I began following the English cellist Steven Isserlis on Twitter the first year of the pandemic when his witty and often poignant posts caught my eye. His tweets ranged from homages to dead composers on their birthdays and photos of his cat Macadamia with funny taglines to musings on the meaning of life, sometimes borrowed from Dr. Seuss.

By 2021, the London-based musician had begun touring regularly again, which usually entailed international air travel. Around that time Isserlis began peppering his Twitter feed with restrained rants (imagine Monty Python’s John Cleese as an English aristocrat doling out gracious insults) about airline ticketing snafus that frequently took, and still take, place at Heathrow Airport.

The polite tirades involve the Marquis de Corberon Stradivarius cello of 1726 that he mostly tours with and for which his London travel agent — a booking wizard aptly named Merlin — purchases an adjacent cabin seat, usually in the economy section. Many of those tweets are devoted to British Airways (its hashtag included), which was and remains the primary target of Isserlis’s frustration, despair, anger, and resignation.

There are, however, other airlines and airports that Isserlis has taken to task on Twitter. His tweets about his check-in encounters have ranged from missing boarding passes for the cello, which is ticketed under the name “Cabin Baggage,” to missed flights because of check-in delays to a canceled flight for which Isserlis was rebooked on a later departure but his cello was not.

Federal rules require U.S. air carriers to accept musical instruments on passenger flights as carry-on or checked baggage subject to each airline’s conditions. Some international carriers, such as British Airways and Air Canada, are in line with U.S. policy. Most are not, according to a 2016 International Federation of Musicians ranking of airlines.

Musicians who have experienced flight check-in mishaps with larger instruments, including an airline losing or misplacing an instrument checked as luggage, might take to social media and employ explicit language in response. But not Isserlis. He prefers instead to levy his tweets at the offending airline with elegant grumbles such as “appalling behaviour.”

Before the pandemic, Isserlis frequently took to Facebook to describe the latest episode of what he calls a long-running soap opera in which he frequently co-stars with British Airways and the Stradivarius cello that’s on loan from the Royal Academy of Music (it’s one of five cellos he either owns, co-owns, or has had lent to him). Since the COVID-19 outbreak, however, he has confined the soap opera’s newest plot twists — the good, the bad, and the ugly — to Twitter (he currently has 37,600 followers).

Isserlis also proffers effusive tweets about seamless airline experiences. Between the older Facebook posts and the more recent tweets, he could be compiling an ersatz Gault & Millau of airports and airlines for musicians and their instruments.

First Movement: Let My Cello Fly

In early February, I met with Isserlis in the small art deco lobby of a 1920s-era San Francisco hotel he favors when staying in the Bay Area. A few days later he was to play a series of concerts with Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, which is led by his good friend and fellow Brit Richard Egarr.

