Greed, lust, betrayal, hubris: These tragic themes are perfectly at home in an operatic or orchestral setting. When the dramatic lyrics in question were penned on Staten Island, the scene becomes much less common, and when two rappers take the stage backed by a chamber group, precedent goes out the window altogether.

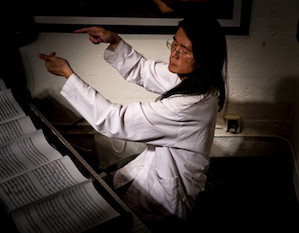

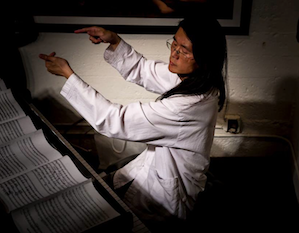

Ensemble Mik Nawooj, led by pianist and composer JooWan Kim, is indeed a unique phenomenon. Kim has augmented his new-music ensemble with the MCs and a rhythm section composed of double bass and drum kit. The music merges concert and hip-hop aesthetics, resulting in a driving juxtaposition of bombastic tension and melodic release. It is an unapologetic and surprisingly coherent sound.

“This is my answer to dodecaphony, serialism, minimalism, post-minimalism, and concert music in general,” says the Korean-born Kim, who emigrated to the U.S. to study at Boston’s Berklee College of Music, which he followed with a master’s in composition from the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. It was while at the Conservatory that Kim first began experimenting with a classical/hip-hop hybrid, presenting the first live piece “as a joke” in 2005. He began to consider doing it seriously when the performance received some unexpected attention from local press and musicians.

This attention persists. Ensemble Mik Nawooj appears at Yerba Buena Gardens Festival in downtown San Francisco on Saturday, May 31, performing pieces commissioned by the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts for its 21st anniversary in November. That event will feature music from 1993 (a seminal year for hip-hop), and this weekend Kim presents four arrangements from that program: C.R.E.A.M. (an acronym standing for “Cash Rules Everything Around Me”); Shame on a Nigga; Ain’t Nothing to Fuck With, by New York’s Staten Island–based Wu-Tang Clan; and Gin and Juice, by California’s own Snoop Dogg.

Kim rejects the title “classical composer” entirely and calls himself a composer with classical training who writes not “art” but ambitious “pop” music.

What began as a joke has become a serious endeavor. For Kim, this programming reflects a political position that music should not be a “cult experience,” aimed at a restricted audience that can understand the complicated language of modern concert music, but should instead connect with the general population (his wording reveals a clear delight in ruffling feathers).

In school, Kim drew major inspiration from Louis Andriessen, and the Dutch composer’s rejection of orchestral instrumentation and embrace of diverse musical influences provide a clear genealogy for Ensemble Mik Nawooj (which is the composer’s name backward, by the way).

Kim was particularly compelled by Andriessen’s Marxist embrace of art music for the working class and hopes to take the impulse one step further — rejecting the title “classical composer” entirely and calling himself a composer with classical training who writes not “art” but ambitious “pop” music.

The cultural commentary of hip-hop played a large role in this decision. “Once I realized the social context and the kind of things that they were saying, it blew me away. I could understand the necessity in the music — it’s a very sincere and powerful expression,” he says. “If you listen to concert music, it doesn’t have the same urgency.”

Kim, who has grown to condemn academic music altogether (“I am violently against it”), finds that the broad reach of popular music in no way diminishes its artistic achievement. That’s an attitude that he shares with many, if not most, composers of his generation. But for Kim, it’s also linked to sociopolitical ideas.

What marks his work as unique is the marriage of classical techniques to this omnivorous disregard for cultural authority — a definitively hip-hop attitude.

“When I came here, I realized it was very different in the sense that pop music was deeply associated with subcultures,” explains Kim. “Koreans don’t have that. Europeans don’t even have that, either, in terms of pop music. I thought that was weird, so I continued to listen to whatever I wanted to.” Indeed, what marks his work as unique is the marriage of classical techniques to this omnivorous disregard for cultural authority — a definitively hip-hop attitude.

Ensemble Mik Nawooj is fresh off a performance of Malcolm X: A Hip-Hop Oratorio, a piece Kim developed from what was originally a short experiment years ago. He was inspired by Malcolm X’s personal transformations, which Kim thinks provide an analogy for the evolution of hip-hop. He chose the oratorio format not for its tradition of religious themes (though that could have been appropriate in this instance, as well), but because the dramatic narrative in a concert setting appealed to him. He selects the aspects of discipline that fit his preferences and forges his own path forward.

This is hip-hop: a culture of sampling, of taking particular elements out of context and mixing them up in new and original ways. It’s a particular usage of a universal trait of human culture. In this sense, despite the strings and woodwinds, and despite the musical indebtedness to Debussy and Beethoven, Ensemble Mik Nawooj is indeed a pop act.

Various excerpts of this story were originally published in the April 8 issue of the San Francisco Bay Guardian.