Alina Cojocaru as Giselle — with her exquisite line, gorgeous extensions, and airy jumps, all rendered with a spectral, buoyant quality — has owned the role since becoming a Royal Ballet principal dancer in 2001. Seeing her perform a pas de deux with a, well, fly may seem jarring at first. But in the digital short “Between the Rooms,” one of 11 films commissioned and produced by Los Angeles Opera when COVID shut down live performances in 2020, Cojocaru is as haunting and stunning as ever.

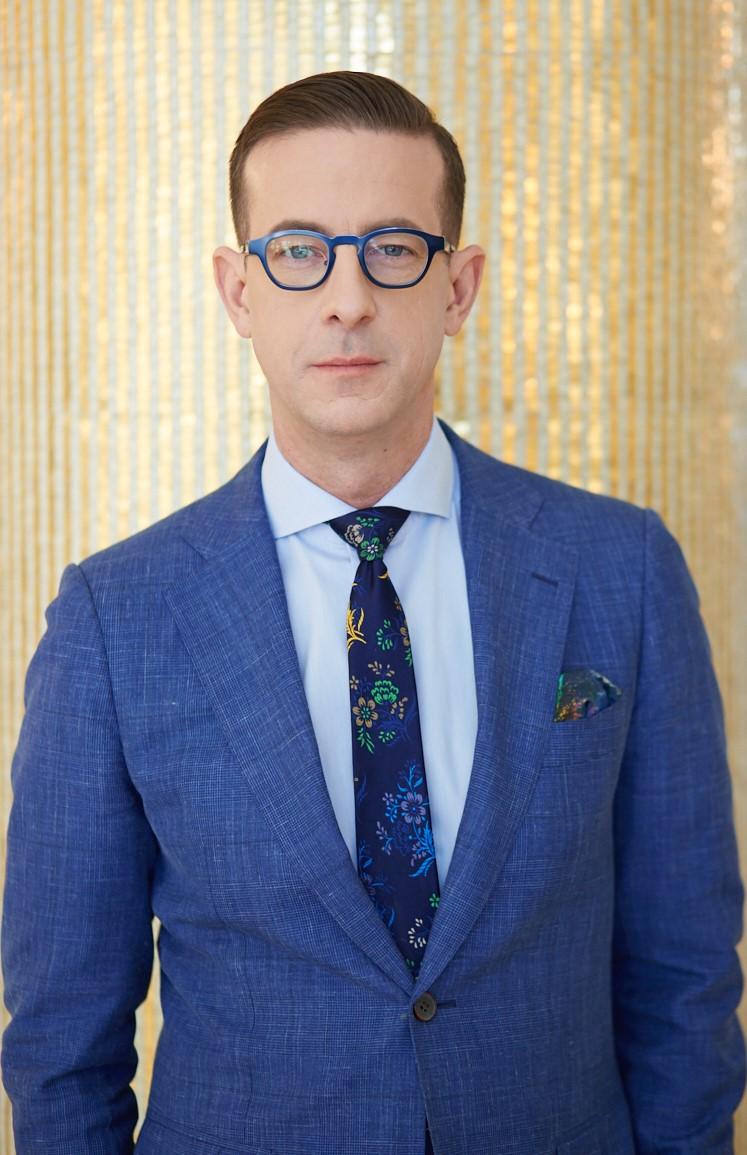

Premiering last May, the nine-minute film features evocative music by London-born, Grammy-nominated composer Anna Clyne (whose This Midnight Hour will be performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic April 21–23) and weaves together three poems by Emily Dickinson. With direction, choreography, and editing by Kim Brandstrup, the short also features another Royal Ballet principal, Matthew Ball. This intriguing piece of art, and the other brief films (all are still available online), were the brainchildren of LA Opera’s president and chief executive officer, Christopher Koelsch.

“To be frank,” Koelsch explained, “these digital shorts were born out of the pandemic and desperation. When I tried to put myself in that terrible mindset, what I was trying to do within the boundaries of things, the conversation, or the idea started because I was thinking [about] how artists could be made to get meaningful work and to reflect the state of the world but to do so in basic isolation, which is,” he added, “a strange way to think about opera.”

