Dido, queen of Carthage, is at the center of any number of operas owing to the intense drama of her story. Widowed at an early age, founder of a great city, resistant to remarrying, she falls in love with Aeneas, son of a goddess, who has fled the fallen city of Troy and taken refuge in Carthage. He’s on his way to found the city of Rome, though, and after he leaves Carthage, she commits suicide.

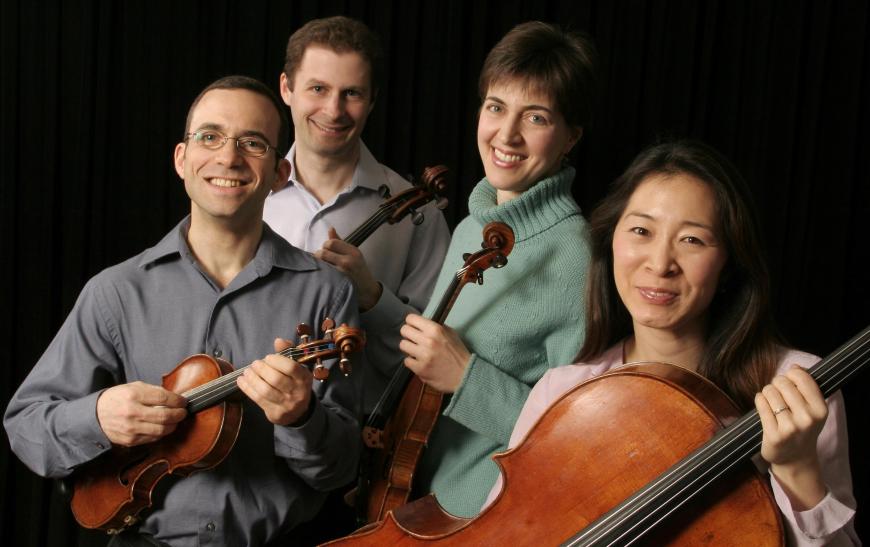

The story is the basis of many an opera, ranging in scale from Henry Purcell’s tiny Dido and Aeneas to Hector Berlioz’s gigantic Les Troyens. Composer Melinda Wagner and librettist Stephanie Fleischmann have now created a monodrama, Dido Reimagined, that specifically responds to “When I am laid in earth,” Dido’s closing lament in Purcell’s opera. This work was created specifically for soprano Dawn Upshaw, an important performer of music new and old for nearly 40 years, and the Brentano String Quartet.

The first half of Thursday’s concert was ideally programmed to introduce Dido Reimagined. It consisted of lute songs by Purcell, John Dowland, William Byrd, and Robert Johnson and “When I am laid in earth,” interspersed with movements of viola da gamba consort music by Purcell, Matthew Locke, and Thomas Tomkins. All these works were idiomatically arranged for string quartet. The lute songs chosen were by turns charming, bawdy, or melancholy. Upshaw’s sense of timing and phrasing is as acute as it’s always been, but her vibrato has loosened with time, and high notes in these selections came with less ease than one might hope to hear.

Owing to a mix-up, San Francisco Performances didn’t have the printed text of the libretto available at the concert. During the performance, Upshaw’s diction conveyed perhaps 10 percent of the text, and so this reviewer’s notes on the music and its general shape aren’t fully connected to the libretto and the story it’s trying to tell.

“When I am laid in earth” takes up a scant four lines totaling 22 words. The title and subtitles of Fleishmann’s libretto are nearly that long and tell you what it’s not: “Dido Reimagined / a response to Purcell’s ‘Lament’ / (not a threnody; thanatopsis; taps; keening; ululation; obsequy; dirge; elegy).”

Upshaw, Wagner, and Fleischmann were united in a vision of Dido in which she didn’t commit suicide. Fleischmann’s libretto, nearly four pages long and starting with four epigraphs, is in five parts. Starting off with “end of summer,” it proceeds in numbered sections through the four seasons to the following summer.

“End of summer” depicts Dido fleeing by various means of transport from, presumably, being dumped by Aeneas — by lobster boat, by stolen car, by bus — eventually alighting on an island, where she remains. After that, there’s not much action or drama, although the libretto does recount the story of Jupiter, Callisto, and Juno during “winter.” Dido recalls her life, wanders the island, and observes nature, finally concluding, “But no. Dead or alive, Dido knows: / She is love. / She is love.”

Although Fleischmann is an experienced librettist, the text isn’t structured in ways that suggest a strong dramatic arc. Wagner is left to bring most of the drama to Dido Reimagined. She has not previously written an opera or dramatic work, and it does show.

The music Wagner sets the text to is attractive and often beautiful, and the Brentano played it magnificently and with total commitment. The composer takes advantage of every technique available to string players: harmonics, pizzicato, different ways to bow. Early on, the singer gets a mini-rage aria. The music has plenty of variety, and Upshaw sounded far better here than in the first half, but ultimately there’s not much of an audible dramatic arc to the monodrama. I did not have a strong sense of where sections began and ended, what the most important parts were, or how Dido’s life after Aeneas progressed. Wagner and Fleischmann’s Dido is rather bland, with nothing like the rapt intensity of Purcell’s or the noble rage of Berlioz’s — or the outsized emotions of most operatic heroines.