Update (Sept. 16): Today, Tinariwen announced that the band has had to cancel its upcoming North American tour, citing trouble with U.S. visa applications.

The itinerant camps that Tinariwen played in across Mali, Libya, and Algeria in the 1980s, when the group perfected a brand of music that would come to be called “desert blues,” were places of extreme conditions. Electricity was scant and unreliable, and the band’s members moved frequently between countries — swept up in the movement that prompted some Tuareg people to take up arms against Mali’s government as they fought for an independent state.

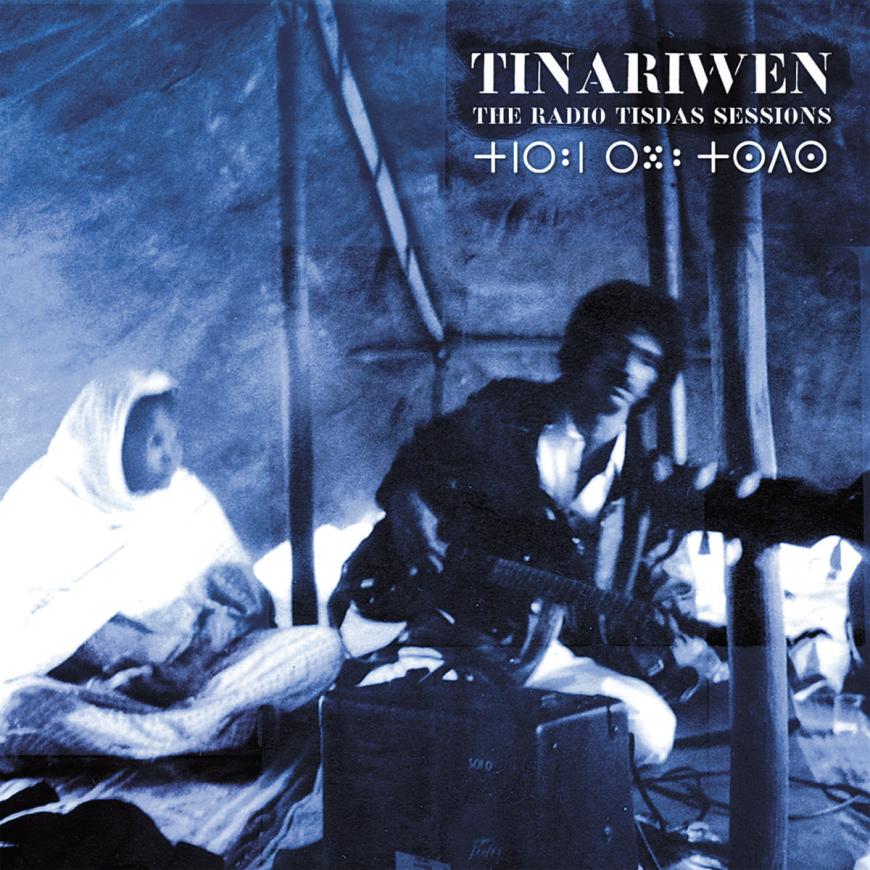

When Tinariwen performs next Monday (Sept. 19) at The UC Theatre in Berkeley and Tuesday (Sept. 20) at The Fonda Theatre in Los Angeles as part of its latest North American tour, the group’s history of itinerant movement and its people’s history of political upheaval will echo from every song, but so will something else that has helped Tinariwen become one of Africa’s most successful touring bands. That other thing is a history of musical influence, where blues and rock ’n’ roll — through cassette tapes that found their way to Saharan towns — helped inspire Tinariwen’s sound, which fans of those genres have recognized ever since Tinariwen released its first international album, 2001’s The Radio Tisdas Sessions.

