Cal Performances closed out its Illuminations: “Human and Machine” series with two performances of Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower, an opera by Toshi Reagon and Bernice Johnson Reagon. Butler’s grim dystopian novel includes any number of the elements that you find in opera: a young person set apart because of her special abilities, a community under siege because society at large is falling apart, family conflicts, a journey of discovery.

Butler was a giant, one of the few Black science fiction writers of her generation. She died much too soon, in 2006 at age 58. The Reagons started to work on their opera in the late 1990s, soon after Parable of the Sower was published, but the completed work wasn’t performed until 2015.

Butler set her novel some 30 years after its 1993 publication date. With 2024 only months away, it’s scary how prophetic Parable of the Sower and its sequel, Parable of the Talents, are. The world depicted in the novels, marred by social disintegration, deep racism, material scarcity, collapsed and ineffective government, environmental disaster, and widespread violence, draws ever closer.

The bones of the story are uncomplicated. Lauren Oya Olamina, Black, 15 years old, and daughter of a preacher, is a super-empath who shares the emotions and physical experiences of people around her. She hides this ability because of how vulnerable it makes her in a chaotic world. She is also acutely aware of the collapsing society around her and prepares for the day that she might have to leave her home in Southern California in a hurry.

She’s also developing what she calls Earthseed: The Books of the Living, philosophical or religious writings that support a particular vision of community, a community where people care for each other and aim to eventually leave the earth and establish homes elsewhere in the universe. Lauren is a visionary and a natural leader, and when the small community she lives in is destroyed, she and two people she knows, Harry Balter and Zahra Moss, walk north toward what they hope will be a better life in Oregon or Washington or even Canada.

Along the way, they pick up more refugees and form a community in motion, looking for better things in a world where owning a gun and setting overnight watch rotations can save your life. They see cannibalism, fire, random gang attacks, and enslavement but also find decent people trying to help each other through terrible times, people who are drawn in by Lauren’s vision. For all the horrors it recounts, Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower ends on a note of hope.

The opera that the Reagons have produced is remarkable in every way. Written for amplified singers and a chamber orchestra of violin, cello, acoustic and electric guitars, electric bass, keyboard, and percussion, the songs that make up the opera are in a wide variety of Black American vernacular styles. Blues, gospel, folk, and funk all make their toe-tapping appearances, right alongside a few numbers incorporating traditionally “classical” techniques in the strings.

Harmonics and pizzicato land with eerie force, coming from a different musical world from most of the opera. Some vocals are highly melismatic and decorated, sung with improvisatory, jazzy freedom. One of Lauren’s songs twines itself plaintively around a single ostinato note in the violin.

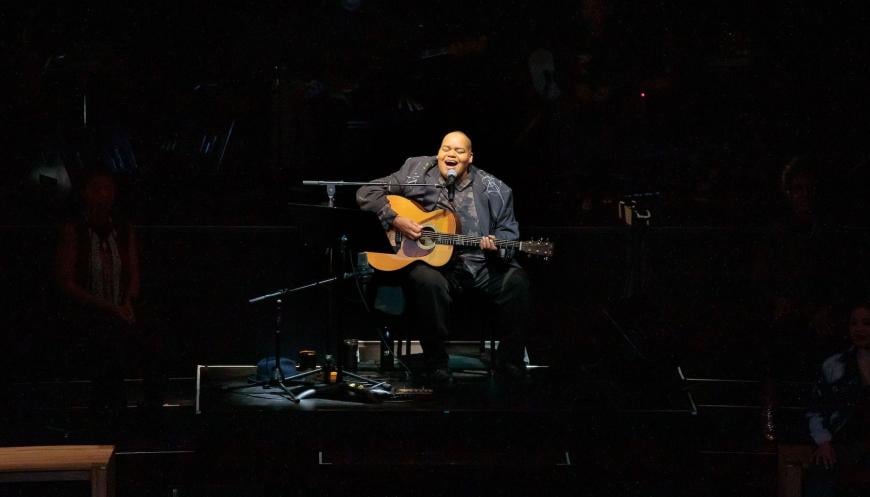

The opera juxtaposes the fictional characters and story with three Talents who sit on a center-stage platform and comment on the action without participating, acting as a Greek chorus. One of these was Toshi Reagon herself, playing guitar and sometimes speaking directly to the audience about politics and current events, sometimes teaching the audience the chorus of a song or where to clap in the next number and inviting us to participate. This back-and-forth between performer and audience had the feel of a folk concert and a church service; you truly felt that you were participating in, rather than just observing, the opera.

