As attention spans dwindle and media forms become more on-demand and digestible — think TikTok and the demise of the long-play album — some artists have reacted by producing outsized works that challenge the listener’s expected timescale. Max Richter’s Sleep is an eight-hour piece designed to be the soundtrack to an unconscious state. Ragnar Kjartansson’s BLISS, recently staged by the Detroit Opera, repeats the final chorus from Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro for a mind-bending 12 consecutive hours.

Stranger Love, a new six-hour opera by composer Dylan Mattingly and librettist Thomas Bartscherer, fits into this trend. It came to the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Walt Disney Concert Hall this weekend for one performance only; even without a convincing narrative, the playfully daring production was by turns transfixing, sublime, and ecstatic.

Rather than a conventional narrative, the opera is a colorful, transporting adventure into a human experience of the universe. Mattingly describes the work as an “experience of joy and love, of the passage of time and our undying connection as beings of stardust to the seasons, the planets, the stars.” Joy is unquestionably the overriding mood of the work; this sense of unbridled optimism is captured in the piece’s idée fixe, a unifying melody that appears throughout the work to exuberant effect.

Mattingly’s musical style is an impressive blend of the undulating, repeating soundscapes of post-minimalism (the composer has been mentored by John Adams) with microtonal harmonies — the ensemble features three microtonally tuned pianos, and the instrumental and vocal parts use microtones extensively. The composer’s original approach to microtonality, which refers to the use of smaller intervals than the steps of classical Western scales, adds a shimmering, amorphous glaze to a harmonic language that is often fundamentally tonal, and makes use of progressions that wouldn’t be out of place in an indie pop song.

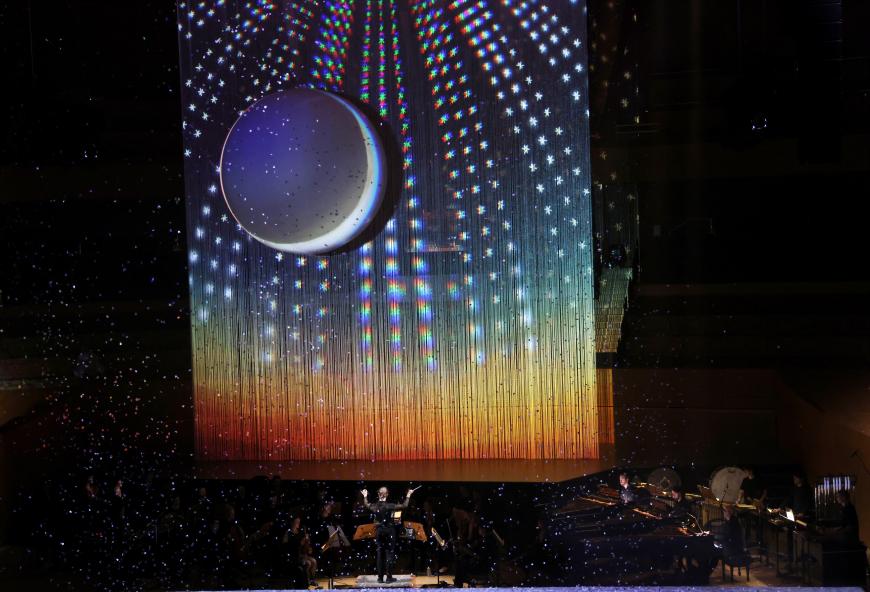

Some sections, however, verge on atonality, and the detuned pianos create a strikingly uncanny, otherworldly effect. The score is terrifyingly complex: often a repeated melody would be displaced across the conductor’s beat instead of conforming to it and the various instruments seemed to swirl around each other like one of Alexander Calder’s mobile sculptures. The ensemble was the 23-piece New York-based Contemporaneous, which Mattingly co-founded with conductor David Bloom (commanding and effective in this performance). The musicians, onstage, though barely visible from the audience, overflowed with energy and verve.

