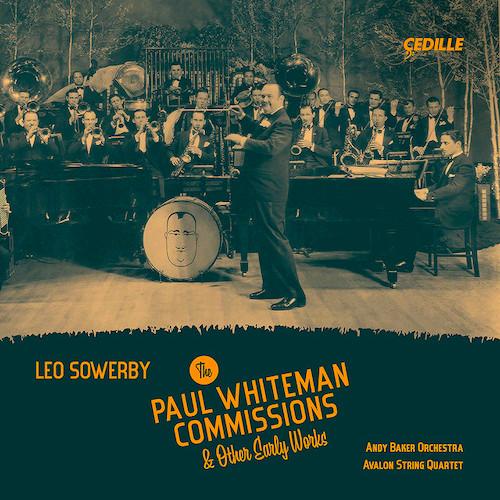

Leo Sowerby (1895 – 1968) is described in the booklet notes of a new Cedille album of his compositions (Leo Sowerby: The Paul Whiteman Commissions and Other Early Works) as “already the most frequently performed classically trained American composer” by the 1920s.

Really?

He certainly was prolific; the booklet goes on to claim that Sowerby had written some 550 pieces by the time of his death. His music was regularly played by his hometown Chicago Symphony under Frederick Stock. He even won a Pulitzer in 1946 — not that winning that prize is a guarantee of immortality. Yet his name hardly ever comes up in discussions about the leading American composers of his time.

Few of Sowerby’s orchestral and chamber works were properly published in performing editions, although most of his “church music” for organ or choir apparently was. Record catalogues from the 78 RPM era show very little action for him. One brief novelty, a flashy orchestration of the folk jig “The Irish Washerwoman,” had been recorded on 78s at least three times, which was a lot for a contemporary composition then. But there are only two more entries, and other American composers like Howard Hanson, Roy Harris, Aaron Copland, and even the now justly forgotten Harl McDonald were far better represented then. Nor did things improve in the LP era. A 1960 Schwann catalogue lists exactly three recordings of three of his compositions, and a 1967 Schwann issued the year before his death increases the total to a mere four of four.

Nevertheless, Sowerby’s profile late in the CD era seems to be on the upswing, thanks in large part to Cedille’s ongoing project of getting its fellow Chicago townsman on record. This one is centered around the two commissions that Sowerby received from the Paul Whiteman band, plus three chamber works thrown in to take the places of other proposed orchestral recordings that had to be scuttled when COVID-19 shut everything down. All except the brief Serenade for String Quartet are world-premiere recordings — which is astonishing if you believe that Sowerby was the most performed American composer of his time, and given Whiteman’s overwhelming clout during the ’20s.

It was 1924, and Whiteman was revving up his campaign to “make a lady out of jazz” with full-blown concerts of commissioned pieces. The first concert, “An Experiment in Modern Music,” happened to yield Rhapsody in Blue, and in December, Sowerby’s first Whiteman commission, Synconata, landed at the Metropolitan Opera House. I think it’s delightful — a viable fusion of jazz elements winningly integrated into a one-movement, 11½ minute classical structure. It’s not as sassy as Rhapsody in Blue gets, but like Gershwin’s piece, it has a memorable earworm that dominates the music from the middle onward. I wonder if Sowerby was aware that his tune had been hijacked in 1966, knowingly or not, by Cy Coleman in “If My Friends Could See Me Now” (from Sweet Charity).

The success of Synconata led to another, more substantial Whiteman commission the following year, a four-movement Symphony for Jazz Orchestra with a self-inflicted wound of a title, Monotony. Actually “monotony” is a reference to Sinclair Lewis’s character Babbitt, whose conformist daily life the symphony is supposed to track

This is a “jazz symphony” that shouts Roaring ’20s, beginning slyly with muted trumpet, bass clarinet, sliding horns, and saxophones making weird comments before a saucy tune launches the opening movement. Later on, there is a sermon at church with a tango gait, and a finale that dares to call itself “Critics,” a successor of sorts to Richard Strauss’s caricature of us in Ein Heldenleben (A hero’s life), in which Babbitt goes to a concert and later reads the reviews from six music critics. Of course, Sowerby’s satirical jabs are more fun — like when a jazz band is interrupted by harumphing comments from the “critics.”

The Andy Baker Orchestra manages to replicate the mellow timbre of the Whiteman sax section and revels in the symphony’s Jazz Age syncopation. Yet what this piece needed, perhaps, was Ferde Grofé, if not Sowerby himself, to inflate and convert the Whiteman band instrumentation to that of a full symphony orchestra, as he did for Rhapsody in Blue. That way, the piece might have stood a better chance of entering the repertory, whereas the Whiteman sound instantly dates it as a curiosity.

As played by the Avalon String Quartet, the Serenade for String Quartet is a tuneful, bucolic early work that helped put Sowerby on the map. Tramping Tune, with pianist Winston Choi and double bassist Alexander Hanna added to the Avalon foursome, is another early piece with a folksy flavor that overly reminds me of Sowerby’s sometime mentor, Percy Grainger.

The String Quartet in D Minor has a first movement that takes in the blues and a genteel degree of ragtimey syncopation, while the rest continues in the tuneful, flowing language of the Serenade. This one hasn’t been performed at all since 1937, and the main reason I can see — besides being out of fashion — was the lack of a printed edition (indeed, the Avalon Quartet, as well as Andy Baker, had to scrounge and labor before they were able to perform any of this music). Why Sowerby didn’t get around to making performing editions of his symphonic and chamber works is unclear. Maybe with 550 pieces to write, there simply wasn’t enough time.

If this CD makes you want to explore other facets of Sowerby’s massive, mostly-untapped catalogue, check out Cedille’s earlier 2021 releases — a double-album by organist David Schrader that contains one disc of Sowerby’s organ pieces and another of music by Fred Ferko, and the Lincoln Trio’s rendition of the serious, expansive Piano Trio No. 2 from the CD Trios From the City of Big Shoulders.