Photos by Erik Tomasson

Yuri Possokhov’s Francesca da Rimini, which premiered Thursday at San Francisco Ballet, is a lush and heroic vision of a tale from Dante’s Divine Comedy, beautifully imagined. It’s set to the eponymous Tchaikovsky Symphonic Fantasy After Dante, Op. 32. In short, Francesca falls in love with Paolo, her husband’s younger brother, and since she’s already married, the impassioned couple ends up in the fifth circle of hell.

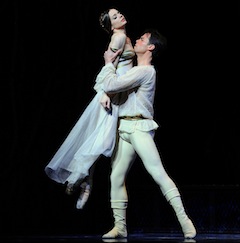

If you’ve seen The Gates of Hell (there’s a casting in the Rodin Sculpture Garden at Stanford University’s Cantor Art Center) you know what fate — presided over by the three Guardians of the Inferno that crown the gates — awaits our ceaselessly intertwining lovers, danced Saturday night by Maria Kochetkova and her Paolo, Joan Boada. The Guardians, buff grey-marbled figures in the ballet, mix into the tale of love and horror and forcefully escort the twosome to their eternal damnation.

The depth of the couple’s love, the sensuousness of its expression, and the anguish of their journey make it impossible to look away. Periodically (the audience, after all, needs a break from all this heat), it is interrupted by the indignant flouncing of five court ladies, appalled ex-friends of Francesca; her outraged husband, Giovanni (Taras Domitro), drawing no sympathy whatsoever, and those burly, vengeful Guardians (Jeremy Rucker, Quinn Wharton, and Luke Willis).

The stage, with its Italianate design by Alexander V. Nichols, is full of outburst and tumult. Let’s pause for a moment to note that choreographer-in-residence Possokhov and his principal cast are all distinguished products of Russian training from the Bolshoi (Possokhov and Kochetkova) and the National Ballet of Cuba (Domitro and Boada). The men’s dynamic leaps are a natural complement to Kochetkova’s expressive plastique, with boneless arms and extensions well beyond 180 degrees, which is a sometimes debatable virtue but worked to the story’s advantage here.

In their 10-minute pas de deux, she and Boada often seemed to move with one breath. Boada displayed elevation and power in double air turns, and as his nasty brother, Domitro seemed to ride the music as well as his own indignation in a stunning solo passage filled with crisp beats and subtle reversals of direction. Everything worked expressively and explosively together, and the orchestra, with its plangent brass and doomful percussion conducted by Martin West, was wonderful.

It was a night to be grateful for the array of gifted choreographers the company has gathered together, artistic director Helgi Tomasson not the least of them. His Trio (2011), set to Souvenir de Florence, was highlighted by its central movement, all light and shadow, danced by Sarah Van Patten, Tiit Helimets, and Vito Mazzeo, which reads inevitably and beautifully like an homage to Balanchine’s Serenade, also to Tchaikovsky. The other fine principal dancers, backed by a beautifully unified corps, were Courtney Elizabeth and Vitor Luiz in the first movement, and Vanessa Zahorian and Isaac Hernandez in movements three and four. West again conducted.

Courtney Elizabeth was a charming elephant in a pink tutu, arm curled under to suggest her trunk, in the welcome return of Alexei Ratmansky’s 2003 Le Carnaval des Animaux, set to Camille Saint-Saëns and conducted by Charles Barker.

Its charm and gentle humor rests in the understated evocations of an entire menagerie by a group of dancers who never lose their human-ness. Costuming is minimalist. The only dancer totally concealed in costume, the lion (Pierre-Francois Villanoba), loses that disguise a minute into the ballet, when he whips it off and flings it into the pit. Then he’s in overalls. The playfulness of this conceit suggests a big party. There are kangaroos and cockerels and a hen, oh my, and horses (James Sofranko and Matthew Stewart, in jockey silks), and turtles.

An exception to the minimalist costume rule is a Dying Swan (Sofiane Sylve) in full white feather, whose time-honored steps are interlaced with a few unsettlingly funny poses, which suggests that no matter how we play and disguise, ballet (or at least Fokine’s The Dying Swan choreography, which Ratmansky credits here) continues forever.