Over the last several decades, one of the pleasures of attending the San Francisco Symphony has been its music directors’ commitment to performing semistaged operas, some of which have been rarities or works that were otherwise underperformed. On June 8, the orchestra presented the latest in this series, the great Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho’s second opera, Adriana Mater, in its first West Coast production.

The performances reunited Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen and Peter Sellars, the conductor and director, respectively, of the work’s 2006 premiere. Sellars directed the 2008 American premiere as well, and Saariaho dedicated the opera to him. That Saariaho had died on June 2 at age 70 made the occasion a poignant one, especially because her daughter, Aliisa Neige Barrière, was the assistant conductor for this production.

The SF Symphony dedicated the first performance of Adriana to the composer’s memory and music. Across the street, San Francisco Opera, which next year will present the American premiere of Saariaho’s last opera, Innocence, dedicated its June 4 performance of Richard Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten to her as well.

Adriana Mater, with a French libretto by another longtime Saariaho collaborator, Amin Maalouf, deals with war, family, violence against women, the nature of manhood, and what it means to be a mother. The opera takes place over seven tableaux in two acts, in a country that is already riven by violence and on the verge of civil war. It’s immensely powerful and wrenching.

Adriana is a confident young woman with a more fearful older sister, Refka. A year before the events of the opera, Adriana danced with a young man, Tsargo. They were initially attracted to each other, but he is now a heavy drinker, and she’s not interested in him. One night, he comes to her door, claiming that he must watch for the unnamed enemy from her home’s rooftop. She refuses to admit him. He breaks in and rapes her.

In the third tableau, Adriana knows that she’s pregnant — and also that she is going to bear the child. Refka wishes that her sister wasn’t going through with this and blames herself for not having protected Adriana. Adriana wonders about the child, whose heartbeat she can sense: “Which will my child turn out to be — Cain or Abel?”

Seventeen years later, her son, Yonas, has heard rumors about his father — that he’s not the war hero, killed in battle, that Adriana told him of. After learning the truth in confrontations with Adriana and Refka, Yonas runs off to kill Tsargo.

The two men meet, and we learn that Tsargo wants to die. But then Yonas discovers that Tsargo is blind, and he can’t bring himself to commit murder. In the last tableau, Yonas, Adriana, and Refka are all reconciled, and we hear more of Tsargo’s remorse. In the end, as Yonas embraces his mother and aunt, Adriana sings, “We are not avenged, Yonas — we are saved.”

The opera employs a large orchestra, a small chorus, and electronics. Saariaho’s musical language derives from French spectralism, using orchestral color and texture as primary musical elements. The harmonic rhythm of Adriana is slow, with long pedal points in the lower strings and textures made thick by the electronics. Saariaho’s phrases are long and often pulseless, without a clear connection to the bar lines.

Throughout, the orchestra has a roiling, seething, ominous character. Snare drum, timpani, and trumpet calls herald the start of “Darkness,” the tableau in which Tsargo rapes Adriana; a riot of brass and percussion toward the end of the tableau depicts the rape itself. At the outset of “Two Hearts,” when Refka and Adriana speak of the latter’s pregnancy, the rumbling of the orchestra is profoundly disturbing. The texture lightens when Adriana says that she’s sure of nothing regarding her child, a clarinet and piano emerging from the strings to accompany her.

Saariaho styles the characters’ musical lines distinctively: quicksilver and passionate for both Adriana and Yonas, anxious for Refka. Tsargo is impulsive in Act 1 and ground down in Act 2, his musical lines at the bottom of his range and notably slow-moving, especially compared to Yonas. Adriana’s chorus, here made up of members of the SF Symphony Chorus, sometimes echoes the words a character is singing and sometimes sings wordlessly, floating atop the orchestral texture.

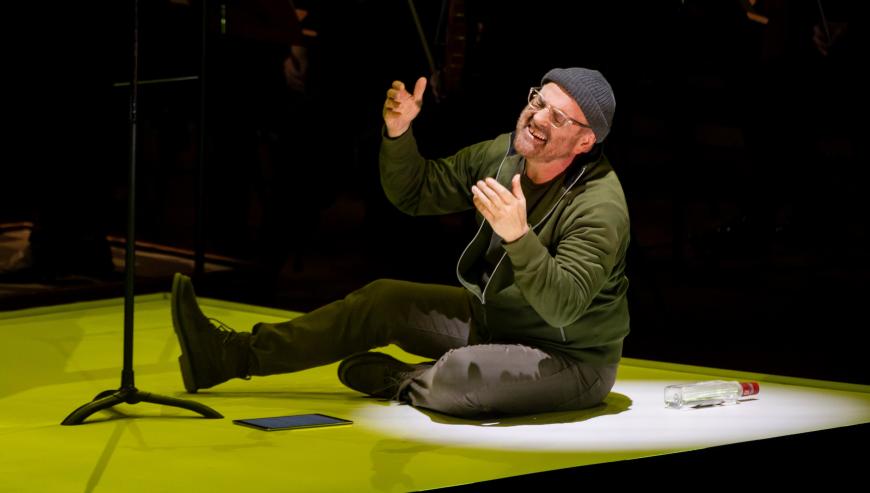

For these semistaged performances, Sellars placed two platforms at different heights in front of the orchestra and two additional platforms within the orchestra. He called for no scenery, which meant the audience could not turn away from the harrowing events of the opera.

And this was Sellars at his best, directing with admirable straightforwardness and a focus on the characters. The four platforms were on the small side, lending scenes within each tableau automatic intimacy and sometimes claustrophobia. The performers interacted naturally and with immense concentration. James F. Ingalls’s lighting shifted slowly from scene to scene and heightened the intensity of the action. The opening of the first tableau featured one platform lit in yellow, another in blue, perhaps a reference to the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The four singers, all amplified, were superb as individuals and as an ensemble. Fleur Barron’s rich mezzo-soprano and proud bearing embodied Adriana’s distinctive combination of courage and vulnerability. Axelle Fanyo brought a dark, glowing soprano to the anxious Refka. Baritone Christopher Purves’s Tsargo crumbled over the course of the opera, eaten by remorse. Tenor Nicholas Phan sang and acted brilliantly as the impulsive Yonas, who slowly matures as he comprehends the generosity and hope behind his mother’s behavior.

Salonen conducted with his customary mastery, bringing coherence and flow to the score after many years, and the orchestra played the difficult and unfamiliar music with its usual dedication and brilliance.