He looked small behind his computer after being helped into his chair and said nothing before he began. The reverence in the room was palpable. Electronic and multimedia composer Morton Subotnick has had a performance career spanning a dizzying amount of time and many revolutions in technology and musical style, all of which he seems to have folded into his practice.

Subotnick is 90, and this was most likely his last public appearance in his birthplace of Los Angeles, though in the past few years his performances have all been billed as “perhaps” his final run. And yet, here we are again, witnessing the wizard who co-founded the San Francisco Tape Center and commissioned Don Buchla to create the now-legendary Buchla modular synthesizer in 1963, the composer who was a founding member of the California Institute of the Arts in Santa Clarita and whose Silver Apples of the Moon (1967) was a surprise hit for Nonesuch Records and the first fully electronic work commissioned by a record label.

Presented by dublab and 2220 Arts+Archives for the California Festival and continuing on tour this week as part of Other Minds Festival 23 in San Francisco, Subotnick and German video artist Lillevan’s As I Live and Breathe, Version 3 is a piece that Subotnick describes as his last performance work and a “musical metaphor for my life in music.”

The core of this piece, premiered in late 2019 as part of the Recombinant Festival, is delightfully literal. It begins with the sound of Subotnick’s breathing — mic’d close with a headset, uncomfortable and ragged — which slowly proliferates into a variety of sound landscapes. His breathing, the most basic evidence of life, triggers processes throughout the work, and there is something comforting, even humorous, about the simplicity and directness of that premise.

The first section of the 45-minute piece is achingly quiet, fragile. The labored sound of breath is sparse, and you have to concentrate to catch the wisps of sine waves, the blips and breezes surrounding the raw whispers of breathing. Silences are thick and uncomfortable. Change is glacial.

But somehow the music arrives naturally at its first peak, a cacophony of little vocal sounds, both prerecorded and live, that swarm and transform their little awkward shapes. It was hard not to giggle at the odd, almost embarrassing sounds of surprise, throat clearing, and noises you might make in frustration trying to open a pickle jar — old-man sounds all jangling around in a jar like coins.

Subotnick has perfected the sound of natural proliferation, which might be surprising to someone who has not spent much time in the land of electronic music. From the early days of synthesizers, people like Subotnick have used synthesis processes to create sound that, while not “naturally” made, can behave in natural ways. It is a wondrous thing, the way that the sound of evolution — growth, change — is somehow hardwired into the roots of electronic music.

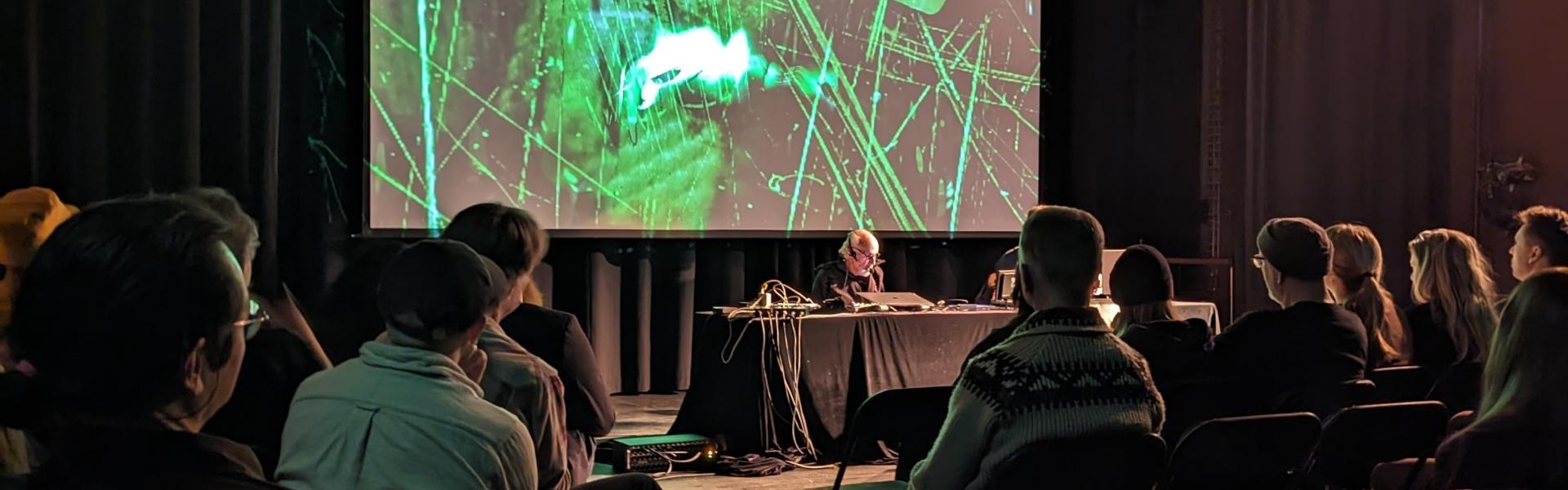

Lillevan’s live video at the first climax changed from a space-like gray scale to a lush green, mirroring the almost insect-parodying liveliness of the music. The video of constantly manipulated abstract shapes and lines moved through different color palettes in accordance with the sections of the piece.

Despite these moments of consonance between the video and the music, the combination of the two was not always easy. Lillevan’s creations are stunningly complex, with a huge range of evolving textures. This could also describe Subotnick’s music, but for large portions of the piece, both mediums were competing for the audience’s attention. I had to close my eyes to listen because the video was too visually loud. These two artists, who have been collaborating for over 10 years, are a great match in spirit, but in this version of the piece, the patience in the music and the intense quietude of the opening were drowned out by the visuals.

The mesh of video and audio improved at the end of the work, as popping sounds (like hitting a sibling with a wrapping-paper tube) danced in circles around the surround-sound speakers in the hall. A feeling of great depth and lightness brought a giant lasting smile to my face, and after the piece ended, I felt disappointed that there was not another hour to enjoy it.