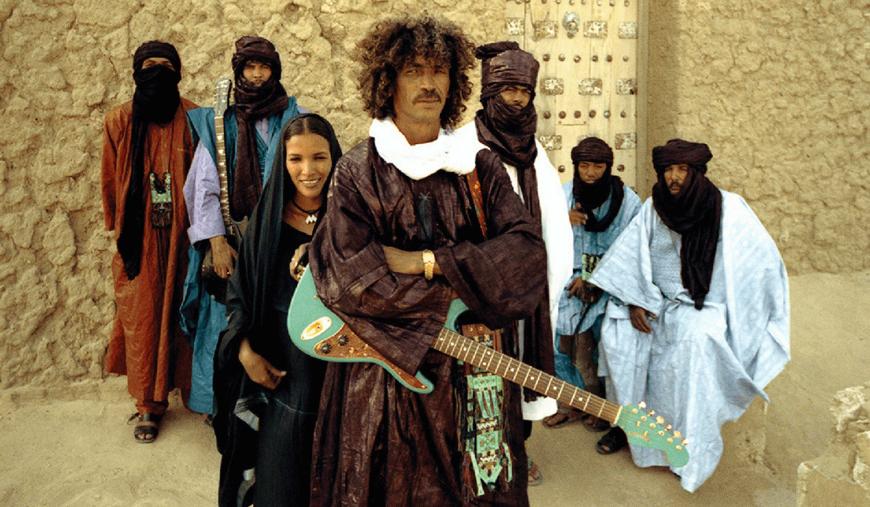

Tinariwen represents the globalization of music in all genres — whether classical, jazz, rock, or another tradition — where groups and musicians from non-Western countries have emerged with their own top billing, instead of staying “in the background,” where their job is to support a better-known artist without fanfare. Now that streaming services bring music instantly to people’s phones, and the general listener is much more aware of music from other countries, Western artists are increasingly collaborating with non-Western artists — which is why Tinariwen has recorded or performed with a growing list of high-profile names, whether it’s Carlos Santana, U2’s Bono, or Flea of the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Tinariwen’s 2011 album Tassili won the 2012 Grammy Award for Best World Music Album, five years before Yo-Yo Ma and the Silkroad Ensemble — a collection of musicians from Lebanon, Syria, Iran, Azerbaijan, and other countries — won the same Grammy for Sing Me Home. Tassili features Tinariwen’s collaboration with the popular U.S. group TV on the Radio, who accompanied Tinariwen for a 2011 appearance on Stephen Colbert’s The Colbert Report.

“Nomadic musicians from Mali” is how Colbert introduced the group, who spoke briefly to the comic host and then performed the song “Tenere Taqhim Tossam,” singing these words in the Tamashek language:

“The desert is mine

Ténéré, my homeland,

We come to you when the sun goes down

Leaving a trail of blood across the sky

Which the black night wipes out.

The desert is hot

And its water hard to find

Water is life and soul

To all my brothers I say

The desert needs to be unified!”

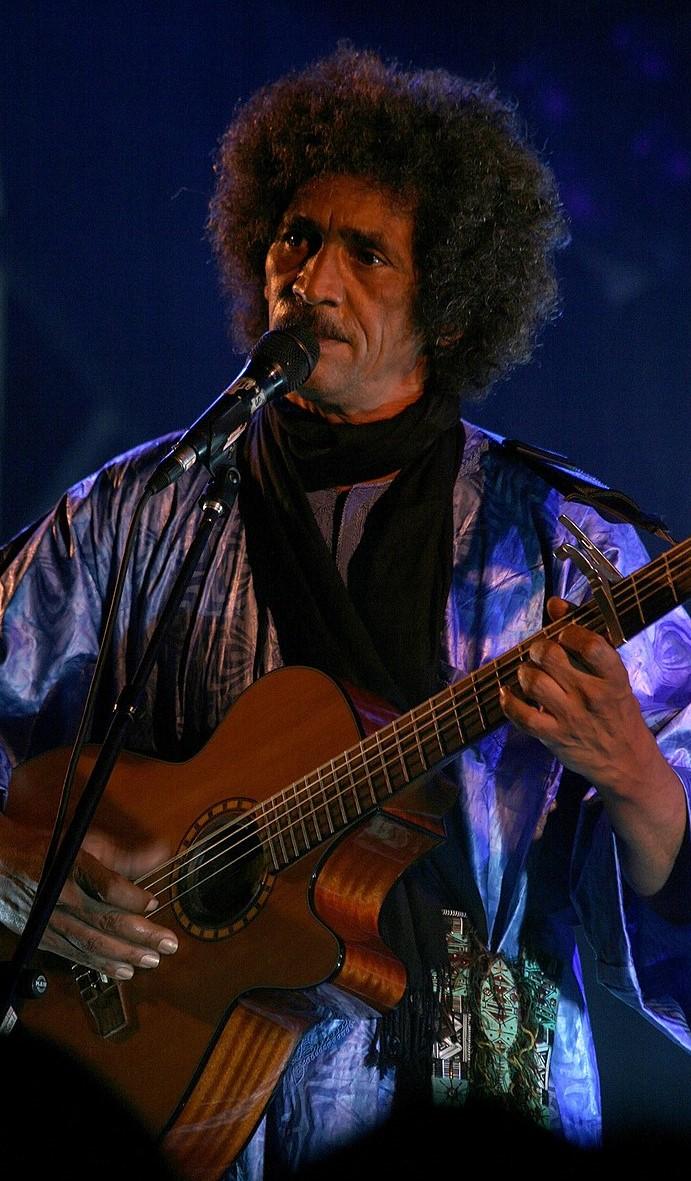

The term “desert blues” entered the musical lexicon when Tinariwen released The Radio Tisdas Sessions. But as Abdallah Ag al-Housseini, Tinariwen’s lead guitarist and one of its primary singers, told me in 2004, the group’s music really shouldn’t be categorized that way — just as “Tuareg” is also a misrepresentation, as the name derives from an Arabic term meaning “abandoned by God.” Ag al-Housseini prefers “Kel Tamashek,” which means “people who speak Tamashek.”