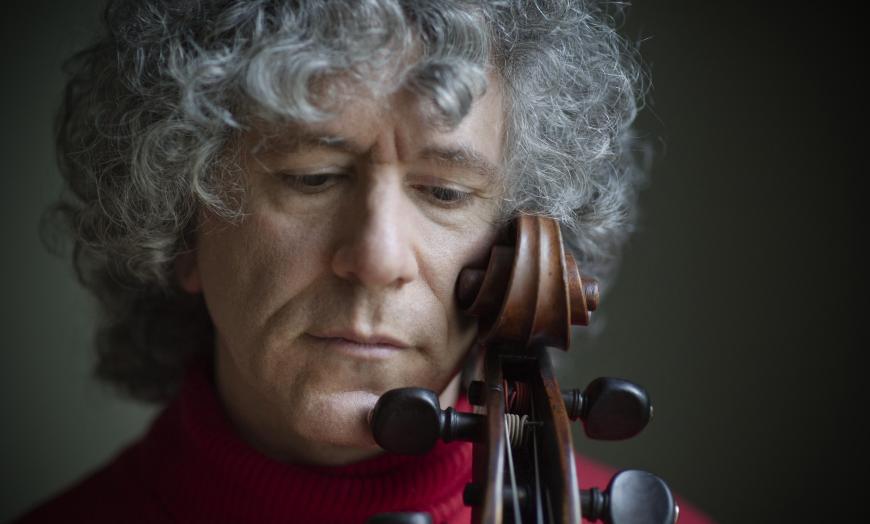

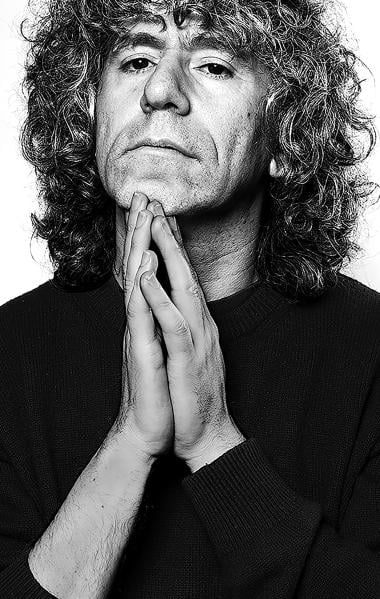

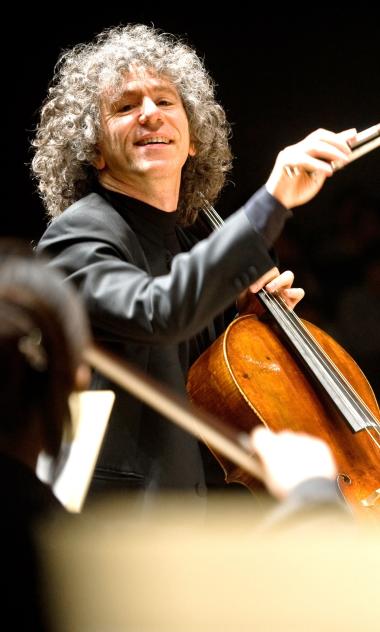

I recognized Isserlis from a publicity photograph that captured him bowing a cello, long curls framing a seraphic face with eyes gazing upward and askew shoulders in contrapposto, a pose suggesting rapture, as in Bernini’s sculpture the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. In person, however, Isserlis seems more MIA from a Tolkien novel. He’s like a taller denizen of Middle-earth (minus the elf ears) with a posh English accent and a penchant for Harpo Marx.

He wore dark dad jeans, a faded black T-shirt, and sneakers that gave him a bouncy stride as we made our way to the teensy lounge area. We sat on facing floral upholstered armchairs barely the width of the narrow hallway that was wedged between the restroom and an open closet doubling as the hotel’s business center. He wore no face mask and remarked how he’d seen more people wearing them in San Francisco than in London. He’s had COVID-19 twice. He was testing the next day for the virus before beginning rehearsals with the orchestra and teaching a master class the following evening.

“That’s like an Escher print,” he said, staring down at the hallway’s vintage linoleum floor, his bright, dark eyes tracing its dizzying grayscale geometric pattern. He had flown in from Zurich a few days earlier after performing and giving master classes in Gstaad. “Nice flight. Went smoothly. Lovely food,” he said with an impish grin, giving high marks to Swissair. He wondered when jet lag would hit. He flies a great deal, as he tours nearly eight months of the year. I asked whether he’d considered his carbon footprint. “I can’t do what I do by Zoom,” he replied, shrugging his shoulders. “It’s the businessmen who can meet by Zoom. That’s where the carbon footprint can be cut.”

I had caught him between a post-dinner break and hours of solo practice later that evening. He’d spent part of the day sitting in on a San Francisco Symphony rehearsal. “It was Blomstedt,” he said with awe, referring to Herbert Blomstedt, the Symphony’s former music director, now 95 years old. Isserlis then pulled a black-ribbed turtleneck sweater over his mop of shoulder-length steel-gray curls that once led him to be mistaken for Queen’s Brian May at a Paul McCartney concert in Tokyo. “It was shortly after that movie came out,” he noted, referring to 2018’s Bohemian Rhapsody.

As we spoke, I learned he has had air-travel challenges with his cello since the last century. In addition to social media posts, he’s also written about the continuing soap opera in the popular press, including a humorous but pointed 2007 essay for The Guardian, “Let My Cello Fly,” that featured British Airways center stage.

In that essay, Isserlis recounted incidents ranging from his claim that a British Airways official threatened (in front of his then-7-year-old son) to have him arrested for not arriving at a gate early enough to another time when he was flying from Heathrow to Geneva, where he was delayed at check-in before learning he’d been charged the wrong price for his cello ticket. Isserlis and his cello were then not allowed to board until he’d paid nearly 10 times as much for the cello seat as for his own ticket, he wrote, noting the airline hadn’t apologized for either incident.

