Who’d have thought that the opening two minutes of Richard Strauss’s tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra, composed in 1896, would become one of the most recognizable and iconic bits in musical — and cinematic — history? Cue the beginning of Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey, with the MGM logo and credits accompanied by low orchestral stirrings that yield to unison trumpets in fanfare mode, and voila, a magnificent earworm.

Thus did the Los Angeles Philharmonic begin a thrilling performance at the Hollywood Bowl last Thursday as the Kubrick film was screened under the stars. Even the airplanes and choppers — and there were many that night — seemed a piece of this film that continues to both confound and hold viewers in thrall with its Oscar-winning effects, technological realism, and eerie prescience.

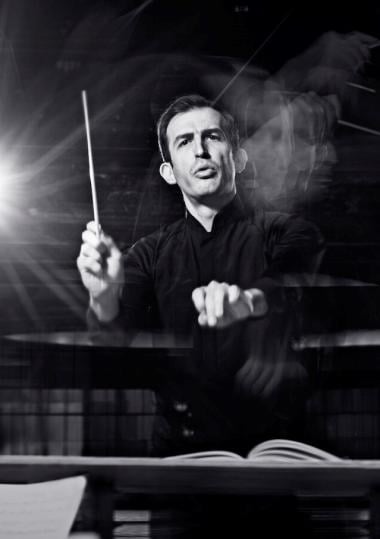

Under Berlin-based conductor Caleb Young, the orchestra and the Los Angeles Master Chorale (prepared by Associate Artistic Director Jenny Wong) proved up to the task of traversing this nearly three-hour endeavor, which included an intermission. Long recognized as one of the greatest science-fiction films of all time, Space Odyssey was also screened at the Bowl with live orchestral accompaniment in 2015 and has been performed that way in more than 25 countries around the world.

This might not have been the case, however, had Kubrick stuck with any of the four composers he had initially chosen to write an original score, including Alex North, who had worked with the director on Spartacus but was ousted during Space Odyssey’s postproduction, with Kubrick opting to make use of classical music instead. Indeed, the score, like the film — whose screenplay was written by Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke — broke with many of the norms of its time.

After the indelible opening credits, the movie begins some 4 million years ago in Africa, with a bevy of scruffy primates living their best lives until a spooky black monolith appears. The music here is the Kyrie from György Ligeti’s Requiem, and Young led members of the Master Chorale in a spectacular rendering, their voices unearthly, sustained, and reaching a fever pitch that seemed to reverberate throughout the Cahuenga Pass. Then a little-known Hungarian avant-garde composer, Ligeti used here what he called “micropolyphony,” a textural approach to canons and rhythms resulting in tone clusters. And as a result of Kubrick’s film, Ligeti shot to fame.

But back to the apes. Inspired, or puzzled, by the monolith, one of them picks up a bone, uses it to kill another of his group, and ultimately throws it into the sky, which, in what has been described as the most elongated fast-forward in film history, morphs into a placidly floating satellite.

Set to the strains of another Strauss composition — Johann Jr.’s Blue Danube waltz — this scene is a kind of balletic transition to the future, the lilting melody ideal for a fashionably clad flight attendant wearing antigravity boots and treading in time to retrieve a floating pen or serve a meal.

And while there are only 40 minutes of dialogue in the film, the plot and particulars of 2001: A Space Odyssey are a source of continual debate. We not only get a view of human evolution, a landscape of the moon (featuring music from Ligeti’s Lux Aeterna), and a mission to Jupiter (set to the poignant Adagio from Aram Khachaturian’s ballet Gayane), but we also experience the journey of astronaut Dave Bowman (a studly Keir Dullea).

After tangling with HAL, an egomaniacal artificial intelligence, the green-eyed protagonist embodies the space-time continuum as viewers are treated to more Ligeti. Here is the return of the Requiem, as well as the dense sounds of the complete eight-minute Atmosphères and an electronic alteration of Aventures, heard in the penultimate scene.

As the film comes to its remarkable conclusion, Bowman, now aged and dining in silence in a pristine, neoclassical room, sees himself lying in bed and beholding, yes, a monolith before he dies and is reborn as a glowing Star Child. The rebirth, set once again to the two minutes of Zarathustra, had the LA Phil playing as boldly and as beautifully as if the ensemble were just getting started.

Kubrick’s vision was a prophetic one, although we haven’t yet discovered alien life. Space Odyssey was released only a year before a man walked on the moon. One can imagine Steve Jobs conjuring smart phones, and with them FaceTime, while watching the scene where astronaut Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) calls his daughter on her birthday via a Ma Bell videophone.

And can we talk about HAL, the AI at the heart of the film? With the emergence of sophisticated artificial intelligence programs capable of performing an ever-growing number of human tasks, there is also the existential threat that this technology will replace actors — deepfakes are already becoming more prevalent — as well as be used to write college essays or, perhaps, a review such as this.

While the year 2001 has come and gone, the film 2001 has a legion of fans. This was evident at the Bowl, where the audience sat rapt throughout and then, filing out of the bucolic venue while the Phil played the Strauss waltz over the end credits, seemed to be, well, walking on air.

Correction: As originally published, this article misstated that Grant Gershon prepared the Los Angeles Master Chorale for this performance. In fact, it was Associate Artistic Director Jenny Wong who prepared the chorus.