording of the Variation 18 from Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini has just been released on Deutsche Grammophon.)

In a conversation with SF Classical Voice early last year, Yuja was effusive about her Louboutins but not so much Manolo Blahniks, the shoe of choice for Sarah Jessica Parker’s character Carrie Bradshaw in the erstwhile TV show Sex and the City.

“Blahniks are great, they’re just not high enough,” said Yuja in all seriousness. “Louboutins are very high and very skinny, and I think that’s extremely hot. I have very small feet, and Louboutin is the only one, I think, that makes a 34. I [once] got this question, ‘What are you going to do when you’re 35 and you’re not hot anymore.’ I said, ‘Define hot first.’”

Yuja’s gowns certainly meet the “hot” quotient. Ranging from form-fitting mermaid-length numbers and body-hugging micro-minis to dresses both short and long that feature slits and trains — many adorned with sequins — they haven’t disappointed over the years. In a 2016 New Yorker profile, Janet Malcolm wrote that Yuja, who appeared bareback in a dress with thin crossed straps, “looked like a dominatrix or a lion tamer’s assistant. She had come to tame the beast of a piece [Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier” Sonata], this half-naked woman in sadistic high heels. Take that, and that, Beethoven!”

One wonders if the sartorially splendid Yuja knew of Mary Quant, who recently died in London at 93 and made the miniskirt de rigueur, along with her signature bob. The pianist, with her outré dresses and short, uber-styled haircut, could have easily fit in with the Quant crowd back in the swinging ’60s.

But as COVID restrictions started to ease, Yuja, who said she wore pajamas at home for the first two years of the pandemic, explained that, for her, “a dress is like such a different question. The hardest part now to go on a trip is, ‘What do I put in a suitcase?’ Back then it was so automatic. I was much more efficient — once you’re on that road, on that drive — but now it’s hard to choose.”

Choosing concert attire isn’t difficult for superstar organist and composer Cameron Carpenter, who was the first organist to be nominated for a Grammy Award for his solo album Revolutionary. And while Mark Twain once said, “Clothes make the man,” it was Carpenter who was literally making his own clothes. Dressed like an advertisement for Swarovski crystals, the musician both designed and sewed his shimmering shirts using a mannequin, the start of a look he would finish off with shimmery skin-tight pants and jewel-encrusted heeled shoes.

But now, the 42-year-old Berlin-based musician, who was born in Pennsylvania and homeschooled before earning degrees from The Juilliard School, prefers simpler, more austere attire. In a WhatsApp call from Berlin, Carpenter explained that he had never been interested in fashion but admired the “history of fashion. When I lived in New York in the 2000s, I had an infatuation with fashion and happened to be taken under the wing of Mary McFadden [known for her patented “Marii” pleating], who took me to parties every night.

“Back in the old days when I made my own clothes,” added Carpenter, “that was sort of a misplaced admiration for designers — misplaced in the sense that I never should have been spending time on that. I should have been spending more time on music. That was the influence of living in New York, and it was there that I came into my own.”

Carpenter, once described by The New York Times’ Anthony Tommasini as combining “a punkish persona with tremendous skills,” also had an alter ego at that time, one Shane Turquoise. “That was something that existed in New York because of the club scene,” the organist said, “being in New York in my 20s and stuff. It was a fondly remembered period of my life. I was also friends with a number of amazing drag queens and people who influenced me back then.”

Carpenter moved to Berlin in in 2011, but it wasn’t until a few years before the pandemic began that, he explained, “his sense of personal expression began to change. I felt that that was reflected by my more conservative approach onstage.

“A person also changes as they age,” he added, “or should. Onstage right now, I wear a simple suit from Issey Miyake, his famous pleated polyester blended material, which is not unlike the polyester crepe de chine invented by McFadden, and he would have been influenced by her. That,” he noted, “was a practical solution, [and because] I prefer to be somewhat more discreet, from an engineering standpoint it’s fantastic because it can be rolled into a very small size and I can pack it.”

