It was a good day for Susanna Mälkki and the Los Angeles Philharmonic Sunday afternoon Nov. 7. A really good day.

The programming was adventurous and stimulating — a local premiere for a newish piece by Steve Reich, a modernist tour-de-force for a virtuoso violinist by John Adams, and modernist Rachmaninoff (all things being relative) — with a dance element loosely threading the three pieces together. The orchestra’s playing was on fire — sleek, together, with an enormous vitality going even beyond its usual high standards. And the music was being recorded, which might have contributed to the motivation to push the envelope harder.

The Reich piece, written in 2016 for London’s Royal Ballet, is called Runner — and it’s easy to see from the get-go how that name came about, for the opening bars scamper along at a quick pace before the violins overshadow the pulsating twin pianos. Fortuitously, Runner was being played on the day the delayed L.A. Marathon was launched not far from Walt Disney Concert Hall — a coincidence, no?

There are five continuous movements that shift from fast to slow and back to fast, so it feels like a typical three-part Reich construction of his later years, with the divisions between them blurred. Despite all of the activity from the pairs of mallet instruments, flutes, oboes, clarinets, and pianos, plus a small contingent of strings, the overall impression is languid and reflective.

This and another work composed just the year before, Pulse, suggest that this onetime radical, one of the chief apostles of minimalism, had entered a period of contemplation when he turned 80 (he’s now 85). Runner hasn’t had a commercial recording thus far (though I’ve heard a faster-paced promotional live recording from the publisher), so this concert might yield its first one.

Adams’s first Violin Concerto (the second would be Scheherazade.2) has been performed by many violinists since its premiere in 1994. But for Leila Josefowicz, taking it up was a turning point in her career, lifting her from being just another purveyor of the standard repertoire into the role of a supremely gifted, fearless champion of new music.

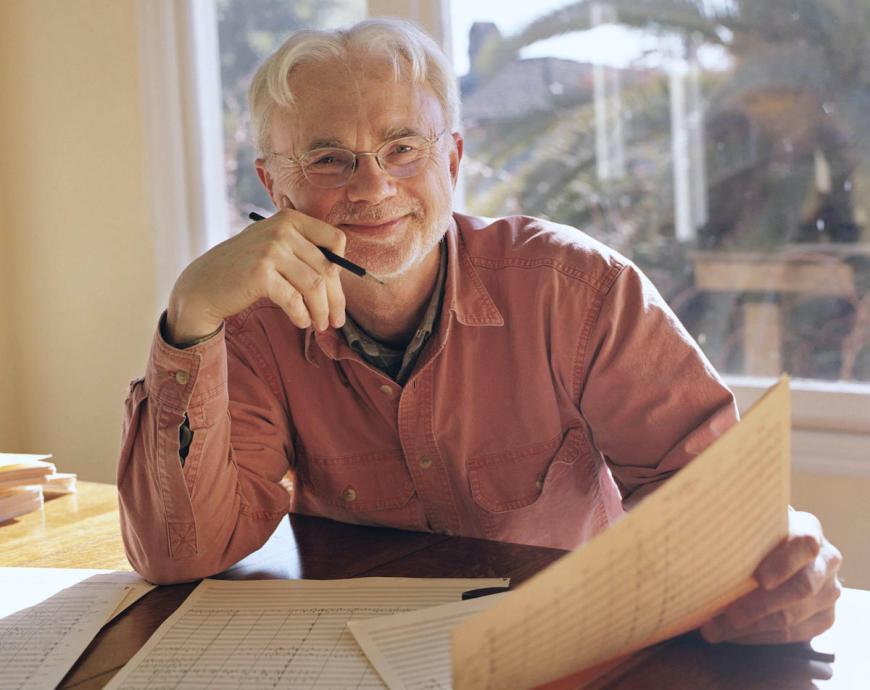

She still delivers the piece passionately, even fiercely, giving the first movement a slightly acidic edge as she toyed with the endlessly twisting main line. Even though the movement is written out, it sounded to me like a jam session in the best sense as the polytonal LA Phil strings and winds suavely rose above the steady pulse from the two walking basses. Later on, Josefowicz and Mälkki probed the hushed, mysterious elements in the second movement, and in the finale, the strings really turned up the gas, playing with high-energy fervor for Mälkki as Josefowicz cranked it up even more. The composer, who also happens to be the LA Phil’s Creative Chair, was present to share the bows.

Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances from 1940, his last work, took a long time to catch on: audiences missed the lush Romantic tunes from the second and third piano concertos that they doted on. Nowadays, though, recordings of the piece are plentiful in either the orchestral or two-piano editions, whereas you could count them on one hand 50 years ago.

When I call the piece “modernist,” I’m referring to the work’s quirky rhythmic elements, particularly in the third dance, the use of a solo saxophone, and the lack of sentimentality that brings the work decisively into the 20th century. Mälkki’s performance — the best I’ve ever heard of this work live or otherwise — emphasized that modernity, getting it on with a brisk, crisp tempo for the opening march tune, the most memorable one in the score. Everything was lucid and clear in texture yet packed with power, gathering urgency and pizzazz when the tune returned. She followed up with a graceful, freely phrased statement of the waltz movement that had a natural swing to the rhythms, and the details of the final dance’s scoring shone through the texture, driving toward an explosive coda.

Indeed, Mälkki seems to be getting better and better results each time she takes the podium here. I hope the Phil can keep her here in some capacity. But since the New York Philharmonic is looking for its next music director in the wake of the departing Jaap van Zweden, watch what happens when she makes her Carnegie Hall debut in front of the orchestra in January 2022.