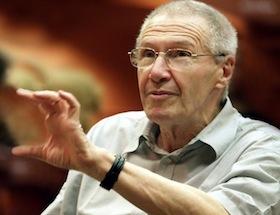

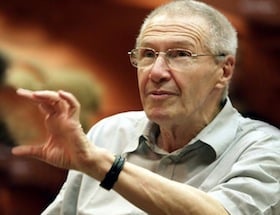

The contrast is startling between Pierre-Laurent Aimard the titan of piano and Aimard the man: ordinary, without pianistic mannerisms. Ah, but when he sits down to play — what a wondrous experience! His Tuesday evening recital at Herbst Theatre provided a dazzling diversity within the framework of unvaried excellence.

Ruth Felt's San Francisco Performances scored a coup presenting Aimard in his local recital debut. His appearances around the world are at the most prestigious venues: solo recitals in Berlin, London, New York, Paris, and Tokyo; concerto appearances with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment with Simon Rattle, and with the Cleveland and Chicago Symphony orchestras.

At 57, he has a half-century record of playing the most difficult contemporary music. If the math seems wrong, yes, it is true: Aimard was playing Schoenberg's music at age 7. He was still a teenager when he became Olivier Messiaen's favorite, and Pierre Boulez made him a soloist in his Ensemble Intercontemporain. Not just a child prodigy, but one in the difficult and thankless area of contemporary music.

Aimard is a virtuoso, but that's not out front, the audience gets nothing ostentatious, no tossing of hair, no enraptured gaze towards high heavens, nothing twitching. He plays the piano, plays the music. Not only that, but also something rare and special: He plays the silence between notes superbly.

The opening of the recital — with selections from György Kurtág's Játekok (Games) — was instantly stunning. This is austere, powerful, unusual music, outdoing Bartók himself, although the format is very much in the manner of Mikrokosmos. Of the minute-long pieces with few notes, "Fanfares" and, especially, "A Quiet Farewell to Endre Székely" seem to hang in the air, resonating long after the sound is gone.

It was especially here, and later with Kurtág's Szálkák (Splinters), that Aimard's uncanny ability to make silence a vital part of the music came to the fore. Individual notes lingered and gained special meaning from the pause before the next note is heard.

Pauses came into play again, but in another context: There weren't any. Marino Formenti and others have long "mixed it up" by performing various pieces, even from different composers, continuously, as if reading chapters in a book, rather than closing and opening the covers of several books. It's a tricky thing, which must be done very well to succeed.

Aimard upped the ante by concatenating works that have little — or nothing — to do with each other. He sandwiched between the two Kurtág sets, 11 of Schumann's Bunte Blätter, Op. 99 (Many-colored leaves), originally called Spreu (Chaff). As these short pieces are so different from Kurtág's, they are much varied in themselves, coming from various periods and moods. Aimard managed the self-imposed task of pulling together all this both seamlessly and meaningfully.

But then, still in the first part of the concert, Aimard exhibited something skirting bravado by concluding the Kurtág-Schumann mix with two Liszt pieces, one little known — with the bizarre trilingual title Unstern! Sinistre, disastro (Ill-fated, sinister, disastrous) — and the other one of the composer's most famous, Les jeux d'eau à la Villa d'Este (Play of the waters at Villa d'Este) — leading well into the Debussy set after intermission.

Unstern! has a curious kinship with Kurtág's music, even though separated by almost a century, and two very different kinds of Hungarian idiom, Kurtág's being authentic.

The similarity is in the craggy sound, and what program annotator Eric Bromerger identifies as "striking music, full of unsettled harmonies, rhythmic tension between the two hands, and driving energy that finally leads to a mysterious — and unexpected — close."

Debussy did his own "nonstop structure" in Préludes, Book II, and Aimard made these "many-colored leaves" his own, playing the dazzling variety of the 12 preludes with appropriate differentiation but consistent brilliance — although, typically and in a way difficult to explain, he made it all sound subtle. The music was in full bloom — especially "Bruyères," "Ondine," and "Canope" — and yet half-hiding a depth inviting the listener to explore... if only the very next bar didn't distract.

It's usually a task for the performer to let go of notes; listening to Aimard, it became the challenge to the audience.