Omar, the Pulitzer Prize-winning opera by Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels, opened at San Francisco Opera on Sunday, Nov. 5. The first performance sold out, and the beautiful production, strong cast, and attractive music give the opera broad appeal. Moreover, it arrives at a moment when laws are being considered in some states to suppress public schools’ ability to teach their students the terrible history of slavery in this country. Omar couldn’t be timelier. But despite the excellence of the performances and the beauty of the design, the opera has some structural flaws that ultimately limit its effectiveness.

Omar is the second of three SF Opera co-commissions in the 2023–2024 season, and like Mason Bates’s The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, it’s based on the life of a real person. Omar ibn Said, born around 1770 in the African region Senegambia, grew up in a well-off family and became an Islamic scholar. Around 1807, he was kidnapped, taken to the U.S., and enslaved. He left a number of documents at his death, including letters and a memoir, the only known autobiography by an enslaved person that’s written in Arabic.

Spoleto Festival USA asked Giddens, a songwriter, MacArthur Fellow, and member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, to write an opera on Omar’s life and partnered her with Abels, a composer best known for scoring director Jordan Peele’s films. Giddens wrote the libretto; she and Abels wrote the score together.

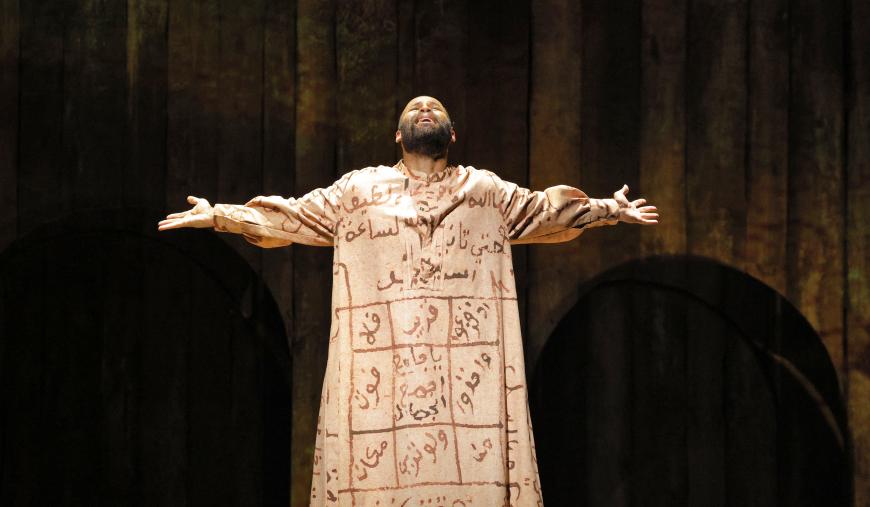

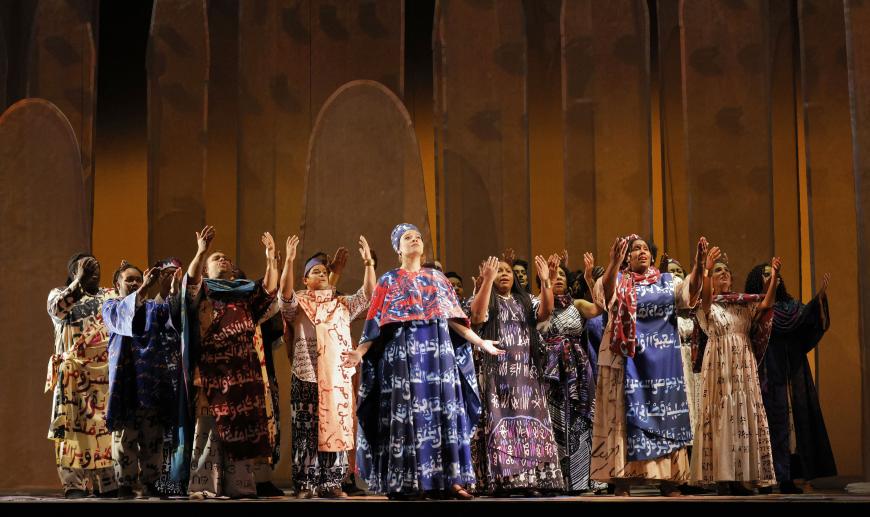

The opera opens in Africa, signaled by a variety of percussion, drones, and sinuous melodies in the orchestra. The production design matches the sound world with projections of West African architecture. April M. Hickman and Micheline Russell-Brown’s striking costumes are cut like traditional West African clothing, and the textiles are printed with texts in the Arabic, English, Ngwe, Bamum, and Vai languages, representing the importance of words in Omar’s life. Amy Rubin’s beautiful set designs include the dramatic use of fabric draperies, trees as stage elements, and ships represented by graphics of slaves packed in holds.

Over the course of the opera, you hear more African-style music, bluegrass, gospel, blues, “churchy music” (Abels’s phrase), Islamic chant, and Appalachian folk. As Giddens says in her program note, “Black musical creators from my musical lineage are shot through a score that is nevertheless firmly situated at a crossroads of the folk and western classical traditions.” The score doesn’t use folk instruments; there’s no banjo or guitar in the score, though you might occasionally think there is.

Giddens and Abels have created a score that’s eminently singable, even at its most operatic, without demanding vocal extremes from the performers. They set the text naturally and melodically. Omar is very much a number opera, song-oriented and often with the kind of rhyming stanzas you’d find in a folk or pop song. There’s a good deal of choral music, much of which sounds more vernacular and less formal than what you usually hear on this stage. The subset of the San Francisco Opera Chorus that sang here was as sonorous and committed as could be.

