Every two years, the Rubin Institute for Music Criticism convenes in San Francisco, teaching music students across the U.S. about music journalism. SF Classical Voice has partnered with the Rubin Institute to give the program’s top writers more experience in the field with an internship. This year’s Rubin winners, Emery Kerekes and Lev Mamuya, will be with SFCV for six months, reporting from New York and Boston, respectively.

New York City was abuzz with talk of Monochromatic Light (Afterlife) in the days leading up to its Sept. 28 opening at the Park Avenue Armory — and rightfully so. Commissioned for the 50th anniversary of Houston’s nondenominational Rothko Chapel (and the eponymous Morton Feldman piece from a year later), the work represented a rare confluence of artistic mediums nigh unseen since live performance returned.

Visionary composer Tyshawn Sorey laid a contemplative musical response to Feldman, newly expanded from the 50 minutes of DaCamera’s limited Houston premiere to a substantial hour and a half. Eight new paintings from preeminent abstractionist Julie Mehretu hung majestically in the Armory’s 55,000-square-foot drill hall, apt stand-ins for the moody black Rothkos of the Chapel. Reggie (Regg Roc) Gray, the pioneer of the Brooklyn-originated hybrid street dance flexn, contributed visceral choreography. The omnipresent Peter Sellars — perhaps the opera world’s most visible director — presided over the production.

Feldman’s Rothko Chapel is a work of muted sorrow — Mark Rothko, to whom the placid 25 minutes pay tribute, killed himself exactly 366 days before the Chapel’s opening in 1971. Those overcurrents of pain and anguish weave themselves through Monochromatic Light (Afterlife). 2022, the creative team agreed, is a ripe time to meditate on silent, deep mutual grief, between the pandemic, Black Lives Matter, Jan. 6, and more.

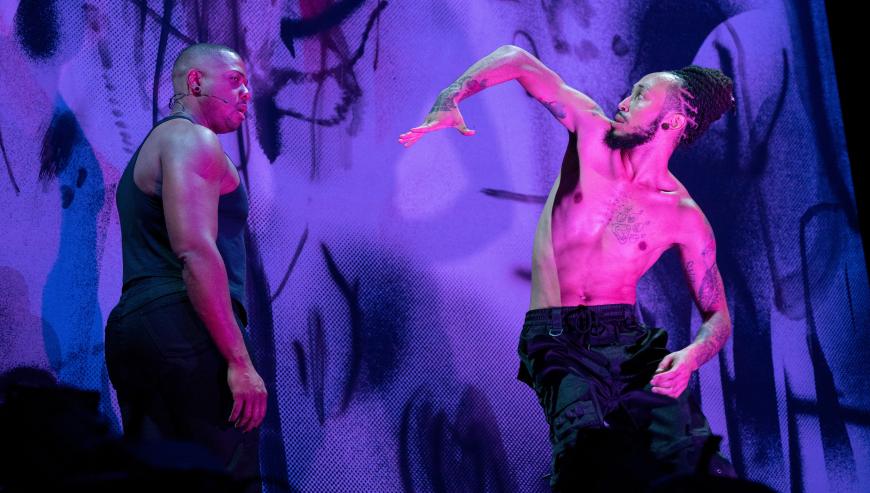

For 90 minutes, the performers mourned profoundly, unified not by a flashy spectacle or plot but by a somber feeling both intangible and unspoken. Sellars cast the grand, dignified work in a stadium octagon of sorts, with Mehretu’s evocative artworks delineating the sides. In front of each stood a dancer of Gray’s D.R.E.A.M. Ring collective, perched on an elevated platform. The audience sat in the center of the elevated installation, surrounding a low stage from which the evening’s instrumentalists played. Thus, it was impossible to see all eight dancers and paintings simultaneously — the work was, from any given vantage point, purposely, necessarily, and poignantly incomplete.

The three key instrumental performers reunited after a fabulous recording of Rothko Chapel for ECM Records in 2015. DaCamera Artistic Director Sarah Rothenberg reprised her role as celesta player, doubling here on a motivic piano part, Sorey’s one instrumental addition to Feldman’s original configuration. Stalwart avant-garde percussionist Steven Schick found infinite timbres in his modest setup; with yarn mallets on tubular bells, he created eerie backdrops to the sparse score. Viola soloist Kim Kashkashian completed the trio, her rich vibrato a stark contrast to the gossamer harmonics that dotted her part. The trio showed virtuosity in their calm, even keel as Sorey, the stage’s fourth inhabitant, conducted over their heads to a dim stall containing a ghostly Choir of Trinity Wall Street.

Baritone Davóne Tines commands any room, and this was no exception. He sang on slow, deliberate syllables lifted from the spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” as he paced the dancers’ octagonal catwalk with glacial consideration. His face stayed contorted into a woebegone sob as his upper register, gorgeous both in falsetto and full voice, rang across the cavernous room. The dancers paid him no heed as they moved isolated shoulders, wrists, and fingers with smooth, superhuman control. As they popped their shoulder blades, I squirmed — but that discomfort felt intentional and symbolic.

Mehretu’s artworks also served as projection surfaces for James Ingalls’s heathered lights, which highlighted the paintings’ coloristic layers in alternatim. In a work with so many individually moving parts, the rare instance of close coordination was cathartic.