Carpenter, who closed his social media accounts during COVID, noted that his musical values also changed at that time, when he suffered a huge artistic loss in the form of his International Touring Organ (ITO). The world-class mobile, digitized organ that he designed had become too expensive to maintain. “I also felt it more fitting to appreciate the small patch of ground I had in the musical community and not make such a loud noise about myself.”

For Los Angeles-based designer Karolyn Kiisel, who taught in the fashion department of Otis College of Art and Design for more than two decades and is the author of Draping: The Complete Course, her work doesn’t call attention to itself so much as it reflects a director’s vision and the stage it’s on.

And while Kiisel isn’t working on the grand scale of, say, Los Angeles Opera, where in-demand designer Christian Lacroix recently outfitted the cast of The Marriage of Figaro, she has frequently worked with Peter Wing Healey’s Mesopotamian Opera and was called upon to create attire for his 2022 opus The Tree. Working with a team of 10, she was tasked with conceiving costumes for a cast of 18 and several extras.

“They had three changes,” Kiisel recalled, “and we built 12 tree costumes and four or five evening gowns for a party scene, and one was for a trans guy who was quite big. It was a beautifully draped, asymmetrical silk wool dress, and he told me he felt beautiful for the first time.”

Kiisel, in collaboration with her students, has also made clothes for several musicians of the Burbank Philharmonic Orchestra, including cellist Lisa Belding and French hornist Jean Marinelli. Kiisel said that she had her charges “think about the cellist with her legs positioned and having enough fullness in the skirt to accommodate them and yet look graceful on stage.

“The fabrics,” added Kiisel, “were Jean’s from a repurposed vintage kimono. In the case of a violinist,” she acknowledged, “there are the problems of the armhole and the sleeves. It has to look graceful and in sync with the rest of the garment. You have to have a high armhole to have a lot of movement, and often high armholes are out of proportion with the rest of the garment. To get the lift you need is a tricky balance. It takes a lot of skill.”

In 2006, Kiisel applied her expertise to designing gowns for the women of the Los Angeles Master Chorale, the second resident company in Walt Disney Concert Hall. “The hall was so beautiful and warm. I tried to design with shapes I thought would complement the architecture and interiors of the building, so I started sketching with Gehry sweeps and swirls.”

Kiisel explained that she also needed to take into consideration sizing — “something,” she said, “that looked good on size 2 and 24X.” She also wanted to add a bit of Hollywood oomph, giving the gals “a vintage 1940s kind of look with elevated shoulder pads. I added golden Swarovski crystals on the neckline and the skirt drape, bringing in the golden aspects of the interior, and they wore them for about 10 years. That was a fun venue to design for, and I thought they looked really good onstage.”

Someone who always looks good onstage is the Ukrainian-born, Finland-based conductor and activist Dalia Stasevska. In a Zoom call from Montreal ahead of her debut with the San Francisco Symphony this week, she said that she thinks women are currently “in a nice place” regarding fashion when mounting the podium.

“It’s not this kind of strict formality anymore. It’s disappearing. I’m lucky to have a Finnish designer friend, Klaus Haapaniemi, who makes a kimono, basically,” Stasevska said, adding that “you want to feel comfortable, you want to look great, and you’re a performer. I also like to support my country.”

Having a look is decidedly part of the performance package these days. As Carpenter said, “The live performance is what makes classical music an experience for folks to enjoy. For people who aren’t aware or initiated, the live factor is key, and it’s about what happens in person.

“There’s something there that can’t be reproduced,” continued the organist. “I expect something in person. That’s why some folks who are interested in fashion, if you’re that artistic in a live experience, as Yuja is in her recitals, it adds something to a night to have a nice gown, a presentation, to do it at the level Yuja does.”

And while not every musical artist takes risks — in their repertory or their apparel choices, be they prét-à-porter or the hautest of haute — it’s great for audiences to take in a performance visually as well as aurally. As Carpenter admitted, “All classical music is entertainment. It doesn’t lessen it to say that, [even] if some object to that.”