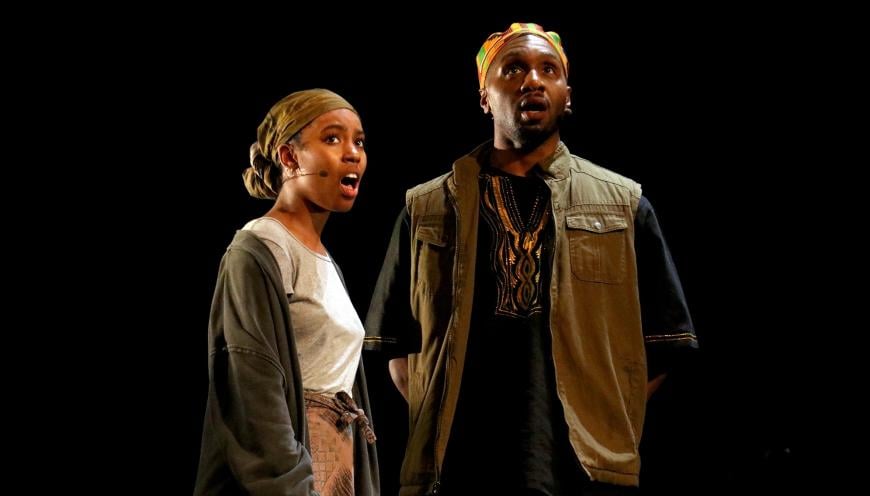

Most of the action of the opera, which was co-directed by Signe Harriday and Eric Ting, took place on the front third of a stage on which there were few props and virtually no scenery. Interactions among the characters were clearly wrought, and there was a good sense of how the characters move through the world. All credit to choreographer Millicent Johnnie and movement director Yasmine Lee for the strong physicality of the opera.

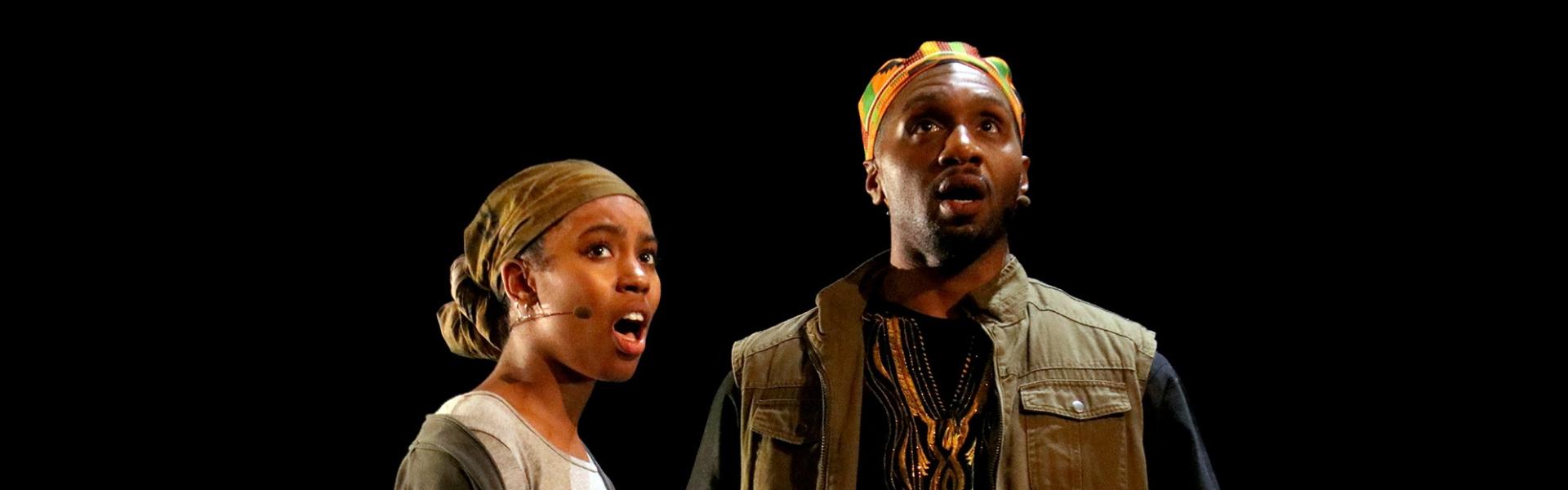

As Lauren, Marie Tatti Aqeel held the stage brilliantly, from her first appearance scribbling in a notebook at a corner of the set. Though slight, she moved with tremendous, eye-drawing authority. Noah Virgile was a sweet presence as Harry Balter. Afi Bijou brought a delicate fragility to Lauren’s stepmother Cory, and Neil Dawson was a mellifluous Reverend Olamina, Lauren’s father. Isaiah Stanley made a vivid, violent Keith, Lauren’s half brother, an immature youth who mistakenly thinks he’s a grown man. The excellent cast also included Toussaint Jeanlouis, Be Steadwell, Alex Koi, Josette Newsam, and Evie Schuckman. All except Aqeel, Virgile, and Alina Carson (as Zahra) played two roles.

Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower is a powerful, moving, and engaging work with just a few weaknesses. Even with amplification, only about a third of the words came through; supertitles and a more complete synopsis would have clarified the specific songs and the overall plot. And if I hadn’t read Parable of the Sower recently, I wouldn’t have been able to follow the story at all because the libretto, which Cal Performances was able to provide to me, touches on different aspects of the plot without explicitly narrating each event depicted. Nonetheless, if I hadn’t been committed to a different event, I would have tried to get a ticket for the second performance, and if there were a recording of this marvelous opera, I’d buy it in a heartbeat.