Seiji Ozawa, a seminal international figure in classical music, died on Feb. 6 in Tokyo at age 88. Press reports said heart failure was the cause of death; Ozawa had been dealing with serious, potentially fatal, illnesses for years but remained active with several of his educational projects for young musicians, such as the Seiji Ozawa Music Academy.

Decades before many Asian classical music stars would become prominent in the West, Ozawa’s pathbreaking conducting career saw him leading the Chicago Symphony’s Ravinia Festival (1964–1968), the Toronto Symphony (1965–1969), the San Francisco Symphony (1970–1977), the Boston Symphony (1973–2002), and the Vienna State Opera (2002–2010) — among other orchestras.

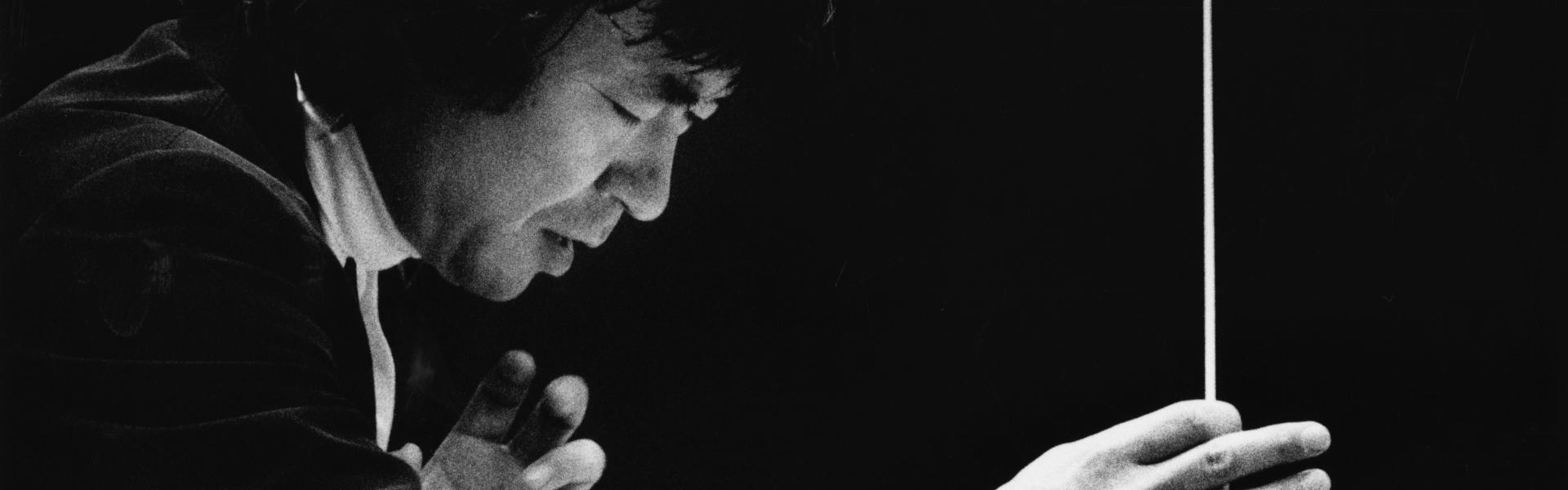

As critic Anne Midgette summed up in a 2015 Washington Post article, “For a couple of decades, Seiji Ozawa was one of the most familiar faces in American classical music. Turn on your TV, or look in your record store, and you’d see him: the mane of Beatles-like hair, the signature turtleneck in lieu of a starched shirt, the emotive energetic gestures.

“He ruled the Boston Symphony Orchestra, one of America’s most venerable and honored orchestras, for a record 29 years. He recorded just about everything.”

The Boston Symphony responded to the news of Ozawa’s death by commemorating how the orchestra under its longest-serving conductor “entered a global era, through a renewed commitment to commissions and contemporary music, a prolific number of recordings, radio and television appearances, and history-making tours.”