“Our music shouldn’t be called ‘desert blues,’” he said. “It’s a term coined by Americans. Tamashek people used the term to be recognized in the West, but we want to be known as Tamashek people. … [The music] is a way of reflecting the suffering and the pain of the Kel Tamashek people. … We’ve been working for years to be able to go [outside of West Africa] to express the message of our people.”

That message includes songs about love, romance, and other universal subjects. And Tinariwen, which has now released nine albums and received multiple Grammy nominations, opened a musical door to other “desert blues” musicians from Mali and neighboring countries, including Terakaft, Omara “Bombino” Moctar, and Mdou Moctar — all of whom have gotten serious attention in the U.S. and Europe, with Mdou Moctar garnering a big TV profile on PBS’s NewsHour Weekend. For fans of music from around the world, the attention that Tinariwen has brought to the Saharan region and people who speak Tamashek is reminiscent of the attention on India’s music after the Beatles met Ravi Shankar and George Harrison began incorporating sitar into songs like “Norwegian Wood.” That swell of interest brought Shankar, sarodist Ali Akbar Khan, and a continuing lineup of musicians to Western prominence.

In jazz, a generation of musicians who came of age in the 1950s and ’60s — including Pharoah Sanders and Randy Weston — visited Morocco and recorded with Gnawa musicians, bringing greater prominence to a musical art form descended from West African slaves in Morocco, though no Gnawa musicians have emerged as big names who tour the U.S. as headliners.

In classical music and opera, China has been a country of deep fascination for Western composers and musicians — and has been a musical influence on the West. Rutgers University scholar Nancy Yunhwa Rao says Chinese opera had an outsized impact on American culture in the 1920s and ’30s, while Inna Faliks, who heads the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music’s piano department, says the future of classical music lies in China, where Chinese audiences are more drawn to the music than Western audiences are. The global popularity of such Chinese pianists as Lang Lang and Li Yundi also testifies to China’s growing role as a country that, by itself, can produce musicians who stand alone on Western stages, without the help of a “bigger name.”

Tinariwen sings almost exclusively in Tamashek, but this too is a reflection of the world’s new musical realities: Translations on the internet are easier than ever to get, and every one of Tinariwen’s releases comes with lyrics already translated into English, which has become a global lingua franca. Even Tinariwen’s website emphasizes English. And so at every Tinariwen concert, longtime fans who don’t know formal Tamashek will sing along with at least some of the group’s lyrics, a phenomenon that I’ve witnessed at Tinariwen’s previous U.S. concerts.

Still, Kendra Salois, an ethnomusicologist and assistant professor at American University in Washington, D.C., who has done frequent research in North Africa, particularly on hip-hop but also other musics from the region, thinks that Tinariwen benefits from its fans’ de-emphasis of the band’s Tamashek language and their emphasis instead on the music’s arresting sounds. Being endorsed by popular Western audiences helps grow the fandom, says Salois, who stresses that her opinions about Tinariwen are based on “informed speculation” rather than academic study.

“For audiences who enjoy [global] music, the unintelligibility of the language is not very important,” Salois said in a phone interview. “And in some cases, not understanding the language might be a marker of something that’s interesting. Beyond that, Tinariwen creates beautiful music, and they’re masters on their instruments. Their vocal timbre is arresting. And the melodies that they construct are very similar to United States blues music. So it’s familiar and graspable to audiences that way.”

Salois also points to the long history of American musical interest in North Africa, which includes Weston living in Tangier for many years, and to the fact that Tinariwen embodies the way music from one region of the world will influence another region and then reverberate from there, even back to the original region in a different but recognized form.

“We can trace historically the interest in Morocco that brings musicians to learn specifically about Moroccan musics, and those musicians take what they’ve heard and reproduce it in ways that feed back into what we think of as Western popular music broadly speaking, and [we] see that recirculation continue over generations,” Salois said. “It works both ways. The Moroccan band Nass El Ghiwane was famous for adopting and adapting the core format choices of U.S. and British rock bands, and then taking traditional instruments and traditional melodies and traditional rhythms and creating songs that don’t sound like U.S. and U.K. rock at all but do need some of that rock-band format to sound the way that they do, and that was really new in the 1960s and ’70s. This circulating pattern of absorption has certainly happened in jazz. Often, it’s a sustained engagement.”