Indeed, and when opera, the most collaborative art form, is performed without an audience, the notion seems almost oxymoronic. Koelsch first called Tim Johnson, a DreamWorks Animation director (Antz, Over the Hedge), to investigate a theory he had. “I asked him, ‘Would it be possible to have animators who could work in isolation if I started to commission new work or repurpose extant work?’

“That led to ‘The Zolle Suite’ [excerpts from Du Yun’s 2005 opera],” Koelsch continued. “The process of animation is so labor intensive, but out of that was born the idea of the possibility, again, of creating — maintaining a connection to our audiences through a period of indeterminate length but also making sure we were holding up our solemn responsibility to be creative.

“And the beauty of it for me, almost instantaneously, was that I was looking for things we could be optimistic and excited about. There was also a group of composers I knew and admired from other things. And while it seemed like the world had stopped in its tracks, that was the original impetus, and it grew from that.”

With a budget of about $1.5 million, Koelsch said that, in hindsight, that seemed like a bargain. “But at the time, in an era of collapse, we weren’t really sure. The threat genuinely felt existential, but yes, it was an efficient use of [funds]. And when I say that my entire philosophy of trying to move the company through COVID was ‘How can we take on as little long-term damage to the institution and its people as we can along the way?’ we then made choices that were different from a lot of organizations [knowing that the] people most vulnerable were freelance artists.”

The shorts series, which launched in December 2020, features boldface musical and directorial names like Missy Mazzoli, whose 10-minute offering, “The West Is a Land of Infinite Beginnings,” was helmed by director James Darrah, who also co-directed “Lumee’s Dream,” an excerpt from Ellen Reid’s Pulitzer Prize-winning opera prism (Darrah is currently Long Beach Opera’s artistic director and chief creative officer). Another major name in the series is Gabriela Lena Frank, whose contribution, “The Five Moons of Lorca,” has a text by Cuban American playwright Nilo Cruz.

And while each film makes use of a range of subjects — from mystical beings emerging from a New Mexican landscape (Matthew Aucoin’s “Gallup”) to a reflective setting for a Paul Laurence Dunbar poem (Tyshawn Sorey’s “Death”) to a lush paradise representing the Garden of Eden (Ayanna Witter-Johnson’s “Brown Sounds”) — the theme of extreme isolation is inexorably captured in the black-and-white surreal dreaminess and claustrophobia found in “Between the Rooms.”

Reached by phone from his home in London, the Denmark-born Brandstrup said that Clyne talked to him about doing a film based on Dickinson’s poetry. As he’d studied film at the University of Copenhagen and choreography at the London School of Contemporary Dance, where he forged a narrative style more akin to his cinematic training than to classical story ballet or the kineticism of contemporary dance, the director welcomed the opportunity to make a piece for LA Opera.

“It was very interesting,” recalled Brandstrup, whose commissioned works for numerous companies include The Royal Ballet and Les Grands Ballets Canadiens, “because when [Royal Ballet director] Monica Mason had her last season in 2012, I did a piece with [resident choreographer] Wayne McGregor, and I had just heard Anna’s piece Within Her Arms. It was a beautiful [elegy] for her mother.

“We were keen to get her,” Brandstrup continued, “but she couldn’t do it. She and I kept in contact over the years, and when she called me during lockdown, it was the perfect situation. And since we both have been very fond of Emily Dickinson, the idea felt completely natural.”

The trio of Dickinson poems — “I Heard a Fly buzz — when I died,” “I cannot live with You,” and “I died for Beauty — but was scarce,” with fragments from her envelope poems — proved the perfect way to deal with themes of solitude and creativity that resonated with the pandemic-enforced isolation. Dickinson, after all, had spent the last 15 years of her life in one room, writing poetry in complete seclusion.

Brandstrup said that once they’d chosen the poems, Clyne then wrote the music. The score for soprano Joelle Harvey and Brooklyn-based orchestra The Knights, conducted by its artistic director, Eric Jacobsen, features music suffused with melodic fragments and hymn-like statements. To depict the score visually, Brandstrup immediately knew that he wanted Cojocaru, whom he first worked with at The Royal Ballet in 2004 and again in the 2020 film Kiev. The latter, a love letter to Cojocaru’s teachers and set to the Arvo Pärt’s 1976 piece Für Alina, was filmed in the Ukrainian city, where the ballerina studied before joining the Royal.