British Airways did not respond to several requests for comment by press time. I reached out to Isserlis in late March to ask whether he or his travel agency American Express had ever filed an official grievance with that airline or with others. “Only when I’ve actually missed the flight because of check-in difficulties,” Isserlis replied in an email. In those cases, British Airways has had to pay the full fares of the replacement flights, he said, “which has led me to wonder why they don’t save money by training their staff properly.”

In a 2014 memo, the U.S. Department of Transportation recommended better training of airport and airline personnel to ensure compliance with current air-travel policies concerning musical instruments. As well, musicians were advised to know each airline’s criteria for flying with musical instruments before booking travel. Instruments brought into the cabin as carry-on items, for example, don’t have priority in overhead bins.

Double bassist Esperanza Spalding rethought her air-travel philosophy after a series of problems flying with her instrument. “Airports can be stressful, people can be awful, you can be delayed and miss stuff,” she told The New York Times in 2019. Her solution is to travel with an electric bass that she checks as luggage: “That overhead bin situation, that makes me stressed out — that thing of ‘am I going to have space for it up there?’ I had to let that go.”

Second Movement: The Routine

Like many performers, Isserlis has a calming ritual he follows before going on stage. For lunch or dinner, he’ll eat red meat, often a hamburger. Then he has a “lie down.” When he gets up, he listens to the Beatles — Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is a favorite. Then 30 minutes before a performance, he drinks a cup of strong black coffee. He began the routine 10 to 15 years ago partly out of superstition. “My father was Russian and superstitious,” he said. It helps to combat a fear of stage fright — that he’ll forget the music while performing, despite hours of daily rehearsal. “Coffee makes a difference,” he told me, “but of course, it’s psychological.”

The 64-year-old also has a ritual of arriving at an airport three hours before his flight — except for when he is late. He never knows how check-in with the cello will roll out. “It really comes down to the individual,” he said, referring to airline counter agents. Usually, his early arrival allows him enough time to obtain boarding passes for both himself and the cello before heading to a special lounge to relax.

He stays in the lounge until he can board his flight earlier than other passengers in order to install his cello on its seat (most airlines require the window seat for a larger instrument so that, in an emergency, another passenger can easily exit the cabin). British Airways holds one seat for a cello on passenger flights, he explained. Different cabin classes on British Airways require the cello’s fingerboard to be placed in various positions. A quick study of that airline’s guide suggests a cross between Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mt. Fuji and a Kama Sutra of cello positions.

Earlier this year, Isserlis arrived at Heathrow three hours before his KLM flight to Amsterdam. In his coat pocket was a note from his travel agent documenting the cello’s cabin-seat ticket as backup in case check-in problems ensued. The way Isserlis tells it, despite his best efforts and a booking procedure followed correctly, the airline wouldn’t let him and his cello on the flight. “I got pretty angry — my good manners last only so long. But my real frustration is that it’s not their fault,” he said of the KLM airline counter and gate agents in that situation.

Isserlis told me he has never missed a performance because of air-travel problems. He’s missed flights, rehearsals, and sleep, however, and has spent more time in airports and money on new tickets than he’d like. I asked whether he’d found a place of equanimity to manage the pitfalls of air travel with his cello, joking that perhaps his frustrations may lead his steel-gray hair to turn white sooner than he’d like, which drew a deep laugh from him.

Then resignation crossed his face. “There’s nothing you can do,” he sighed. He often manages his anger and frustration by tweeting about the incident. “And sometimes,” he said, somewhat sheepishly, “I have temper tantrums. But what can you do? That person in front of you is incompetent, but it’s not their fault. With British Airways, it’s mostly in their booking system. They need to fix it. And it’s airline personnel who don’t know the regulations.”

Third Movement: On the Case

Isserlis hates liver, kidneys, caviar, canned tuna, the music of Frederick Delius, jet lag, and airlines that give him a hard time about his cello. At airports he usually juggles luggage in addition to his instrument, which is nestled in a large, white carbon-fiber case made by Alan Stevenson. “One was in a James Bond film,” he said casually, referring to the seemingly indestructible brand of cello case first used to store a sniper rifle and then as 007’s getaway toboggan in the 1987 spy flick The Living Daylights.

The sooner Isserlis has his boarding passes, the faster he and his cello can hang out in a lounge. And so it was, maybe in the early aughts, “perhaps even earlier, ages ago,” he said in an email, that he was in such a setting at Oslo Airport with his close friend, the violinist Joshua Bell, while waiting to board their return flight to London. Bell was on his laptop when Isserlis left him to cello-sit while he used a restroom.

