The dean of Danish composers, Per Nørgård, celebrated his 90th birthday in July — and if this name is new to you, the American concertgoer, blame the unofficial edict that Scandinavian countries are allowed just one internationally famous composer each (in Denmark’s case, Carl Nielsen). I cannot recall ever encountering a note of Nørgård’s music in decades of concertgoing, so of course, we must turn to recordings to get an idea of how this prolific composer (over 400 works) has evolved a symphonic language of his own over 70 years of activity.

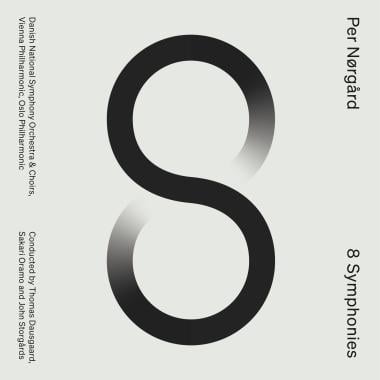

Nørgård’s eight symphonies have just been gathered into a four-disc boxed set by the Danish Da Capo label. Although these recordings with three different conductors and orchestras were released separately from 2009 to 2016, this is the first time that all of Nørgård’s symphonies have been packaged in one box.

Thomas Dausgaard and the Danish National Symphony Orchestra started the project with the Symphonies Nos. 3 and 7. About five years later, the cycle resumed with the Symphonies Nos. 1 and 8 played by the Vienna Philharmonic as led by Sakari Oramo, and John Storgårds and the Oslo Philharmonic finished it off with the Symphonies Nos. 2, 4, 5, and 6. Each disc is programmed as originally issued, so you’ll have to skip around from CD to CD to sample the cycle in the order in which it should be heard, for there is an illuminating, at times mind-bending, progression at work.

Nørgård shares with his late contemporary colleague, Finland’s Einojuhani Rautavaara, the ability to write in all genres in an ever-evolving series of styles — and both happen to have eight symphonies in their catalogues. Nørgård’s cycle starts with an impressive First Symphony (“Sinfonia austera,” 1953–1955) that is said to reflect his early Sibelius influence, but there are only a few distantly fleeting wisps of the latter’s First Symphony at most. Instead, the music’s troubled, anxious manner is more reminiscent of the first movement of William Walton’s First Symphony, which Nørgård may or may not have known — and the symphony hangs onto tonality for dear life as the anxiety tightens.

In the Symphony No. 2 (1970–1971), Nørgård’s personality begins to bloom. He had just invented what he called the “infinity series,” a form of serial composing based on intervals and less forbidding to the ear than Schoenberg’s 12-tone system. This one-movement symphony begins with a single sustained tone that splits into pitches hugging close to, and colliding with, each other, sometimes in quarter tones. The whole thing is quite beautiful, drifting along while maintaining a steady pulse.

The Symphony No. 3 (1972–1975) is the great one, swapping the steady flow of the Symphony No. 2 for a series of explosions of color. Eventually it settles into a new, fantastical, pleasurable, sometimes colliding wonderworld of sound, with voices gradually creeping into the mixture and taking over the second movement, which luxuriates for nearly 26 minutes. It even includes a brief outbreak of Afro-Cuban dance rhythms (how did he manage to slip that in?) before everything vaporizes as if in a dream.

From this point onward, Nørgård’s ideas become more rigorous and somewhat more succinct. The short Symphony No. 4 (1981) is in another sound world, one of understated, underlying anxiety in the opening movement that bursts out in thumping drums, dissonant strings, and brass blasts in the second (and last) movement, where for the first and only time in the cycle, you can hear a quote from Nørgård’s countryman Nielsen — a motif from the latter’s own Symphony No. 4.

Nørgård’s journey takes some weird turns in the Symphony No. 5 (1987–1990), with strange new noises lurking around each bend in the road: long pauses, gliding pitches, microtones, glittering percussion, a slide whistle, and even a quote from “Jingle Bells.” Esa-Pekka Salonen, the dedicatee, conducted the premiere in 1990, and the combination of avant-garde abstraction, color, and kookiness would have been right up his alley then. Like its three predecessors, this one fizzles out at the close.

After experimenting with various sequences of movements, Nørgård settles upon a three-movement form and similar timespans for each of the later symphonies. While tonality is entirely gone in the Symphony No. 6 (“At the End of the Day,” 1999), there is still much beauty in the sound, the colors coming mainly from the piano, winds, harp, and mallet percussion, the argument building in tension until a jaunty syncopated theme announces the finale. The weightier Symphony No. 7 (2004–2006) is frankly a puzzle — one amorphous, disconnected episode after another. All three movements end abruptly without resolution.

In the Symphony No. 8 (2010–2011), the mood and textures suddenly lighten with twinkling points of brightness from the glockenspiel, playful winds, and caressing strings, if not a real tonal center that at one point dwindles down to a single line on the piano. Given Nørgård’s advanced age, this would appear to be his last symphonic word, although who knows? Increasingly we are seeing composers active into their 80s, 90s, and (Elliott Carter comes to mind) beyond the century mark. In any case, the orchestral playing and sound on these discs are top-notch, making this the obvious go-to choice for exploring in depth the works of one of our few remaining living symphonists.