Explained Brandstrup: “Because Alina would try things and do something full out, I could model and shape the work from how she did it. That felt rare.”

Cojocaru’s artistry is evident throughout “Between the Rooms.” Her face, a study in melancholy, is accentuated by an intense stare that follows a fly’s movements, while her enigmatic countenance reveals a woman living in her own universe, albeit one trying to make sense of the situation. Cojocaru then spots Ball, the camera closing in on his face, further heightening the oppressive nature of the film — what most of us also felt during lockdown.

The performers’ full bodies are rarely shown, with Stephen Standen’s dancerly cinematography capturing the crushing loneliness of the situation. But as the music becomes more agitated, the duo has a brief moment of liberation as Ball lifts Cojocaru overhead before the fly once again makes an entrance to the throbbing, insistent strings of Clyne’s score.

Allowing the creature to crawl over her hand, the ballerina encases it in her palm before bringing it up to her ear, a wisp of a smile visible as the scene fades to black, the insect’s buzzing still audible over the end credits.

Brandstrup acknowledged the subtlety of the pair’s performance. “You can get right up close, and there’s an interior engagement with the material that you can see in their eyes, which makes it wonderful — and makes it appropriate for making films because I [often] find the language of dance is too big for film.”

But what about the third character in the film, and was there a fly wrangler on set?

The director laughed. “We did it ourselves. We caught four flies and had them in a little glass jar. A couple of them escaped, but one we kept, and the secret was that we would just drop a tiny bit of honey on Alina’s finger and that would make it linger. We were all very proud because we didn’t know if we could make it work, and yes,” added Brandstrup, “the fly’s buzzing was enhanced in post-production.”

A voice that wasn’t enhanced in editing was that of soprano Angel Blue, who sang the title role in LA Opera’s production of Tosca last fall. Her exquisite vocalizing is showcased in Pulitzer Prize-winning composer David Lang’s digital short “let me come in,” which premiered in April 2021. Directed by Bill Morrison, whose multimedia work has been featured at performance venues including the Barbican and Walt Disney Concert Hall and who has collaborated with Lang on some six theatrical and musical projects, the 10-minute film is essentially a rumination on love.

As Morrison’s signature process is repurposing deteriorating early 20th-century films, for this project he recovered nitrate film footage from an obscure 1928 German silent film, Pawns of Passion. Starring Olga Chekhova (Tschechowa, in German) and Hans Stüwe, the work is nothing short of stunning. With a sensual libretto, also by Lang and drawn from the Song of Songs, a biblical book narrated by two lovers, the short film was a co-commission from LA Opera and the Fisher Center at Bard College. It also represents Lang and LA Opera’s third production together. (The company premiered his anatomy theater in June 2016, with video design by Morrison, which was followed by the loser in February 2019.)

In addition to Blue’s opulent vocals, the hypnotic score features percussion, viola, and cello, pulling the listener/viewer into an intimate world of desire, with a compelling meeting of lovers playing out in these rediscovered fragments of a bygone silent film — to surprising effect.