The way Isserlis recounted the story, moments later a British Airways employee picked up his cello. When Bell objected, she replied, “This has to go on board now, or your friend doesn’t fly,” according to Isserlis’s 2007 Guardian essay. Bell jumped away from his laptop and ran after the cello. He eventually retrieved it after some verbal sparring with the airline employee, said Isserlis. Meanwhile, Isserlis reemerged to where he’d left Bell and his cello only to find the violinist’s open laptop. “My heart stopped,” he said in an email. “It was truly a horrible moment.” Bell confirmed the story through a spokesperson. When I asked Isserlis if Bell had left his valuable violin behind in the chase, Isserlis replied, “No, definitely not!!!” He can’t remember if the airline apologized for the Oslo incident, “but I think not.”

After some airport mishaps at the end of 2022, air travel was looking up for Isserlis at the beginning of 2023. “It was getting much better and then,” he paused, “the disaster at the Madrid airport.” “@British_Airways — you are a total disgrace,” he tweeted on Jan. 22. The airline had canceled his flight home from Madrid that day, booking him on a later flight. When he arrived at the airport for the new flight, he learned that flight too had been canceled. The airline then booked him on another flight the next day. But not his cello. “Scoundrels,” he tweeted.

Fourth Movement: FAQ Rondo

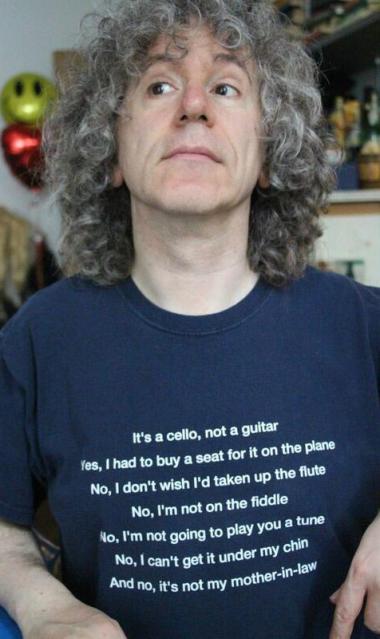

By his own admission, Isserlis’s patience and good manners can be tried, even by well-meaning fellow air travelers who, over the years, have posed the same inquiries to him. “All good questions,” he said. But it’s not fun to be asked repeatedly, he explained. So in 2013, he designed a T-shirt that displays down its front the answers to the seven most frequent things he’s asked in airports, including: “It’s a cello, not a guitar,” “No, I don’t wish I’d taken up the flute,” and “And no, it’s not my mother-in-law.” The same year he posted on Twitter a photo of him modeling the T-shirt with his chest puffed out. He still wears the T-shirt from time to time while traveling. “But people don’t always notice it,” he said in an email. “If they do, it can be useful — I just point to the answers to their inevitable questions.”

Isserlis’s frequent touring has allowed him to accumulate air miles from some airlines that provide certain perks, such as the special airport lounges he enjoys. Some of the airlines he flies on offer air miles for both his ticket and his cello’s. He isn’t sure which ones. “I think I get extra miles from British Airways, United possibly,” he told me. But collecting air miles for a ticketed musical instrument can be tricky to navigate for many musicians.

That’s what the late cellist Lynn Harrell discovered in 2012 when Delta Air Lines informed him in a letter that they had canceled his air-mileage account, removed any associated miles, and permanently banned him from rejoining their miles program, said Harrell’s blog post. Delta told Harrell that a separate account for “Cello Harrell” had never been set up 15 years earlier by a travel agent and that “sky mileage credit was not given for tickets purchased to carry excess baggage, such as musical instruments.”

Isserlis had something similar happen with one airline. Several years ago, he’d given an interview to a Condé Nast magazine he preferred not to name in which he mentioned his air-travel problems and praised Air Canada. That airline offers a 50 percent discount on a ticketed cabin seat for a musical instrument. A short time after the interview was published, Isserlis received a letter from the airline informing him tickets purchased for his cello seat could not collect air miles. “I said in the article, ‘The nicest airline is Air Canada.’ It was free publicity for them, and they take away the air miles,” he told me with a fleeting pout.

