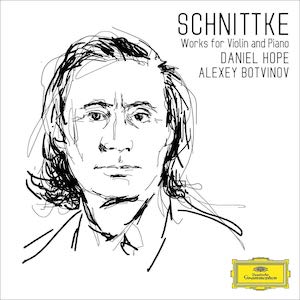

The South African-born British violin star Daniel Hope is a longtime devotee of the music of an old friend from his teen years, Alfred Schnittke. But this is the first time that he has made an entire album of the iconoclastic Russian-German composer’s violin/piano music (Deutsche Grammophon).

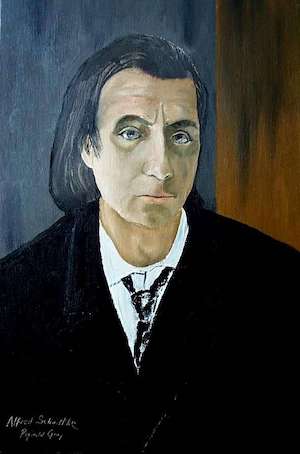

Indeed, Hope devotes the entirety of his booklet notes to a memoir of how he was instantly attracted at 15 to Schnittke’s polystylistic Violin Sonata No. 1, tried to meet him, was rebuffed at every turn until he overheard at a dinner party in Hamburg that Schnittke lived in the same apartment building. The ailing composer apparently took quite a shine to the young violinist, and they kept in touch for the next two years until a debilitating third stroke put Schnittke out of contact.

Indeed, Hope devotes the entirety of his booklet notes to a memoir of how he was instantly attracted at 15 to Schnittke’s polystylistic Violin Sonata No. 1, tried to meet him, was rebuffed at every turn until he overheard at a dinner party in Hamburg that Schnittke lived in the same apartment building. The ailing composer apparently took quite a shine to the young violinist, and they kept in touch for the next two years until a debilitating third stroke put Schnittke out of contact.

You’ll read plenty about the touching Hope/Schnittke connection and almost nothing about the music itself, while wondering why Hope waited so long to record an all-Schnittke album. He is clearly a marvelous, passionate, completely attuned advocate, in league with the Ukrainian pianist Alexey Botvinov, said to be an expert in this repertory.

The idea was to demonstrate Schnittke’s enormous range of emotions and styles –some of which got him in hot water with the Soviet authorities when he wasn’t being ignored altogether. In a press release, Hope tells of an encounter as a teenager with a former senior KGB officer in which they were talking about various rebellious Russian creative figures — the usual names. “Young man,” the officer said, “the others were legends, celebrated Soviet artists. Schnittke was nothing but a punk.”

It takes a while, though, to get to the more subversive stuff. The opening Suite in the Old Style is mostly straight Baroque pastiche — attractive, innocuous except for a handful of mischievous touches, and in its way a rebellion against official expectations for a Soviet composer. The galumphing Polka sounds like something Shostakovich could have written for a ballet or film, and the Tango is straightforward and sentimental, certainly not like Stravinsky’s mordant take on the dance.

In the Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano — which Hope previously recorded in the more abrasive version for violin, harpsichord, and chamber orchestra (Nimbus) — we hear some of the polystylistic aspects of Schnittke. There is a dissonant, despairingly spare introduction as Hope digs in incisively. Soon, the violin part gets spiky, scraping, plucking, gliding, with some jumping things in the piano part, before merging into the stern opening of a Largo in which Hope’s violin again draws blood. The finale leads off with screwball theme and proceeds with some savage humor in the violin gyrations and jazzy syncopations in the piano. Frankly, the piece makes a more provocatively spicy impression in the chamber orchestra version — especially the finale — yet Hope’s own playing cuts more deeply in this new recording.

How does Hope follow this piece? With the feathery, spare, intense Madrigal in Memoriam Oleg Kagan for just the solo violin, and another example of pure pastiche — this time in a late 18th century style — Congratulatory Rondo. The final track, Stille Nacht (Silent night) delivers the familiar Franz Xaver Gruber Christmas tune fairly straight at first, but it soon becomes something sinister and ruefully funny with deliberate wheezy discords and sleazy portamentos at the close. No peaceful night is this.

I’m reminded of Simon And Garfunkel’s similarly subversive take on “Silent Night” (from the Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme album) in which a troubling 1966-vintage newscast gradually overwhelms their sweet harmonies. Both the folk-rock duo and Hope thus end their albums the same way — hitting an easy target with a jab of uneasy sardonic reality.