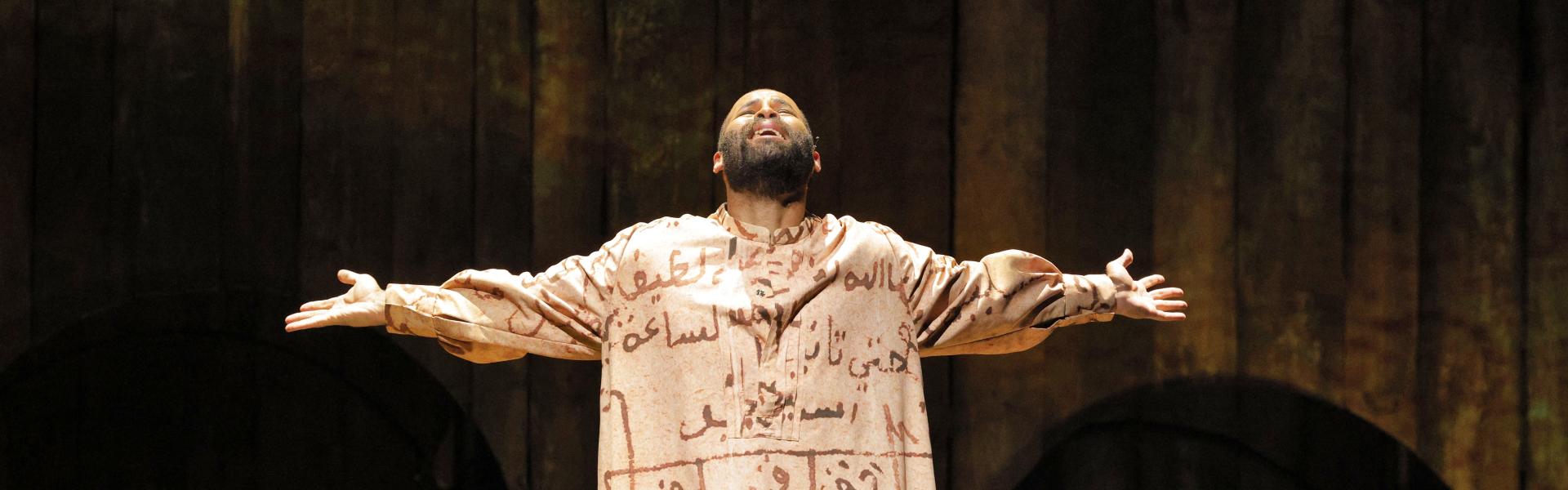

In the title role, Jamez McCorkle, making his SFO debut, gives a commanding, visceral performance, singing with a smoothly baritonal tenor. He’s onstage for nearly the entire opera and maintains a ferociously concentrated presence throughout. His Omar has something of a protective shell about him, a refusal to submit even when he is thoroughly trapped by a cruel enslaver. He is exposed to the full range of brutality and insults to which his people were subjected, from the horrors of the Middle Passage to being treated like property to being regarded by enslavers as less than human. Whatever Omar doesn’t experience, he sees.

The world of the opera is a world where the spirits of ancestors communicate with the living. Omar’s mother Fatima, sung by the radiant mezzo-soprano Taylor Raven, died in the raid when he was kidnapped, but he feels her watching over him. Throughout the opera, you see glimpses of a vividly dressed dancer, Jermaine McGhee, swirling gracefully in the background as the Ancestral Figure.

Omar is first sold to a cruel and evil man, Johnson, but encouraged by Fatima’s spirit, he escapes. He is eventually recaptured and sold to the comparatively benevolent Owen. The sonorous, handsome bass-baritone Daniel Okulitch sings both characters, reminding you that, regardless of the details of his behavior, an enslaver is still an enslaver.

Moreover, Owen buys Omar because his young daughter, Eliza (the bright-voiced mezzo Laura Krumm), enchanted by Omar’s writing, begs her father for him, much as she might beg for a puppy. Yes, that did make this reviewer’s skin crawl, as did many other details of how enslaved people are treated as the plot unfolds.

The second act is the weaker of the two and contains two missteps, one of musical tone, one in the structure of the libretto.

At Owen’s plantation, Omar meets Julie, who escaped the Charleston slave market and fled back to a better, though still enslaved, life. Julie, gorgeously sung and acted by the charismatic soprano Brittany Renee, tells Omar about her parents and that her father was a Muslim. But the music she sings, and the orchestration, suggest seduction or flirtation, not an interchange about family and religion. What you see doesn’t match what you hear, leaving you scratching your head.

In the last couple of scenes, the opera turns into an oratorio as the libretto runs out of steam. Omar’s beautiful and uplifting analysis of the 23rd Psalm is a musical climax that makes you think the opera has just ended, but there’s another 15 minutes left.

Omar’s exceptionally big cast allows many singers a few solo lines. Among them, tenor Barry Banks stood out as an auctioneer and Owen’s friend, Taylor. Mezzo Rehanna Thelwell showed fine comic timing in her scenes with Julie, and soprano Sydnee Turrentine-Johnson had a showstopping solo at the beginning of Act 2. Conductor John Kennedy, making his SFO debut, had a sure hand with the score.

Kaneza Schaal directed with a fine eye for symmetry, balance, and movement. She also contributed a powerful program note about the place of slavery in America and why we must hear stories like that of Omar ibn Said. Performances run through Nov. 21.