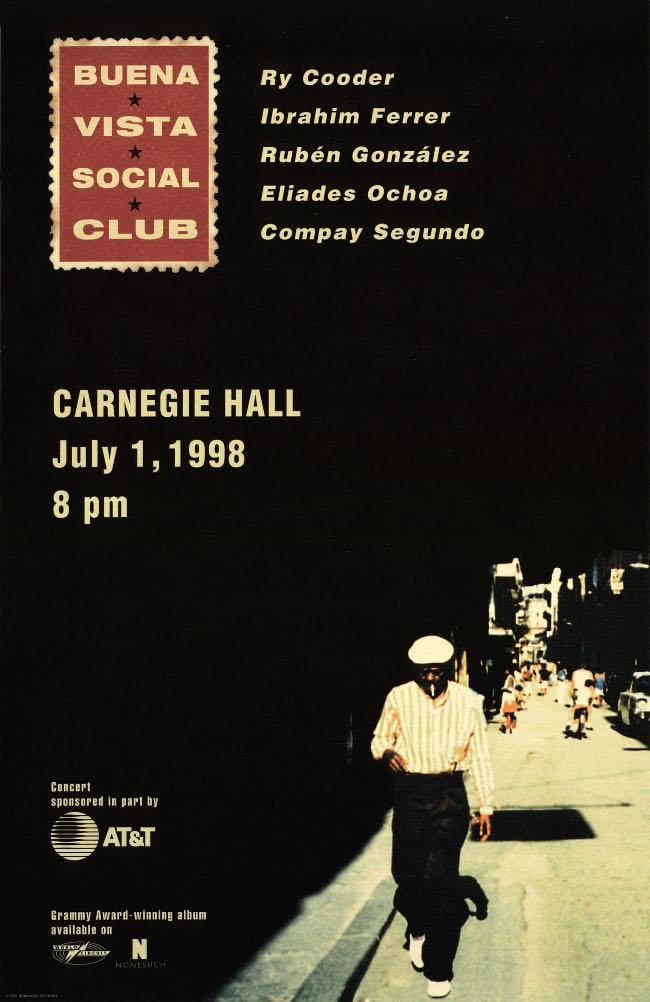

The best antecedent of Tinariwen’s popularity may be Cuba’s Buena Vista Social Club, a super group of older singers and musicians that emerged in the mid-1990s, ascended world music charts. and played venues like New York’s Carnegie Hall. Like Buena Vista Social Club, Tinariwen’s history of withstanding challenging conditions prepared the band for the highs and lows of constant touring.

On its 2019 U.S. tour, Tinariwen made headlines not for its music but for its show in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where a few extremists in the area condemned the band’s scheduled appearance and its wearing of traditional Kel Tamashek head coverings, which one extremist said made members look like “terrorists.” With the support of Winston-Salem’s mayor, who proclaimed Tinariwen’s date as “Tinariwen Day,” and also the support of North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper, who signed a letter that welcomed Tinariwen to the state and championed the group’s music, the band played in Winston-Salem without incident.

The group continues to release albums that explicitly stress the need for reconciliation and dialogue in Mali, where political tensions and threats of war are still high, and that implicitly stress the need for reconciliation and dialogue wherever tensions are high — even if that conversation is within one’s self and doesn’t lead to perfect results. The song “Mhadjar Yassouf Idjan,” on Tinariewen’s 2019 album Amadjar, which features American guitarist Warren Ellis, embodies this approach:

“How can I live with the emptiness

That has taken hold of my soul,

And has devoured me little by little?

The worse thing is that every time

I try to lighten my heart and forget,

Her image reappears, and I run headlong into the abyss.

When I express the burning wounds of my soul and my heart,

She doesn’t even notice.

It’s when the world goes to sleep

And silence alone settles in,

That I feel this painful longing.”

This song is a powerful invitation to persevere.

Looking back on Tinariwen’s 21 years of performing internationally, fans see the group’s music as ushering in a new era of global sound-making that shows no signs of abating. Tinariwen’s music is hypnotic and poetic, with guitar riffs that fly across pentatonic scales and voices of different tenors that veer from deeply plaintive to exuberant and ecstatic. American blues music can inhabit this same musical terrain. It’s no surprise that, in 2007, Tinariwen opened for the Rolling Stones. And it’s no surprise that American observers who heard Tinariwen for the first time called the group’s music “desert blues.” But as Tinariwen moves onward in its career, we’re hearing the music as universal, not comparing it to more familiar genres. Colbert, after witnessing the TV performance, repeated the word “thanks” as his live audience applauded rapturously.

The members of Tinariwen speak very little English, but they understood that word completely.