Creative Solutions for an Oversized Problem

Not many musical instruments are larger than a double bass. For four decades, Bang on a Can founding member Robert Black carted one on and off planes around the world. In the decades before airlines had a policy for musical instruments in the cabin, Black described an airport universe in which the mantra encountered at the counter, boarding gate, and on the airplane was “You can’t bring that in here,” he told me over video from his Hartford, Conn. home.

He used to travel with his French double bass, made by Charles Brugère in 1900. “It doesn’t really fit onto a cabin seat,” Black quipped. For a time, he often flew the now-defunct Trans World Airlines, which allowed musicians to buy two half-price seats for their instruments, giving him three seats in total for his bass and himself.

Over time, flying with his double bass became increasingly problematic as planes grew smaller and passengers became more hostile. “Sometimes downright abusive,” he told me.

About 15 years ago, he bought a sturdy David Gage travel case for his antique double bass to travel as luggage in a plane’s hold. But an incident while flying to London, perhaps during a custom’s inspection, Black speculated, left it damaged. “I can’t fly anymore with this instrument,” he decided. He purchased a travel bass — a deconstructed double bass called the B21 that fits into a suitcase and was made by the late French luthier Patrick Charton. Black checks it as part of his luggage allowance. “The travel bass kind of solved a lot of problems,” he told me, noting there is still occasionally a bump at check-in.

Unlike Isserlis, Black is not a frequent presence on Twitter. But he did take to Facebook when his travel bass was lost in transit when he was returning to New York from a music festival in Brazil. Black posted a photo of the gray suitcase on Facebook, asking for anyone flying back from the same festival who saw the case at any airport to let him know. “That post got reposted and reposted and reposted,” he told me, shaking his head, still marveling at the power of social media. Two weeks later, a bass player flying back from Europe saw the suitcase in the luggage area of the Toronto airport and notified Black. “That’s how I was able to get it back.”

The Charm of Russian Airport Customs

Russia is known for being an especially difficult place for musicians traveling with their instruments. Often, airport customs officials photograph and measure musical instruments every which way when they enter the country, according to Black, who recalled several occasions when his double bass was subjected to the surveying process. “They want to make sure the instrument you bring in is the one you bring out,” he told me.

Isserlis has often performed in Russia, where both his grandfather, the composer and pianist Julius Isserlis, and his father were born. His last visit was six years ago, on the day Brexit was announced, he recalled. When flying to Russia, he dutifully carries with him all the necessary paperwork, including proof of the cello’s provenance, ownership, and insurance. “In Russia you have to have all the documentation, the photographs, before you enter the country,” he told me. “If they don’t make a fuss when you enter, then they weren’t giving you what you needed,” likely leading to problems when trying to depart Russia. “It’s bad,” he said.

I asked Isserlis if he spoke Russian. “Plokho [badly],” he replied. When he played in Odessa, a small exhibition about his grandfather had been organized, and he was able to see his grandparents’ wedding certificate and related memorabilia. The war in Ukraine, however, has made him doubtful about returning to perform in Russia. “I don’t think I’ll play there again,” he told me. After a weighted pause he added, “I’ll have to see.”

Coda

A few days after meeting Isserlis in San Francisco, I heard him perform Camille Saint-Saëns’ two cello concertos with Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra at a church in Berkeley. In the lobby, I’d noticed his large, white Stevenson case open and looking lonely while, in the sanctuary, its traveling companion leaned in front of Isserlis as he drew his bow across its gut strings. The resonant tones he coaxed from the nearly 300-year-old caramel-hued instrument were a reminder of its unique beauty.

It’s a beauty appreciated by others in unexpected places. At Heathrow in late January, while still sulking at British Airlines after the Madrid airport disaster from a few days earlier, Isserlis tweeted that check-in that day had been painless. He’d had a new experience, however, at security. He’d had to open the cello case. “Not great, but okay,” he wrote. “As I left, the agent thanked me for giving him the chance to see such a beautiful object! Nice.”

Near the end of last year, Isserlis had also been at Heathrow, where he tweeted that check-in with British Airways had been “pretty blameless but Heathrow a nightmare.” There were vast lines to go through security. And then, just as he made it to the front of the line, the X-ray machine broke. For Isserlis, it was joy. He didn’t have to put the Stradivarius through the scanner. But at the boarding gate, he was asked the question that, he wrote, “evokes my hollowest laugh: ‘Have you traveled with a cello before?’ Haha.”