Gustav Mahler never lived to hear a performance of his last completed symphony, the Ninth — and that stark fact, along with the extraordinary emotional impact of the music, has reinforced the legend that this is a farewell statement, haunted by Mahler’s diagnosed heart condition. It turns out that this was a passing phase, for a Tenth Symphony headed in new directions was under construction when the composer died.

Still, the notion of farewell persists. Leonard Bernstein thought so. Bruno Walter’s urgent performance with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1938 has been interpreted as a farewell to a free Austria less than two months before the Anschluss. The great jazz tenor saxophonist Stan Getz told me that he was listening to Mahler’s Ninth a lot as he battled the cancer that would take his life a few months after our conversation.

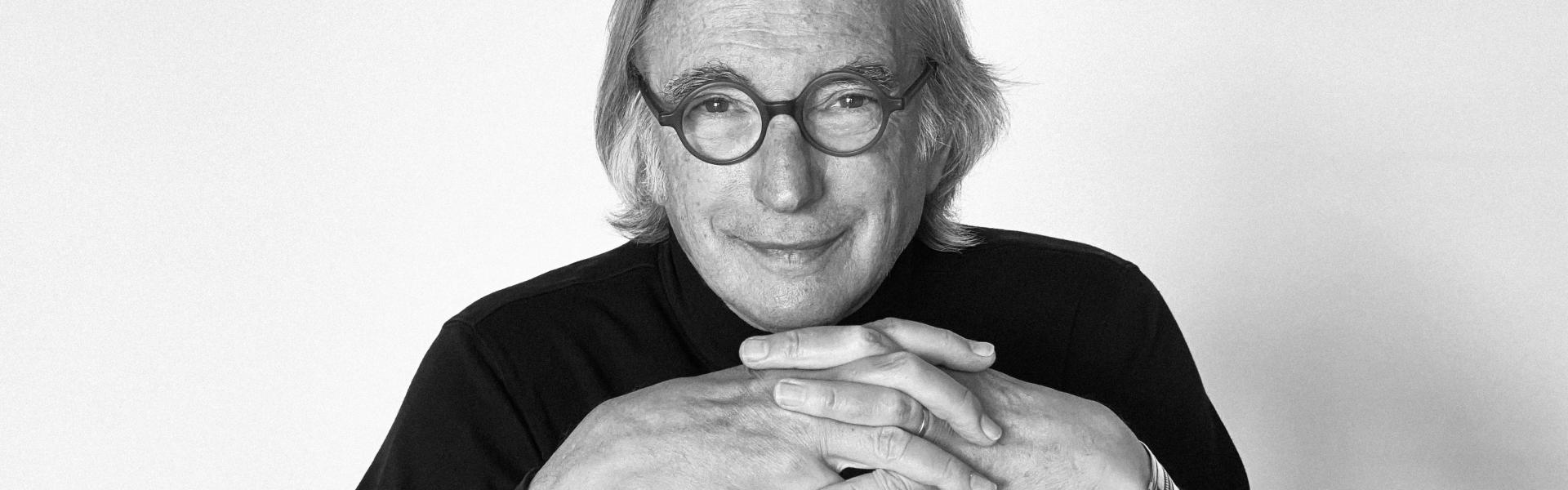

At a certain point in life, whether circumstances are personal or environmental, it may seem to be tempting fate to contemplate Mahler’s Ninth. But Michael Tilson Thomas, who has his own view of what the symphony means — he calls it a self-portrait in the composer’s mind and those of others who misunderstood him — is not afraid. Wrapping up his annual winter appearances with his hometown orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, on Sunday afternoon (Jan. 15), Tilson Thomas returned to the Ninth with the most daringly drawn-out performance that I’ve heard from him — or anybody — yet.

