The sound of heavy rain can make you aware of the shape of your home; it can be grounding to feel the auditory distinction between what is sounding outside and what is sounding inside. This kind of auditory information is objective and yet can be highly emotional. We draw comfort from hearing the cold barrage outside that’s distinct from but simultaneous with a humming refrigerator or slippered footsteps in the bedroom upstairs.

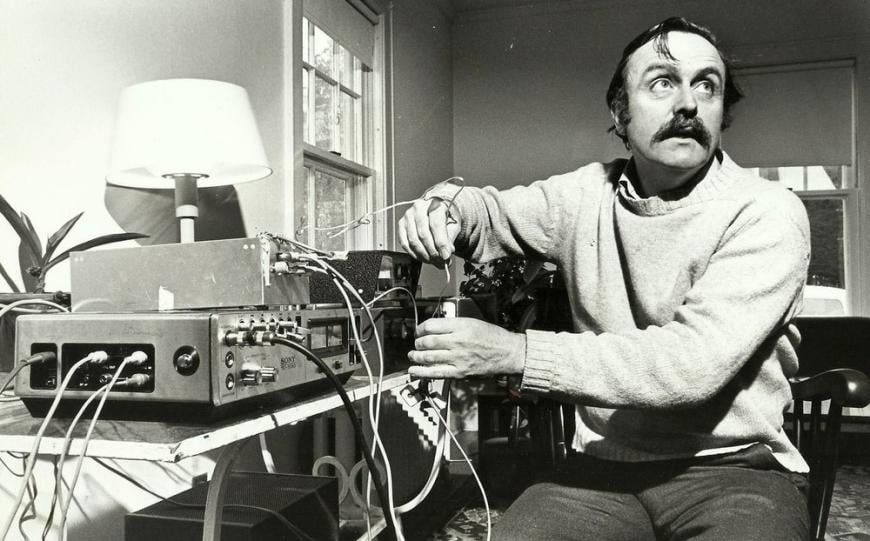

The late composer Alvin Lucier was adept at bringing forward the emotions of simple sonic experiences like this; through his deceptively simple prompts and concepts, he would lightly bring awareness to not only sonic phenomena but also the human experience of listening to them.

At the gallery and venue Monk Space on Tuesday night, People Inside Electronics, in collaboration with Brightwork newmusic, presented a succinct and sincere tribute to Lucier, who died in 2021 at the age of 90. According to performer Richard An, the pandemic stymied the production of a tribute concert earlier and now seemed as good a time as any to memorialize Lucier’s work.

PIE Artistic Director Isaac Schankler performed Music for Accordion With Slow Sweep Pure Wave Oscillators (1993), one of a handful of Lucier’s pieces that put sweeping sine tones in duet with an acoustic instrument. The emergence of harmonic anticipations, unisons, and suspensions over the slow siren of sine tones transforms this ostensibly cold and objective arc of sound into an elongated aria of sorts. Lucier often used the intersection of limited elements like this to suggest some nuanced nexus of meaning — in the case of this piece, how little impetus we need to fall into the arms of harmonic dissonance.

In staging and musical selection, PIE made important use of the gallery space, starting with a piece for vocal trio and accordion by Schankler titled Isolation Canon, performed just out of sight in the adjoining room. Defining spaces through sound is an idea that cleaves close to Lucier’s artistic center.

Monk Space is not located in the hottest commercial area of Los Angeles’ Koreatown but sits squarely in the residential buzz. The bounds of the gallery building were demarcated by ambulance sirens and gaggles of people laughing and yelling.

During the piece Heavier Than Air (1999), performers in front of and behind the audience held clear balloons to their faces and, per the simple instructions of the piece, whispered phrases starting with “I remember.” The balloons acted as a directional amplifier, such that the whispers were inaudible unless the speaker was facing you. The people outside were definitely louder than anything heard inside the building, but suddenly when one of the performers turned in your direction, you could hear, clear as if he or she were sitting right next to you, a whisper about some childhood recollection.

It was creepy and still incredibly pleasant. The gallery was only illuminated by streetlights through the windows and a light from the adjacent room. It felt very secretive — to be eavesdropping on the whispers of the performers and on the people outside. It felt like homemaking.

Like the late great Pauline Oliveros, Lucier was an exemplary prompt writer. While prose may not be the first thing you think of in relation to him, so much of his output was in the form of prose prompts for performers. For example, Duke of York (1971) is an explicit invitation to the performers to be introspective and find connections with each other.

Jen Wang’s performance of that piece, with processing by Schankler, was mesmerizing. The instructions call for the singer to collect examples of songs, texts, stories, and cultural artifacts, which the synthesizer player then processes into a collage delivered live. This act of curation is meant to draw cultural, historical, and familial ties between the performers or to enable the individual performers to realize a deeper sense of themselves.

Wang began with shushing, as if to a baby, which, through the audio processing, became a soft cloud. She moved on to a Chinese lullaby and then on to a family story her father would tell — her voice all the while echoing and scattering, harmonizing and interrupting. After the show, she explained to me that her selections, ranging from her father’s favorite aria from Puccini’s Turandot to a speech from the movie Everything Everywhere All at Once, were all connected by her own particular homesickness that stems from being the child of Chinese American immigrants. The impression I was left with was one of both yearning and warm steadiness, seeming like an act of nuanced self-soothing, an act of mourning a missed experience and making a home in its place.