I woke up on Sunday, Feb. 11 with a short, punchy musical motif running through my head. If you’d been at the contemporary-music group Wild Up’s program at Bing Concert Hall the night before, this might have happened to you, too.

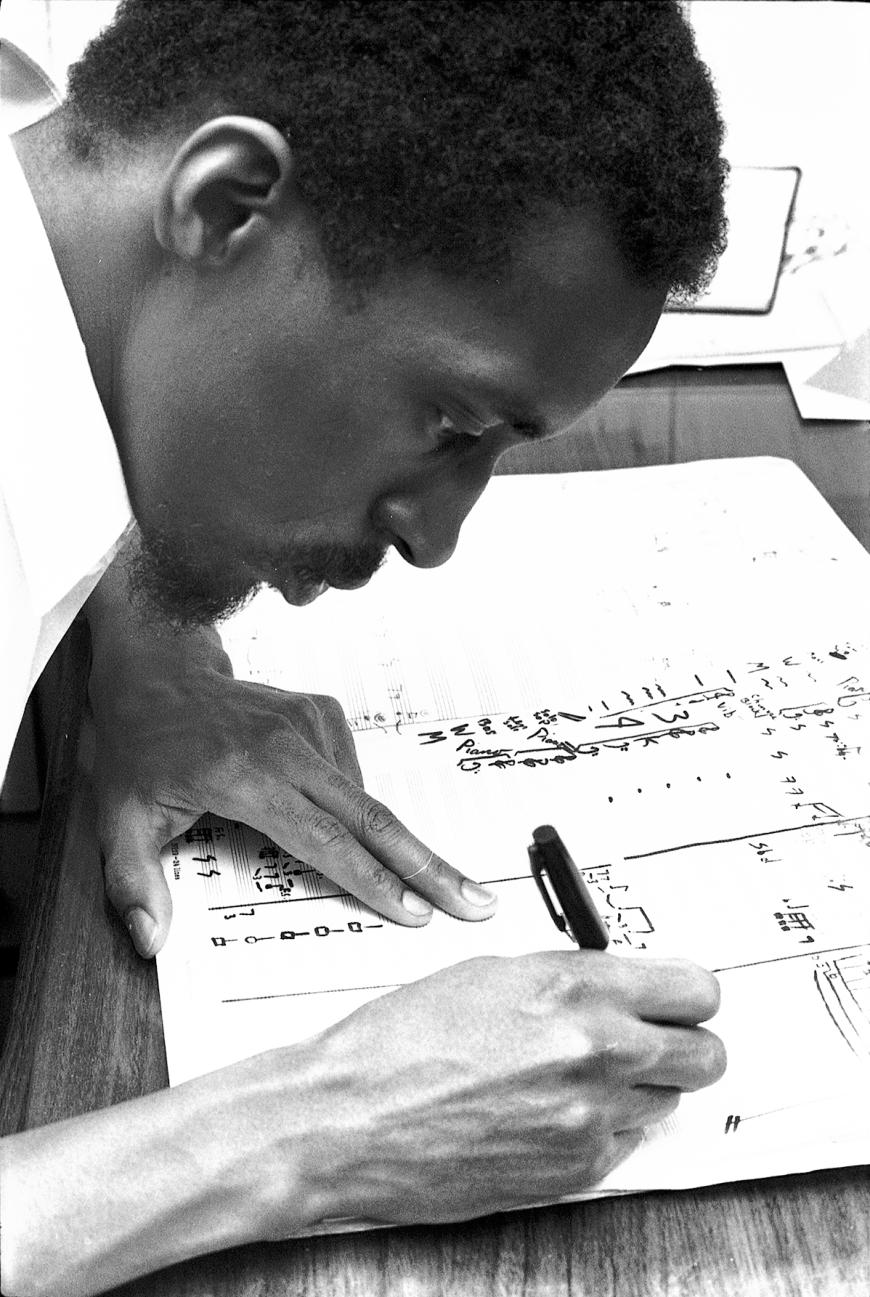

That’s because the motif is a constant in the composer Julius Eastman’s Femenine (1974). It appears in every measure, in every moment of the piece, which lasts around an hour and a quarter. The score of Femenine is just five pages long. It’s sparsely notated, and as a result, every performance is different.

