Houston Symphony did something extraordinary during the weekend: It gave a concert.

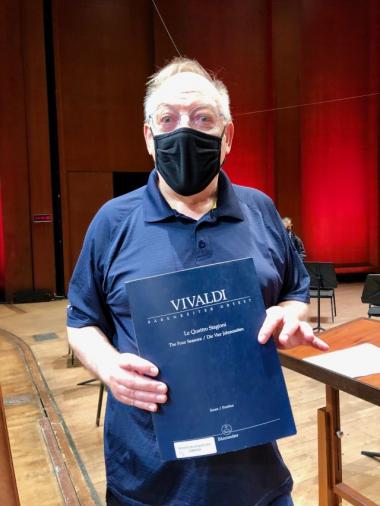

At the time of COVID-19’s cancellation/postponement of most symphony, opera and ballet performances in Europe and almost all of them in the U.S., Nicholas McGegan ventured forth from Berkeley to Houston to lead a distanced-and-masked concert on Saturday.

The event was among a few harbingers of what symphonic music is likely to be in the near future, if we are lucky, or even in the long run, if the virus keeps its deadly upper hand.

“I am having a terrific time,” McGegan said. “The Symphony staff have really made sure that every possible precaution has been taken. The only strange thing is that everybody on stage is sitting much further apart than usual so it is a little bit harder for everyone to play together, at least at the first rehearsal.

“However, everyone is getting accustomed to socially-distanced music making and there is such a mood of joy at being able to play again. This is my first concert since March 8th, so personally I am thrilled!”

COVID-19’s impact has made everybody miserable, but for McGegan, 70, who has been girding the globe, leading thousands of concerts and opera performances in his half-century-long career, four months’ inactivity was intolerable.

“After months without performing, this invitation [from Houston Symphony CEO John Mangum, formerly with SF Symphony] is manna from heaven. I have never conducted wearing a mask but if Zorro can swashbuckle around California on horseback, I should be able to wave my arms around in Texas!”

McGegan — music director laureate of the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra — led the live concert, streamed for a $10 charge, and attended by an audience of a dozen contributors in Jones Hall, which can seat 3,000.

The concert featured the late African American composer William Grant Still’s “Summerland,” from his Three Visions suite; Mozart’s Eine kleine Nachmusik; and Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons.

The Vivaldi is usually performed with a guest artist violinist, but McGegan and Mangum arranged for four orchestra members to be soloists — Boson Mo for “Spring,” Christopher Neal for “Summer,” Amy Semes for “Fall,” and MuChen Hsieh for “Winter.”

“It’s a bit like giving a concert in front of royalty not that I have much experience of that,” says McGegan, one of the world’s preeminent experts in baroque music, which often had only royal retinue as audience.

McGegan has also earned connection with royalty, having been made an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE) “for services to music overseas”; received the Halle Handel Prize; the Order of Merit of the State of Lower Saxony (Germany); the Medal of Honour of the City of Göttingen, and numerous other awards.

Mangum, 45, was born and raised in Danville and attended his first symphony concerts in Davies Hall as a teenager. As director of artistic planning first for the New York Philharmonic and later “coming home” to the SF Symphony in the same position, he worked here with Michael Tilson Thomas, planning programs and engaging artists. Mangum became president of the Philharmonic Society of Orange County in 2014, and CEO of the Houston Symphony last year.

After the concert, Mangum told SFCV: “Nic was our first guest conductor since March, when we were in the middle of rehearsing John Adams’s El Nino with David Robertson when the stay-at-home order came down. It felt like a critical next step in our path back to some kind of normalcy.”

The orchestra has not been at rest in recent weeks, providing weekly concerts of large chamber pieces and chamber-sized orchestra works with conductors from the Symphony, such as Steven Reineke, principal pops conductor, and conducting fellow Yue Bao.

“It was so great to have Nic with us this weekend,” Mangum said. “We have a world-class orchestra here — you could tell that, I think, from the level of playing our four violinists brought to the Vivaldi, and from the whole evening in general — and we have to do everything we can to continue bringing music to our community and now, to our growing audience around the country and around the world.

“Live musical performance is why we exist, and the way back to playing for audiences is challenging right now, but I do think there is a way. We’ll get there, and if we can help other orchestras with what we’re doing, so much the better.”

McGegan has had a three-decade-long relationship with the Houston orchestra, beginning with a 1989 Giulio Cesare at the David Gockley-run Houston Grand Opera (with the Symphony as orchestra, as it used to be in San Francisco too), and says knowing many of musicians so well there “really helped us all put this show together, certainly not a shotgun wedding.” Back in Berkeley on Sunday, McGegan spoke of his experience:

All credit for the program and the choice of Vivaldi soloists must go to John Mangum. He really is the Prince of Symphony Executives. I think that the Still work was a request from the harpist. What a lovely piece.

John planned this concert as part of a series. In most of the programs, there was a work by a Latin-American composer, an African-American one, and a woman. John’s knowledge of the repertoire is encyclopedic.

Two of the violin soloists have only joined the orchestra very recently: Bosun who played Spring and Amy who did Autumn. What a terrific way to encourage young talent within the group. In a normal show, performers draw a lot of energy from the audience, not just the applause, but this felt almost like a studio recording, even though we knew that we were playing to an unseen, on-line public. However, we were able to create our own energy on stage.

It was really odd conducting with a black mask covering half my face. I smile a lot on the podium, which was rather pointless when no-one can see the lower half of my face. It is hard to convey emotion when one is facially con sordino [muted]. I almost felt like painting a big grin on my mask! If I do a similar show with a mask, I must practice making my eyebrows more expressive!

Luckily, we had plenty of rehearsal so that we got used to performing socially distanced. The Mozart was fairly straightforward but the Vivaldi, even though it is very familiar to all the musicians, does have a lot of tempo changes and free sections that can be tricky to coordinate even when the players are bunched together. Kudos to the musicians for doing such a grand job."

In Houston, live concerts from Jones Hall continue during the summer, while the 2020–2021 season remains a prospective Prosperous Voyage awaiting a Calm Sea.

Gwen Watkins, of the Houston Symphony marketing department, reported happily after the event: ‘HWe sold 1,360 tickets which is our most to date for streamings. Age spread was similar to other Live from Jones Hall concerts, but skewed a little younger: 29 percent were ages 65+ instead of usual 33 percent, 10.2 percent were ages18–24 vs. usual 6 or 7 percent.”

Total views: 3,173, divided between 2,395 views on Saturday, and 848 views on Sunday; there were 938 concurrent viewers, the highest number of unique viewers watching live at one time.