I felt fortunate to witness the excitingly virtuosic multicultural concert by the Silkroad Ensemble at Stanford’s Bing Concert Hall last November. Imagine my anticipation in hearing that three members of the ensemble would perform for the first time as a trio under the aegis of Noe Music on Sunday, Jan. 14.

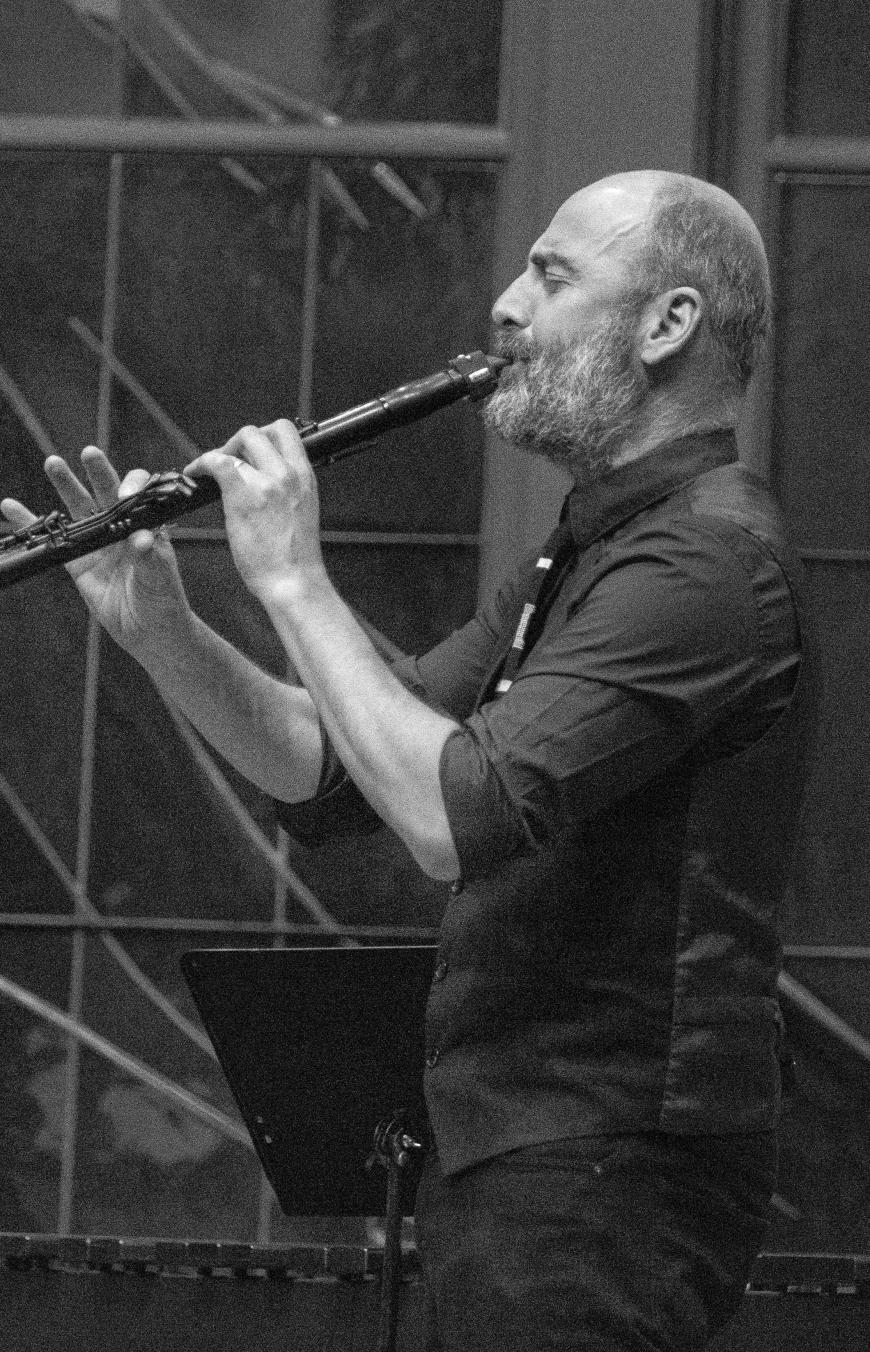

The 220-seat Noe Valley Ministry made for a more intimate but equally delightful experience. Most of the compositions and arrangements on the program were by the three featured instrumentalists: clarinetist Kinan Azmeh, marimbist and percussionist Haruka Fujii, and cellist Karen Ouzounian.