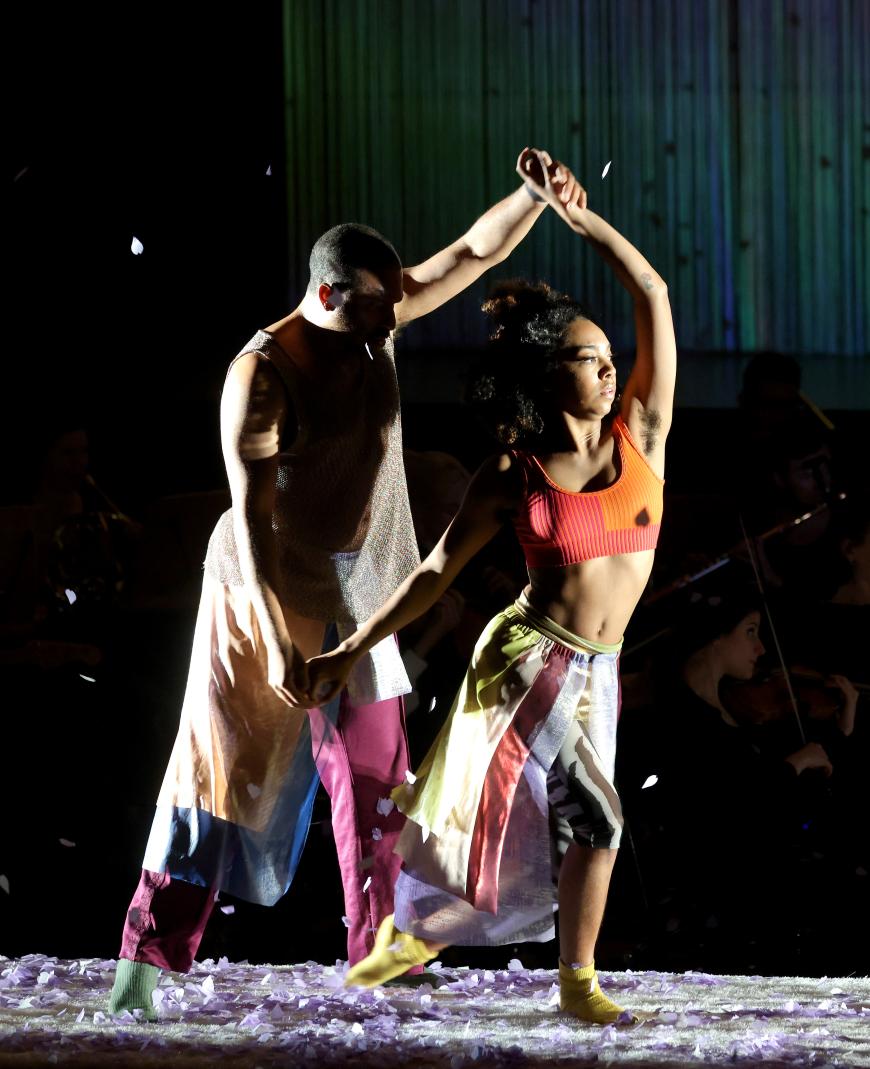

Despite the intricacy of the orchestration, there is a poppy aesthetic to the composition; the vocalists sang without vibrato and with amplification, usually a strict no-no in opera. In fact, the whole ensemble was heavily amplified, per the composer’s direction; he wanted the music to “not be heard so much as felt”. In the conclusion to the first part, the opera’s main characters, lovers Tasha (Molly Netter) and Andre (Isaiah Robinson) sing a passionate love duet over a repeated chord progression that never gets tiresome. The bass falls, the melody rises, and the vocalists soar with crystalline precision. Netter was particularly impressive, her effortlessly ornamented phrases evoking the otherworldly incantations of singer-songwriter Florence Welch.

Nevertheless, there are stretches of dissonance, capturing the kaleidoscopic variety of nature; the opening of Act II’s second part evoked Debussy’s luscious string writing; a few sections later, fast tremolos created the effect of buzzing bees.

With stage direction by Lileana Blain-Cruz, Stranger Love uses the story of two lovers, Tasha and Andre, to tell a larger story about humanity’s capacity for joy. Only the first act (nearly four hours of music) contains text; Act II conveys its drama through dance, and the 25-minute third act is entirely instrumental. This increasing abstraction is part of Mattingly’s ambition to celebrate what is common among humanity, a provocative message at a time when our politics emphasizes the specific over the shared.

