Julia Wolfe’s Her Story (2022), written in honor of the long fight for women’s suffrage, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade might not be the most obvious pairing for an orchestra concert, but on different levels, they’re both about the ongoing struggle of women in male-dominated societies. In the case of Scheherazade, the titular character is fighting for her very life by trying to fascinate her husband sufficiently so that he won’t kill her. Her Story takes a broad historical view of women in the United States.

The San Francisco Symphony, a co-commissioner of Her Story, performed both works on Thursday, May 25 under conductor Giancarlo Guerrero. The Nashville Symphony, where Guerrero is music director, is another commissioner, and as the composer mentioned in brief remarks before the concert, Her Story was very much built in collaboration with Guerrero and his orchestra. Performances of Her Story require that the presenting orchestra use the production managed by Wolfe’s new-music group Bang on a Can, and they must be approved by the composer.

Her Story lasts about 40 minutes, and it’s written for a large orchestra and an amplified chorus of 10 women’s voices, here Lorelei Ensemble. The program notes characterize Her Story as an oratorio, but unlike the well-known oratorios of Handel and Haydn, it tells its story allusively and elliptically, rather than as a direct narrative. Wolfe created the lyrics from the letters of Abigail Adams, a founding mother of the United States; the words of anti-suffragists; and Sojourner Truth’s famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech.

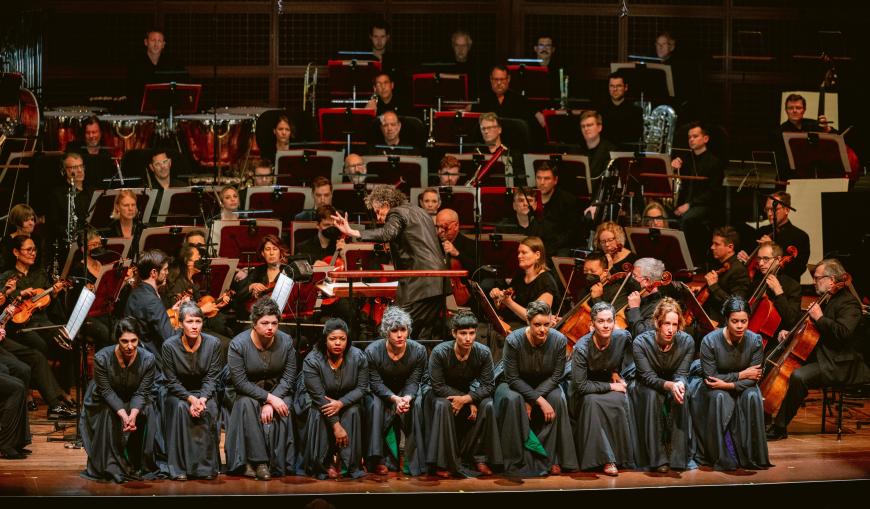

The lyrics total 137 words, including “Foment” and “Raise,” the titles of the oratorio’s two sections. That’s not much text to work with over 40 minutes, and there’s a lot of repetition, in keeping with the minimalist musical style of the composition. The overall presentation of Her Story is both theatrical and ritualistic. The choristers wear identical gray-black floor-length dresses and single red gloves. They gesture and move about the performance space largely in unison, starting in the terrace behind the orchestra and eventually coming down to orchestra level.

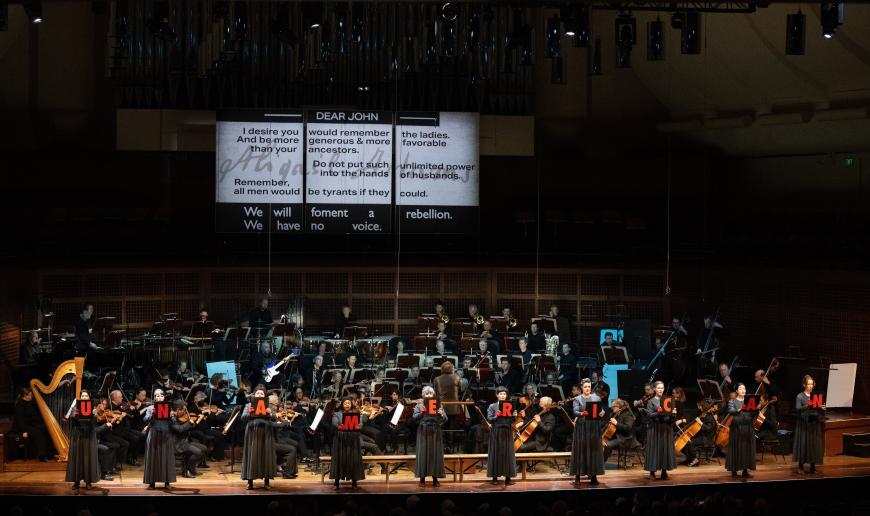

The Adams text, drawn from one of Abigail’s letters to her husband John, reminds the future president that in drafting the nation’s founding documents, he should remember women and limit the power of men over them. She also threatens a rebellion by women. The text is broken down into fragments, emerging word by word and phrase by phrase. Sometimes the words are sung; sometimes they’re whispered. The text of the letter is displayed across banners at the back of the terrace.

For “Raise,” the chorus leaves the terrace for the stage; the orchestra and singers are lit with an eerie green. The text consists of epithets that anti-suffragists hurled at proponents of votes for women (and that some continue to use against proponents of women’s rights to this day), including “Unloving, Unstable, Unruly … Unglued … Bolshevik, Communist, Anarchist … Emotional, Hysterical, Socialist, Impossible.” During this passage, the singers hold up signs with the words they’re singing and eventually open their music folders to display the individual red letters making up the word “UNAMERICAN.” By then, the lighting has shifted to blue.

The singers move to a bench at the front of the stage, where you can see that their dresses have colorful linings in green, red, and purple. They remove their gloves. They turn on the bench to face one side of the hall and then release the bodices of each other’s dresses, revealing black or white tank tops underneath. They stand, and at one point, they turn their backs to the audience.

Musically, Her Story feels like an angry, unrelenting work. Its music moves in gigantic blocks of sound, with a slow harmonic rhythm. From row J, it was often very, very loud. You couldn’t easily pick out individual instruments or their solos. Lorelei Ensemble sang with precision, spirit, and good enunciation; amplification was absolutely necessary given the sonic welter, but one could still regret the flattening effects of that amplification.

As a whole, Her Story lacks contrast and variety. The relentlessness must be a deliberate choice, but it makes the work wearing to hear. Wolfe’s earlier oratorio, Anthracite Fields (2014), traverses a wider musical space while using some of the same compositional techniques. As theater, Her Story is uncomplicated and direct. As a political statement, it’s a passionate reminder that a century after American women won the right to vote, some on the political scene have endorsed organizations that talk about taking that right away, along with women’s bodily autonomy and the rights of LGBTQ people.

The concert opened with a glorious account of Scheherazade, showing off the work’s luscious orchestration and making its narrative quite clear. Assistant concertmaster Wyatt Underhill brought delicacy and romantic flair to the violin solos that represent Scheherazade. Harpist Meredith Clark joined him with liquid command in those passages. Flutist Jessica Sindell, clarinetist Matthew Griffith, and oboist James Button all contributed atmospheric solos. Guerrero conducted the entire concert enthusiastically and with a fine ear for the shape, colors, and balances of Rimsky-Korsakov. I wish that Her Story had had more of that balance.