The hottest ticket in many circles last weekend wasn’t the Super Bowl but Pina Bausch’s The Rite of Spring, part of a double bill of works choreographed by women and performed at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion to sold-out audiences, who were left gobsmacked by the beauty and power of dance.

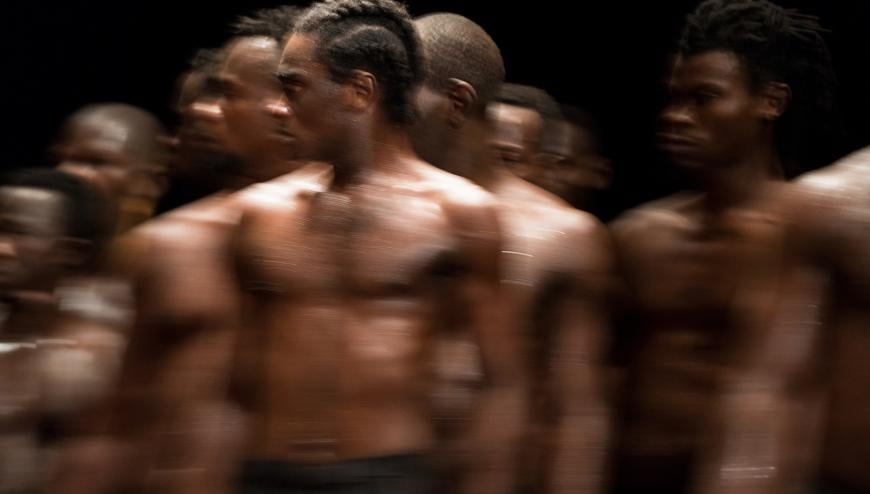

Bausch’s 1975 opus, first seen in the States in 1984, when it opened the Olympic Arts Festival in Los Angeles, featured dozens of barefooted women and bare-chested men thrashing amid tons of leaves and peat moss to Igor Stravinsky’s visceral and anarchic score. Fast-forward four decades, and the work of Bausch, who died in 2009 at age 68, is as relevant, profound, and powerful as ever, perhaps more so, as The Rite is currently being performed by 30-plus dancers from 14 African countries.

The program opened with common ground[s], a meditative 30-minute piece made and danced by Germaine Acogny and Malou Airaudo and connected to The Rite in a couple ways. A number of dancers for this Rite were trained at the École des Sables, Acogny’s school in Senegal. And Airaudo, born in 1948 and an original member of Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal, has danced the role of the Chosen One numerous times and has the Bausch aesthetic in her bones.

No ordinary curtain-raiser, the L.A. premiere of common ground[s] was a journey into lives well lived. Acogny, who turns 80 in May and has been called the mother of contemporary dance in Africa, won a Bessie Award for her performance in Olivier Dubois’s one-woman Rite, entitled Mon élue noire (My Black chosen one), which was seen at UCLA in 2018.

Acogny and Airaudo begin common ground[s] seated, their backs — still gloriously muscled — to the audience. Moving to the splendid music of Fabrice Bouillon-LaForest — a bouquet of strings with occasional ambient recorded sounds — these two dancers are nothing less than majestic. Clad in Petra Leidner’s long black gowns and sumptuously lit by Zeynep Kepekli, they make use of a few props, among them sticks, buckets of water, and several stones, Airaudo deploying the pebbles to gently massage Acogny’s back.

At one point, the pair speak lovingly of Bausch, the late choreographer’s presence permeating the theater, before singing a few bars of “Que Sera, Sera (Whatever Will Be, Will Be).” Seekers who seem to hold the answers of the universe in their agile bodies, Acogny and Airaudo, with gestures ranging from upraised arms to unison rhythmic hip-swaying, are monumental in their simplicity. Wielding sticks and ritualistically foot-stomping, the septuagenarians eventually end the work seated, as they began it, in effect proclaiming their aliveness while at the same time summoning what lies ahead. In this case, Bausch’s Rite.

Part of that Rite was the highly choreographed scenario that took place during the half-hour intermission. A crew of 14 stagehands readied the space by replacing the Marley floor with tarp, nailing it down before bringing in large steel bins filled with peat moss. Tipping these bins in split-second synchronization, the squad then shoveled and raked the stuff into place, and voila, the original set design by Rolf Börzik was ready for its part in terpsichorean history.

While history was decidedly made in 1913, when Vaslav Nijinsky’s astonishing choreography for Stravinsky’s equally scandalous score was premiered in Paris by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Bausch’s take on The Rite has proven no less shocking. And with this new iteration, the shock waves continue.

Bausch’s point of departure was the question “How would you dance if you knew you were going to die?” This notion still resonates in the restaged Rite and with even more ferocity. As the performers — 18 men in black pants, 12 women in white slip dresses — move en masse while leaping a la Rudolf Nureyev, spinning and charging the stage like marauding bulls, the earthy peat is simultaneously kicked up and clings, as it were, to their bodies.

An epic saga of human sacrifice and gender relationships, violence is in the mix as well, the separation of the sexes adding to the fear factor. Bausch’s anguished movement vocabulary is ever on display. The arms are in a constant state of downward thrusting, the act near-terroristic; the legs, stamping relentlessly to Stravinsky’s jagged rhythms, have an equally chilling effect. And did someone mention pliés? They’re in abundance, wide-stanced and emblematic of a corpus crumbling under the weight of oppression, desperation, and/or outright brutality.

This is heart-stopping, gasp-inducing theater, with the composer’s numerous motifs coming alive in the choreography, both abstract and real (notice how the women furiously flail themselves through the peat that is the earthen stage). Bausch’s Rite, a veritable combination of terror and attraction, compels on every level, especially during the authoritative circle formations. Whether moving backward or bending at the waist, these dancers make frenzied unisons look like child’s play.

Rite is also a story of sacrifice, with the role of the Chosen One performed during the L.A. run by three different women. The closing concert on Feb. 11 featured the hypnotic Khadija Cisse, who, ultimately sporting a red dress and rebelling against her destiny with unabashed rage, ended her demanding solo by falling face down in the dirt, a study in devastation.

Bausch’s choreography, primeval yet contemporary, surprising yet inevitable, is also imbued with humanity, as the power of ritual and community penetrate her movement landscape. And while there haven’t been any riots resulting from this Rite, which, with common ground[s], has been touring the world since September 2021 — and will repeat at Cal Performances in Berkeley this weekend, Feb. 16–18 — this indelible work continues to astound.