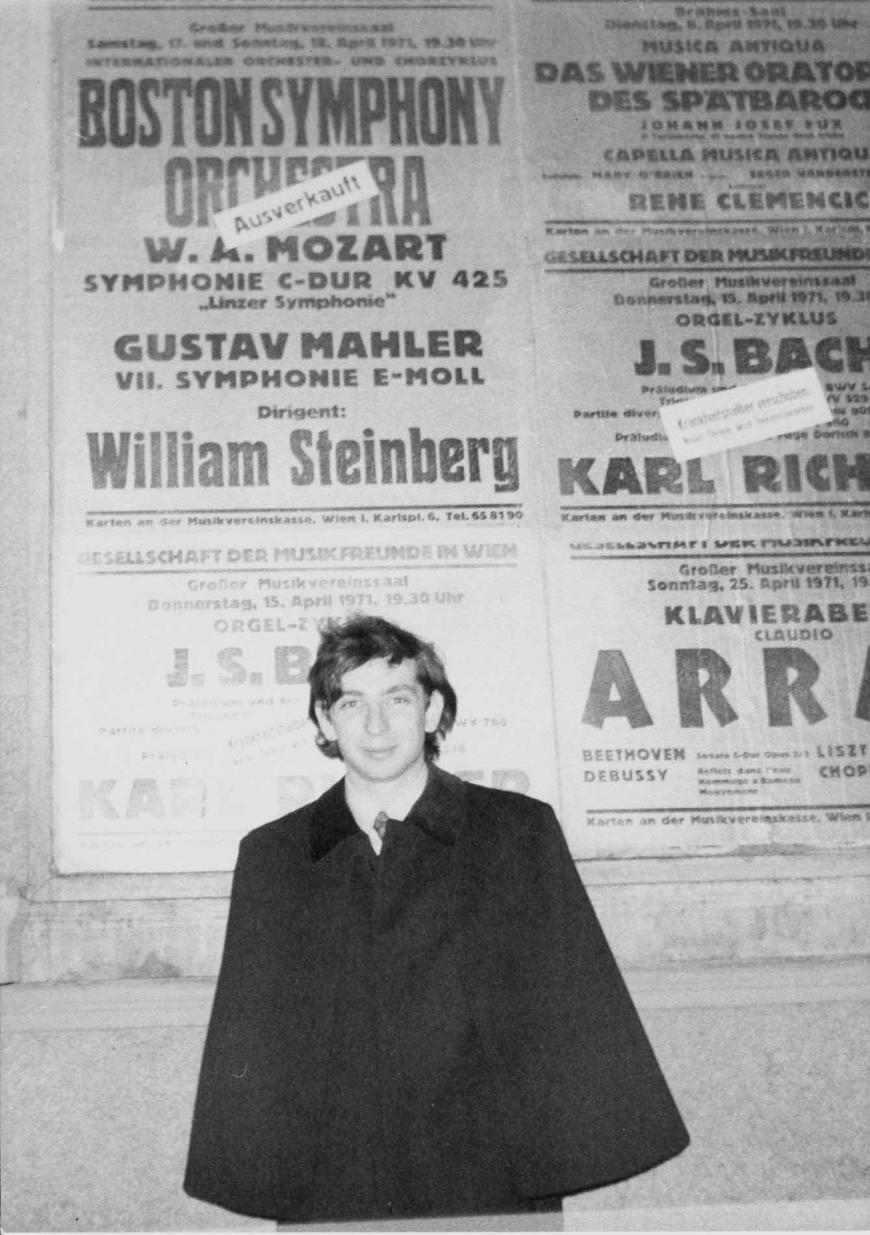

MTT has experience with Mahler’s Ninth dating back half a century. It was on the program in his first encounter with the San Francisco Symphony in 1974. Three decades later, he finally recorded it in a 2004 live performance with the SF Symphony, a broadly eloquent, heart-stopping, beautifully engineered rendition that has retained its initial impact upon further listens. I heard him repeat the performance on tour with SFS the following year at Walt Disney Concert Hall, and it involuntarily became the last piece of music that he would lead as SFS’s music director, in performance at the Mondavi Center in Davis on March 7, 2020, just before the COVID shutdown.

While MTT’s 2004 recording was slow enough, his rendering on Sunday stretched out to a bit over 94 minutes, longer than all but one of the plethora of Ninth recordings (that of Eiji Oue) listed in Péter Fülöp’s exhaustively encyclopedic Mahler discography. If you count the pauses between movements — which I didn’t — it might have been the longest, period.

Of course, it’s what you do with all of that expanded real estate that counts — and Tilson Thomas spent his time painstakingly, lovingly, subjectively caressing every detail of Mahler’s contrapuntal design. Whereas in the previous week’s concerts, MTT used a conventional violins-left, cellos-and-basses-right orchestral layout, for Mahler he reverted to the split-violins, cellos-and-basses-left-center seating that Gustavo Dudamel and Esa-Pekka Salonen use in Disney Hall — which gives a more robust bass response.

The tremendous climaxes in the first movement that Tilson Thomas held out at length in San Francisco were stretched even further here before achieving denotation. The mood was somber, and MTT kept things moving inexorably forward, sometimes barely hanging onto the thread of the line yet making it all cohere. The second movement was done pretty much as before, moderately slow in pacing as Tilson Thomas maintained a just-firm-enough ländler rhythm. The Rondo-Burleske trundled along in no hurry at all with a weighty big-orchestra sound; the central section, which MTT claims is Mahler proclaiming who he really is, was played molto appassionato, pulling out all the emotional stops.

Ultimately, it was the meditative fourth movement that benefitted the most from a broad pace. Bernstein considered it the ultimate of farewells, pacing it slower and slower as he grew older, whereas Walter found a stoic, life-affirming strength in this music in his refusal to dawdle. Setting a not unreasonably slow tempo, MTT maintained tension in the line while leaving phrasings alone so that everything flowed naturally, lushly. The final Adagissimo page in the score was as still as he and his rapt orchestra could manage, transcendent in its suspension of time.

Given Tilson Thomas’s ongoing fight to keep glioblastoma at bay, he thankfully displayed no obvious diminution of stamina on the podium. Indeed, he seemed more energized than in several recent appearances here, even executing a small leap at the end of the Rondo-Burleske that brought back memories of the young MTT we knew in L.A. back in the day.

In fact, there was a spaciousness and weight about this performance, most noticeably in the middle movements, that put one in mind, perhaps incongruously, of former LA Phil Music Director Carlo Maria Giulini. And why not? MTT served as LA Phil co-principal guest conductor during Giulini’s years here, and maybe there is a little-noted kinship there.

We should cherish whatever time Tilson Thomas is going to spend in Los Angeles in the future — and the good news is that he plans to be back next season for at least another week with the LA Phil. In the meantime, he is scheduled to keep going with upcoming conducting dates in San Francisco, New York, Cleveland, and Zurich through June. His resilience is inspiring.