How can this be? To start with, the score allows for varied instrumentation. The printed music says it’s for winds, marimba/vibraphone, sleigh bells, piano, and bass. For Saturday’s performance, there were two violins, cello, bass, electric guitar, piano/keyboard, marimba/vibraphone, flute/piccolo, bassoon, several saxophones (one doubling clarinet), and two singers.

Wild Up staged the performance in a stylized, ritualistic fashion. Musicians scattered around Bing played the sleigh bells, which open the work, and kept them going throughout. One of these was conductor Christopher Rountree, who said after the performance that he played only through the 51st minute because he had to start giving cues in minute 52. He didn’t give that many cues — and apparently only to coordinate a major shift.

Percussionist Sidney Hopson entered the stage playing sleigh bells and then took up his spot with the mallet instruments and started playing that constant motif. The other musicians arrived onstage at intervals, picking up their instruments and joining in. The motif moved throughout the ensemble, sometimes louder, sometimes softer. The score allows for some improvisation as well, and as far I could tell, each musician went off score at times. Rountree mentioned that pianist Richard Valitutto was never actually playing what’s in the score.

Over the course of the performance, individual musicians would leave the stage and come back a few minutes later. These comings and goings were cued and timed to events in the score, which includes durations for each section.

Femenine is far more than one motif. Others include a hymn tune and at least one set of blocky chords. Different instruments or choirs of instruments come to the fore. Sometimes a motif is played by two groups of instruments but slightly out of phase with each other. The singers wail and whoop motifs that aren’t notated in the score. At a couple of points, you hear a passage that sounds like John Adams’s Nixon in China, when the president’s plane is about to land in Beijing, though Femenine dates from more than a decade earlier than the opera.

At the end of the performance, the players walked offstage one by one, reversing the opening, with Hopson the last to leave. The sleigh bells continued and then died away.

Femenine is built from uncomplicated materials, but the repetition, recombination, and overlapping builds a dense and complex structure over the course of a performance. That structure can’t be absorbed in a single hearing, or maybe even 10 hearings, particularly given the improvisatory aspects of the work. The incantatory repetitions mesmerize the listener; this is one work that can, and perhaps should, be experienced by letting it wash over you.

The members of Wild Up played with astounding musical unanimity, as if they were one giant instrument with one beating heart. They were amplified, and in the resonance of Bing, this created a wall of sound through which you could not always make out the individual instruments and musical themes. An unamplified performance, or one with fewer instruments, would be fascinating to hear.

On Feb. 9, Wild Up and a group of Stanford University students who had been working with the ensemble presented three of Eastman’s other works at Bing: Joy Boy, Gay Guerrilla, and Buddha. Like Femenine, these pieces are open-ended and enigmatic, allowing for various instrumentations and interpretations. The physical score of Buddha consists of a single page of manuscript paper with an egg-shaped drawing encompassing each line of musical notation. The score of Joy Boy is just one page, on which Eastman wrote “create ticker tape music.” Gay Guerrilla, scored for four equal instruments (usually four pianos or mallet instruments), has the longest manuscript.

Friday’s performance took advantage of the latitude granted by the scores, adding the student musicians to the larger forces of Wild Up for maximalist instrumentation of minimalist music. The three works have quite different feels because of their differing musical materials, but they all share a sense of organic growth and change, of performers coming together to connect with each other and the music.

The works felt lighter and perhaps more joyous than Femenine, possibly because of their length, possibly because they were new to the student performers. At the end of Gay Guerrilla, there was an extraordinarily long silence before the applause, as if the music continued to resound and develop in the silence, so deep was the impact on the listeners.

If you missed these performances, Wild Up will be presenting Femenine again on March 9 at Cal Performances in Berkeley. The group will be at Zellerbach Playhouse, a different space from Bing, and there will be some changes in the lineup of musicians. It’ll be different from the Stanford Live performance, and that’s very much in the Eastman spirit.