Rafael Payare may have had a late start as a conductor, but once he got going, his profile zoomed upward. When he came to the long-underachieving San Diego Symphony in 2019, he pulled the orchestra up in short order as well. Indeed, with the recent announcement of November’s California Festival, the SDSO was granted equal billing with its mighty colleagues to the north, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the San Francisco Symphony. That’s what the influence of one charismatic, talented musician can do — allied with a most encouraging management team in San Diego.

Over the weekend, Payare, a onetime Dudamel Fellow, returned to Los Angeles as a guest conductor, and May 11–13, he’ll visit the SF Symphony for the first time. To sum up his Sunday afternoon, April 16 date with the LA Phil: He lit a fire under the orchestra with his weaving, swaying, extremely physical manner of conducting. Perhaps the flames burned too hot in spots, but one can’t deny that the results were very exciting.

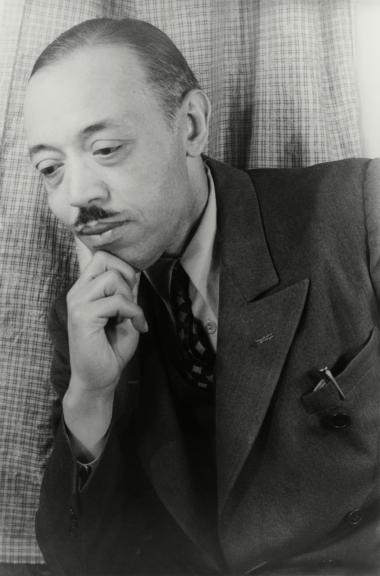

First came another newly resurrected item from the prolific oeuvre of William Grant Still, a 10-minute symphonic poem called Darker America. (It’s also on Payare’s San Francisco program.) It’s an earlyish work for Still, circa 1924, yet his sound and manner are there, the mixture of European tradition with ever-so-slightly bent notes and a touch of sass deeply rooted in the blues.

Yes, the title gives the premise away; it’s about the experience of Black people in America. The piece also struggles to get on its feet, for something is always deliberately preventing the music from moving forward — quizzical interruptions, nearly discordant comments from the brasses, short contrasting passages that have little to do with what came before or after them. Still’s note about the piece claims that the passage near the end represents “the triumph of the people,” but it seems to peter out inconclusively. This work is a portrait in sound of ingrained American racism that will never go away (alas), and as such it makes a thought-provoking impression. Still never forgot — nor flinched from — who he was and who he represented.

Payare brought out Dorothea Röschmann, every inch the experienced Wagnerian diva, to sing the five Wesendonck Lieder, two of which are warmup exercises for Acts 2 and 3 of Tristan und Isolde. The songs were originally written for piano and voice; Wagner only orchestrated the last one, “Träume” (Dreams), himself. Full orchestrations were done by conductor Felix Mottl. In this case, Payare urgently led a chamber-sized delegation from the Phil, on top of which Röschmann unleashed an Isolde-sized soprano with a wide vibrato and big crescendos. Both transformed the intimate musings of a lovestruck composer into large-scale music drama.

Brahms’s Symphony No. 1 can be one of the most consoling pieces in the repertoire, but for Payare it was a vehicle for extroverted, high-energy heroism. The first movement exposition theme and especially its repeat pounded away rhythmically, the music rising to an almost violent power at the climax. The extroversion continued through the second and third movements, and only at the beginning of the finale did the conductor relax enough to allow some mystery to seep through, before making a high-powered run for the finish line.

Payare was fun to watch, for sure — dancing around on the podium with occasional deep-knee crouches, whipping the orchestra on, and getting an orchestral response appropriate to all that athletic activity. He reminded me a little of the young Michael Tilson Thomas back in the day, when MTT was all motion and footwork while guest-conducting in L.A. There are, of course, other subtler roads to Brahms’s First, but if I were to introduce someone to Brahms for the first time, I would most likely choose Payare’s electrifying way.