Fujii’s bells paired with Ouzounian’s cello on the opening “Some Games Played Over Thousands of Miles,” which, as the title might suggest, the two co-composed during the pandemic. Azmeh’s Syrian Imaginary Dances followed, evoking a pair of cities in his native Syria. As in much of the program’s music, he channeled regional folk influences, sounding a wavering drone on clarinet against Ouzounian’s pulsing pizzicato on the tonic, later ascending in a slow crescendo toward the top of his register. Fujii, on her 5⅓-octave Korogi marimba, intoned alluring open fourths and fifths.

A series of trio and solo settings incorporated input from other composers. “Sari Sirun Yar” was composed by Armenian musician Gusan Ashot and arranged for solo cello by Ouzounian’s husband Lembit Beecher. The piece was indeed folksy and lively, making lovingly full use of her instrument, with slurs, simultaneous pizzicato and bowing, and col legno. In similar fashion, Azmeh showcased the clarinet’s dynamics, range, and trills on Prayer, a tribute to the Palestinian American academic Edward Said. Fujii dedicated her solo marimba performance of Land, by Japanese composer Takatsugu Muramatsu, to victims of the 7.6-magnitude earthquake three weeks ago on Japan’s west coast. The piece took the form of a lovely air with affecting modulations, somewhat evocative of Celtic harp.

The first two sections of Suite of Armenian Dreams were also composed by deceased Armenians and arranged by Ouzounian, who noted that her family has roots in Anatolia but migrated to Syria and Lebanon. “Groong,” by priest, teacher, musician, and ethnomusicologist Komitas, was written for voice and piano but shared here by all members of the trio. “Mardigi Yerke,” by Ashot Satyan, an evocation of a soldier’s longing for home, had cantabile clarinet accompanied guitar-like by pizzicato cello. This was one of the only points in the program where the two instruments harmonized in chords. “Der Zor,” about a settlement in Syria, was sourced in an early recording by an Armenian expatriate in Fresno. It had Fujii beating out a dance rhythm on the Irish bodhrán drum. “Groove” was an Ouzounian original, showcasing folksy fragments and more of her pizzicato perkiness.

The backstory Azmeh shared about his composition The Fence, the Rooftop, and the Distant Sea sounded timely and appealing. Strife in Syria had relocated him to Lebanon in 2016, where seeking homeland led him and other expatriates to visualize details in memory. The “Prologue” to this process was invoked as shimmering high harmonics on cello. Allusions to Middle Eastern modes in “Ammonite” were agitated by furtive fast triplets and quirky close intervals. The “Monologue” had the cello sobbing, growling, sliding. Ouzounian’s powerful bowing and dazzling panoply of extended techniques were in full force here and on the following “Dance,” energetic but replete with angst. The suite affectingly and thoughtfully resolved into benign nostalgia in the “Epilogue.”

Fujii announced herself as new to composition as she introduced her Divisions and invited Noe Music’s wife-and-husband co-artistic directors, violist Meena Bhasin and violinist Owen Dalby, to join the trio onstage. The three-part piece imported traditional Japanese musical elements, pairing the marimba prettily with Ouzounian’s cello and Bhasin’s alluring viola before activating some joyful presto cacophony.

The program concluded with Azmeh’s celebratory “Wedding,” which had me remembering my own marriage in that very same space almost three dozen years ago. This is part of the clarinetist’s three-movement Suite for Improvisor and Orchestra, and the composer illustrated the scene of a traditional Syrian wedding in a public square, where musicians perform in accordance with their mood and their state of inebriation. Violin and viola added color and zest to what developed as a delirious dance in 7/4 time, the clarinet sounding Syrian modes evocative of klezmer music. Fujii deployed both bodhrán and tupan, a two-sided Bulgarian folk drum. The surprise sudden ending drew a clamorous response from the crowd, followed by a standing ovation. “I’m hoping someone in Gaza or Yemen will feel this, too,” said Azmeh.

In the audience sharing the spirit was Karen Heather, founder of the original Noe Valley Chamber Music series in 1992. She was recognized by Dalby, who also praised the trio, saying, “I have not yet metabolized the depth that these three musicians bring. It has been a dark time, and what they are doing is bringing us hope.”