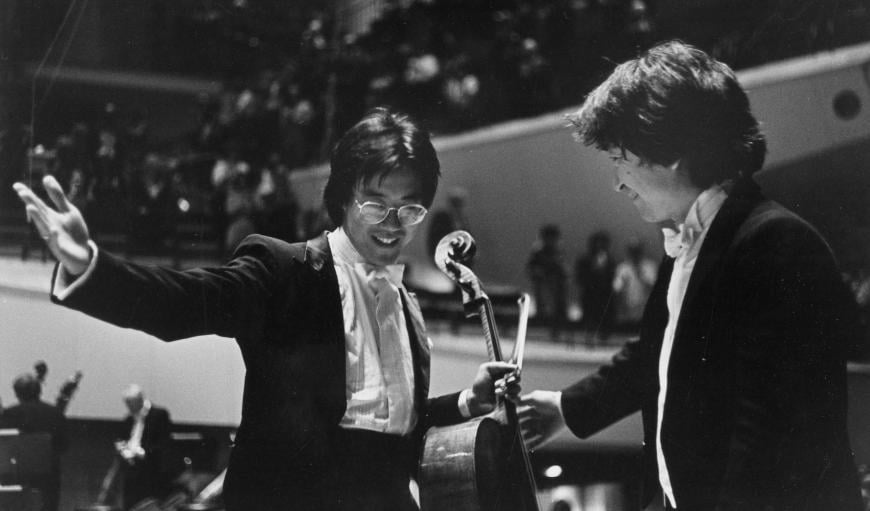

Cellist Yo-Yo Ma echoed the Boston announcement by saying that Ozawa “paved the way in many ways for Asian musicians, being one of the first ones to arrive on the scene and do what he has done.”

Ozawa conducted the SF Symphony in the War Memorial Opera House, which was the orchestra’s home before moving to the newly built Davies Symphony Hall in 1980. On a visit to the city in the 1970s, I first saw the orchestra perform and wondered about the bright red soles of Ozawa’s shoes, finding out later that they were just reflecting the color of the podium.

Throughout his long career, Ozawa didn’t bother with the “uniform” for conductors, instead sporting an unorthodox wardrobe that consisted of a white turtleneck and at times colorful coats.

His years as music director in San Francisco were meaningful for the orchestra and even the city, which benefitted from the national and international attention the conductor created. He led the SF Symphony in its first commercial recordings in over a decade and took the orchestra on a tour to Europe and the recently opened-up Soviet Union.

“We mourn the loss of our former music director and friend Seiji Ozawa,” wrote the SF Symphony musicians on their Facebook page. “Seiji’s leadership propelled our orchestra to new heights and laid the groundwork for the truly transformative years to come after he left. Many current and recently retired members of the orchestra have fond memories of their time spent with him.”

SFS assistant concertmaster Jeremy Constant added that Ozawa “brought international stature to the entire area.” The SF Symphony Chorus was established in 1973 at the conductor’s request.

Bay Area native Elizabeth Baker writes: “Seiji was music director in 1972 when my mother, Virginia Baker, was hired for the position of second assistant concertmaster. It turns out she was one of the first women hired by a major orchestra for a titled position. Thank you, Seiji, for considering her qualifications over her gender.”

Ozawa’s progressive attitudes also led to a position-ending conflict with the SFS board and some of the orchestra’s musicians. The players’ committee denied tenure to timpanist Elayne Jones and bassoonist Ryohei Nakagawa, two young non-white musicians Ozawa had selected.

After he left his position here, switching full-time to Boston, Ozawa returned to San Francisco as a guest conductor — and to play singles tennis for hours in Golden Gate Park, defying court policy by going shirtless.

The SF Symphony has yet to release an official statement on Ozawa’s death.

Ozawa was born on Sept. 1, 1935, to Japanese parents in the Japanese-occupied Manchurian city of Mukden, now Shenyang in China. He began piano lessons at age 7, and when his family returned to Japan in 1944, he began studying the instrument seriously.

In 1950, Ozawa broke two fingers in a rugby game, ending his piano studies, and his focus shifted to conducting and composition. With unusual speed, he achieved prizes in both areas at the Toho Gakuen School of Music and started to work with the NHK Symphony Orchestra and the Japan Philharmonic while still a student. He would graduate in 1957.

At a young age, Ozawa won first prize at the International Competition of Orchestra Conductors in Besançon, France. His success there led to an invitation by Charles Munch, then the music director of the Boston Symphony, to attend the Berkshire Music Center (now the Tanglewood Music Center), where Ozawa studied with Munch and Pierre Monteux.

There, Ozawa won the Koussevitzky Prize for outstanding student conductor, Tanglewood’s highest honor, and a scholarship to study conducting with Herbert von Karajan in (West) Berlin. Leonard Bernstein became aware of Ozawa, helped to train him, and appointed him assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic.

Ozawa served with the NY Phil for the 1961–1962 and 1964–1965 seasons, and he made his first appearance with the SF Symphony in 1962.

Ozawa is survived by his wife Vera and children Seira and Yukiyoshi.