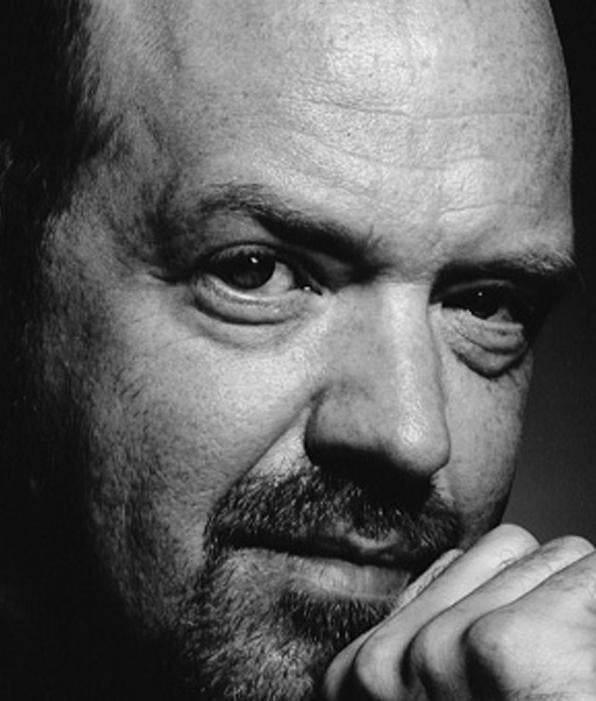

Lang, a professor at the Yale School of Music and co-founder and co-artistic director of New York’s Bang on a Can music collective, recalled the work’s genesis by phone from New York: “As soon as LA Opera called to say they wanted me to do something with video, that was a no-brainer. The next part was trying to figure out what to do. I’d been doing paraphrases of Old Testament texts [since] 2005, and they’re really fun.

“Then I thought of trying to find something from the Song of Songs,” continued Lang, “which I’ve gone back to many times. I had this idea because this text is so purple, and there’s so many different translations that try to hide what’s going on. It’s not actually about people making out — it’s about something else. For this, I just [looked] at all the different translations and, with the magic of the internet, found them side by side.”

There were some 17 different English translations of one Hebrew verse, with Lang ultimately finding “a really powerful one. I thought of when one lover is in the room and the other is on the other side of the door knocking, waiting. There’s a sense of expectation that love, sex, or [something] spiritual is going to happen on the other side of the door.”

Lang went on to say that he took that verse and divided it into phrases before alphabetizing them. “The text ended up being beautiful because of taking this moment in the piece and rotating it around like a prism, the way the light would come through and illuminate different parts of the text. I told Bill that this was what I was going to do, and he got super excited about it.”

The film, with its explosive nitrate blurs, intoxicating in their randomness and akin to a cinematic Rorschach test, could also be a kind of metaphor for the unpredictable and rampant spread of COVID. Add Lang’s spare libretto — “my love was knocking / my lover is knocking / at the door” — which is projected onscreen as supertitles and sung by Blue in a voice ranging from plaintive to poignant, and the work is clearly seductive.

As for Lang’s process, he said that the way in which he organizes and edits the text helps him with his composing. “By the time I’m done figuring out what the text does, I know what the music has to do — it’s the helper to the text. I love doing this,” he added, “and then I let Bill do his thing. One of the things that’s really great when you work with people, you tell them, ‘I’m curious what you’re going to do with this, and I trust you completely,’ and that’s how I hope people will treat me.”

Koelsch also trusts his artists, whether on the mainstage of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion or at smaller, more intimate venues such as The Theatre at Ace Hotel, BroadStage, and REDCAT (Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater), where unconventional works rule. Part of the company’s Contemporary Opera Initiative is its “Off Grand” series, and with its multi-season collaboration with Beth Morrison Projects, the initiative has included such gems as Ellen Reid’s prism (2018) and Du Yun’s 2022 world premiere In Our Daughter’s Eyes.

Coming up at REDCAT April 27–30, is an intense double bill of West Coast premieres, Trade/Mary Motorhead. Composed by Emma O’Halloran, with librettos by the composer’s uncle, actor/writer Mark O’Halloran, the two works depict the down-and-out and the desperate need for connection.

And what is opera if not a means to connect — with artists, audiences, communities, and each other? Says Koelsch, “We made the commitment to ourselves in 2012 to make sure we were committed to not only the preservation of the artform, which is an important part of our duty, but forging the future. That was when ‘Off Grand’ was born, and that there would also be one piece of contemporary music on the mainstage in a season, with the exception of the first COVID year. But that’s part of the commitment we have made to the overall ecosystem.”

With COVID mostly in the rearview mirror, Koelsch is proud of the commitment he made to LA Opera and to the form itself.

“There’s a sense that opera is a very remote art form, that it’s backward-looking and concerned with issues long past, but my proposition is that opera is about the here and the now, and in the [digital shorts] project, we were more able to address that — the injustice, the isolation, the pain. I don’t pretend that any of the short films are operas in any way, but they were a way to respond to the insanity of that moment.”