This year's American Bach Soloists Festival and Academy focuses on the French contemporaries of Johann Sebastian Bach, and accordingly opened on Friday, August 7, with a program of varied orchestral suites by Jean-Féry Rebel, Jacques Aubert le Vieux, and Jean-Philippe Rameau.

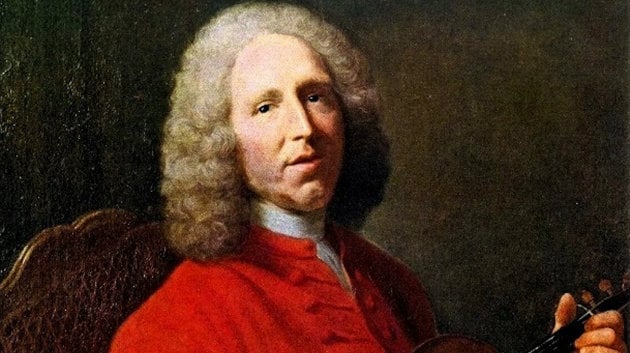

You’d be forgiven if you didn’t recognize some of these composers. Of them, Rameau is surely the best known to the musical public, while Rebel and Aubert are rarely performed. If you know Rameau, it's likely because of the advocacy and recordings of William Christie, with Les Arts Florissants, and that of Mark Morris, whose Platée has been performed many times. Rameau's Ouverture & Suite from Naïs, Opéra pour la Paix, took up the entire second half of the program, and though twice the length of each of the other suites, proved rather more engaging and interesting.

Not that there wasn't some inventiveness in the works of Rebel and Aubert. Rebel's Les Élements, Symphonie Nouvelle, especially, went out of its way to create novel harmonies and pictorial motifs. The suite opens with a movement called “Le Cahos” (Chaos), which strives to recreate the chaos of creation itself. You'd expect to find its tremendously dissonant opening chord in Bartók or Carter, not in the work of a French Baroque composer. As the 10-movement suite proceeds through the elements earth, water, and fire, Rebel charmingly illustrates the heaviness of the earth through a thumping motif in the lower strings. Similarly, water flows, and fire is represented by a stinging motif in the violins. Trumpets, horns, and timpani added color and weight to Rebel's orchestral sound, which became especially obvious in Aubert's Suite II in D Major, written for strings and winds only. The result was rather airy and lightweight.

Trumpets, horns, and timpani added color and weight to Rebel's orchestral sound, which became especially obvious in Aubert's Suite II in D Major, written for strings and winds only. The result was rather airy and lightweight. Again, the suite had charm to spare, as it progressed through a series of dance movements: a pair of rondeaux, a sarabande, pairs of rigaudons (a duple-meter dance), menuets, and gavottes, plus a fanfare, a pair of tambourins, and a closing chaconne. But charm can go only so far, and as well-conducted and played as they were, the Rebel and Aubert suites came across as music to be played in the background of court functions rather than music listeners might give their full attention to.

The Rameau Ouverture & Suite proved to be another matter entirely, more serious and altogether more interesting. The return of the trumpets and drums was a relief after the somewhat monotonously scored Aubert. Each of Rameau's movements was longer and more complex, with more interior contrast than those of Aubert and Rebel. Nothing in the preceding suites could really match the lyrical longing of Rameau's Musette, for example.

You could wish that the suite had been expanded to include a few of the vocal numbers from the opera, which might have deepened our understanding of how the dances fit into the whole. And this could have given some context to the number called the “Entrée majestueuse de Dieux” (Majestic entry of the Gods), which proved to be a sprightly, double-dotted delight — nothing like that more famous entry of the Gods.

The orchestra played with great enthusiasm and consummate skill, with Thomas providing lively leadership. And yet, because of the prevalence of dance numbers, the program felt like too much of the same thing. Still, we're lucky to have gotten a taste of Rebel and Aubert. There's great value in providing context for great composers by performing the works of their lesser contemporaries.

The ABS Festival continues with a number of concerts this week, and will include two performances of a rarity that's sure to be of great interest, the opera Semele – by Marin Marais, not the famous version by Handel.