It's been a long wait in San Francisco for a complete production of Les Troyens: 157 years since Hector Berlioz finished the score, more than 45 years since San Francisco Opera's first, heavily-cut performances, and nearly 15 years since Pamela Rosenberg promised us a staging.

And now David Gockley has finally brought Les Troyens to the War Memorial Opera House. Was it worth the wait? You bet it was. Majestically conducted, strongly cast, and presented in a handsome and sometimes spectacular production, Les Troyens stands in all its idiosyncratic glory as the grandest, and greatest, French grand opera of them all.

Based on selected episodes from Virgil's Aeneid, Les Troyens tells familiar stories from the Trojan Wars: how the Greeks conquered Troy after a 10-year siege by leaving a giant horse filled with warriors outside the city gates and how the Trojan hero Aeneas (here Enée) fell in love with Dido (Didon), queen of Carthage, only to abandon her so that he could fulfill his destiny by founding Rome and dying a hero's death on the battlefield. Berlioz worshipped Virgil and composed Les Troyens on an epic scale equal to his source material. The opera, in five acts, clocks in at about five hours, and requires 95 instrumentalists, 16 solo singers, 90 choristers, and, being French, a ballet troupe.

Mezzo-soprano Susan Graham and tenor Bryan Hymel lead the mostly-superb cast as Didon and Enée. The beauty and freshness of Graham’s voice belie her 25 years with the company, and she brought a regal depth and passion to her portrayal of the doomed Queen. Hymel, a 2001 Merola alumnus, made one of the most impressive debuts of recent years, singing with poise, heroic ring, easy control over a big, cool-toned tenor, and far and away the best French in the cast. They were a magnificent pair of lovers, breathtaking in their love duet “Nuit d’ivresse” and in each of their solos. Graham’s noble rage and despair in her death scene, especially, were the stuff of legends.

Cassandre, daughter of King Priam, dominates the first two acts of Les Troyens, first with her fruitless warnings that doom awaits the Trojans, then, after the Greeks emerge and conquer the city, by leading the surviving Trojan women in a mass suicide to avoid rape and capture. Anna Caterina Antonacci, returning to the company after a 17-year-absence, plays the prophetess with gripping physical intensity, whether writhing on the ground or begging her beloved Chorèbe (Brian Mulligan) to leave the city lest he die. But alone among the principal singers, Antonacci disappointingly failed to project her voice across the footlights, sounding too small-voiced and distant for such a large house; as well, her voice was best at full cry at the top of her range, but lacked heft in the critical lower register where most of the role lies.

For this production, there’s luxury casting of headline stars in several of the smaller roles. The versatile Brian Mulligan is a noble and tender Chorèbe. The always-lovely Sasha Cooke sang Anna, sister of Didon, who unknowingly sets the tragedy in motion by teasing the widowed Queen into considering the possibility of new love. Cooke’s voice is cut from nearly the same cloth as Graham’s, making it easy to believe that they’re sisters. Rossini tenor René Barbera is Iopas, and floats his serenade “O blonde Ceres” with easy skill.

Christian Van Horn is, as expected, a strong Narbal. Adler Fellow Chong Wang brings an exceptionally beautiful lyric tenor to Hylas and his nostalgic aria “Vallon sonore.” As Ascagne, Enée’s young son, Adler Fellow Nian Wang was adorably boyish and sang with a lovely, light mezzo. Buffy Baggott made a strong physical impression as Queen Hécube, who is hardly heard but mostly seen in attendance on Philip Skinner’s King Priam. Dancer Brook Broughton played the mute role of Andromache with grave dignity, holding every eye during her short scene of tribute to the Trojan dead. Philip Horst, William O’Neill, and Jere Torkelsen ably filled their small roles. And as a pair of Trojan sentries who really don’t want to leave Carthage, Adler Fellows Matthew Stump and Anthony Reed charmed in the only moment of levity in the work as bored and gossiping sentries.

The new staging, by David McVicar, is a co-production with the Royal Opera, La Scala, and the Vienna State Opera, and it has already been seen in London and Milan. The production uses a gigantic, multilevel unit set designed by Es Devlin, whose convex side, tricked out like the dark sides of an iron-plated, 19th-century battleship, stands for Troy. It looms grimly over the stage, surrounded by piles of rubble, then divides in half and swings open to make space for the central ceremonial scenes and the eventual appearance of the Trojan horse.

Therein lies one of the production’s theatrical coups, as the horse, towering above the Trojans, looks like a cross between a Louise Nevelson sculpture and something you’d see at Burning Man. It is so big, and so scary, that you can easily imagine it bearing a battalion of Greeks.

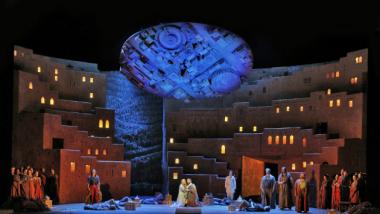

For the Carthage scenes, the set is swung around 180 degrees and presents its concave side, a sort of North African pueblo, sand-colored and with doors and windows and decorations stacked up atop one another. The lighting, by Pia Virolainen and original lighting designer Wolfgang Göbbel, changes radically, along with the mood of the piece, from the Trojans’ doom-laden end to sunny rejoicing over Queen Didon. The Trojan scenes’ costumes also draw on mid-19th-century clothes, while the Carthaginians dress in loose outfits based on Libyan patterns and cloth. Moritz Junge designed the costumes.

By and large, the set works quite well, the exception being the inexplicable decision to plant a miniature city of Carthage right in the center of the stage. Some of the action takes place on the circular pedestal holding the city, and the singers have to carefully pick their way across it to avoid injury. It’s also used for the acrobatic display that stands in for one of the intended ballet sequences. During the course of the later scenes, the pedestal rotates above the stage and eventually splits in two, presumably representing the disintegration of the happy world of Carthage. [Donald Runnicles] paced the opera so well and had such command of the work's monumental proportions that it seemed the shortest five-hour opera ever.

To Donald Runnicles, former music director of S.F..Opera, must go a great deal of the credit for this production's magnificent success. He led the sprawling score with tremendous authority, a sure hand for orchestral balance and sonority, and poetic sensibility at the score's most desperate, and most tender, moments. He paced the opera so well and had such command of the work's monumental proportions that it seemed the shortest five-hour opera ever.

The opera orchestra played the music as though they were born to it, though I can't imagine many of the musicians have played this great rarity before. The brass were especially splendid in their Wagnerian might and numbers. In the Royal Hunt and Storm, the short tone poem that opens Act IV, acting co-principal horn Christopher Cooper and extra horn Eric Achen played with magical beauty from the Grand Tier. Principal clarinet Jose Gonzalez Granero was in magnificent form throughout the opera, whether playing solo or in filigreed counterpoint to the singers.

Ian Robertson's Opera Chorus, in superb collective voice, made its own huge contribution to the success of the opera. The chorus has about two hours of singing, more than any of the principal singers. Their music sets the stage and moves the action along as much as any of the principals, from the opening chorus of rejoicing, when the Greeks' siege of Troy has apparently been lifted, to the processional “Gloire à Didon,” in which the Carthaginians express their love for their queen.