The large-scale trajectory made sense, ending with a striking section that depicted cosmic transcendence. But dramatically, it was confusing. Why introduce the setting as Providence, Rhode Island and give the characters specific names and occupations, only to never reference these details again? The opening feels like the introduction to a rom-com: two people from different social spheres meet at a party and reconnect later, by chance. But the plot disintegrates as the piece progresses and the lovers pull away from each other. Andre takes a journey east to Jerusalem, returns, and reunites with Tasha. That’s not much.

Where the libretto is not incomprehensibly vague, it relies heavily on clichés: Tasha, a novelist, sings “A world away, before, beyond,/ a past that is the future: that’s what I look for/ with every page I write.” The character Uriel (a spoken part played with panache by Julyana Soelistyo) delivers a spoken introduction and interludes that are both hackneyed and unnecessary. The frequent literary allusions (“As the poet Anne Carson might say…”) could have added depth if they came from the protagonists, but in the mouth of a narrator, they were awkward, sounding like an academic essay more than drama. Most problematically, Netter and Robinson, though vocally flawless, had no chemistry as a couple. They almost never touched; in a scene where they occupy a bed together, they were shifty and uncomfortable rather than intimate.

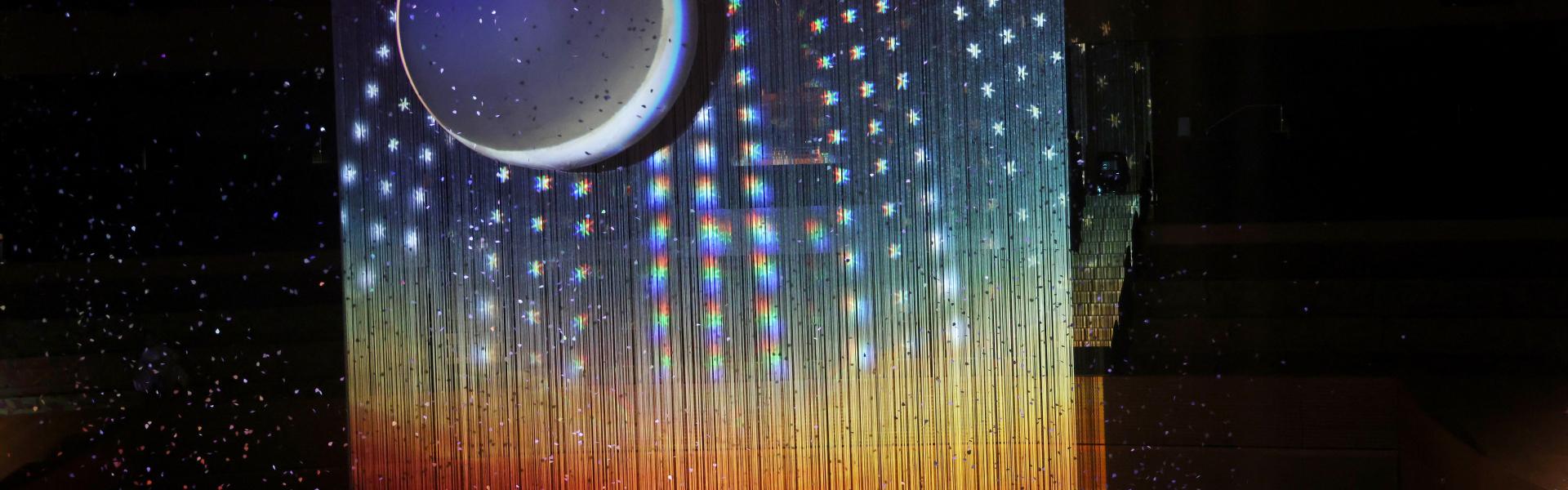

Mattingly’s dazzling music and the understated yet gorgeous production (scenic design by Matt Saunders) more than compensated for the lack of dramatic coherence. The backdrop to the stage was constructed with a sheet of dangling wires and a celestial orb; the gorgeous projections (Hannah Wasileski) turned the sphere into suns and moons as scenes of nature moving through the seasons shimmered behind.

Philosopher Edmund Burke identified vastness, magnificence, and infinity as sources of the sublime. This monumental production, over six beautiful hours, afforded the rare opportunity to get lost in a blissful, radiant world.